Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(2):553-565. doi:10.7150/ijbs.123740 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Disrupted astrocyte-neuron glutamine-glutamate cycling in the medial prefrontal cortex contributes to depression-like behaviors

1. Department of Anatomy and Convergence Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Institute of Medical Science, Tyrosine Peptide Multiuse Research Group, Anti-aging Bio Cell Factory Regional Leading Research Center, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, 52727, Republic of Korea.

2. College of Pharmacy and Research Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, 52828, Republic of Korea.

3. Department of Physiology and Convergence Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Institute of Medical Science, Tyrosine Peptide Multiuse Research Group, Gyeongsang National University, Jinju, 52727, Republic of Korea.

4. Department of Medical Science, College of Medicine, Catholic Kwandong University, Incheon 22711, Republic of Korea.

Received 2025-8-14; Accepted 2025-11-20; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

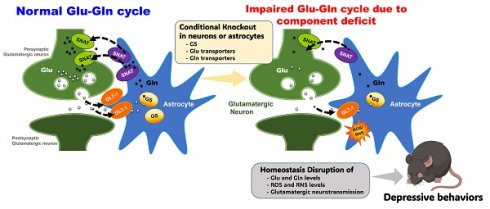

The regulation of the homeostasis of the glutamate (Glu)-glutamine (Gln) cycle within the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) has garnered substantial interest due to its essential role in maintaining normal emotional behaviors. Chronic stress possesses the potential to disrupt the homeostasis of the Glu-Gln cycle, thereby facilitating the onset of depressive behaviors. Nevertheless, the specific roles of individual components within the Glu-Gln cycle in relation to depression-related behaviors remain incompletely understood. This study aims to elucidate the specific roles of each component by implementing a cell- and region-specific conditional knockout (cKO) strategy. To achieve this goal, the genes encoding glutamine synthetase (GS), glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1), and sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporters, SNAT-3 and SNAT-5, were selectively ablated within astrocytes. In addition, the genes encoding SNAT-1 and SNAT-2 were specifically eliminated from glutamatergic neurons. A depressive phenotype was observed in the GS and GLT-1 cKO mice, correlated with increased levels of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) within the mPFC, whereas a reduction in Glu-Gln concentrations was uniquely identified in the GS cKO mice. Conversely, mice with cKO for SNAT-1, SNAT-2, SNAT-3, or SNAT-5 neither exhibited observable depressive-like behaviors nor reduced Glu-Gln levels. However, the simultaneous inactivation of either SNAT-1/SNAT-2 or SNAT-3/SNAT-5 induced depressive-like behaviors and reduced Glu-Gln levels. No systemic stress response or inflammatory manifestations were detected in any of the cKO mice. Furthermore, administration of Gln, acknowledged for its antidepressant properties, to GS cKO mice led to the amelioration of both depressive-like behaviors and Glu-Gln concentrations. These findings elucidate distinct and synergistic roles for the components involved in the Glu-Gln cycle in upholding appropriate Glu-Gln levels and mitigating ROS/RNS within the mPFC. Additionally, our cKO mouse models prove to be valuable tools in researching depression, which may aid in the development of new antidepressant treatments.

Keywords: glutamate-glutamine cycle, emotional behavior, glutamatergic homeostasis, depression, depression animal model, cell-specific conditional knockout

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) represents a prevalent yet severe psychiatric condition [1]. Manifesting in about 6% of the adult population on an annual basis [2], MDD has a high risk of leading to suicide, with individuals diagnosed with MDD exhibiting a suicide risk approximately 20 times greater than that of the general population [3]. Aside from the high risk of suicide, it is particularly concerning that MDD was identified as the second leading cause of years lived with disability (YLD) and accounted for the largest share of mental YLDs in 2021. Furthermore, from 2010 to 2021, the 'age-standardized disability-adjusted life-years' for MDD increased by 16.4% [4]. Therefore, it is crucial to develop innovative antidepressant treatments that are based on a thorough understanding of its etiological mechanisms.

Recently, the glutamate (Glu) hypothesis has garnered significant attention to elucidate the mechanisms of MDD. The hypothesis posits that diminished glutamatergic activity within the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) directly influences depressive behaviors, substantiated by evidence derived from both preclinical and clinical investigations. Notably, reductions in the quantity of astrocytes and the concentrations of Glu and glutamine (Gln) have been observed in patients exhibiting suicidal tendencies or depression [4-6]. The activity within the mPFC of individuals diagnosed with depression was diminished, and the volume of this region was likewise reduced [7, 8]. Additionally, both the antidepressant esketamine and the dextromethorphan-bupropion combination, approved by the US FDA, function through a shared mechanism that involves the activation of glutamatergic signaling in the prefrontal cortex [9-11].

The concentrations of Glu-Gln and the glutamatergic activity predominantly rely on the Glu-Gln cycle, which is sustained between glutamatergic neurons and astrocytes [11, 12]. Glutamatergic neurons release Glu for neurotransmission. After signaling, astrocytes reuptake Glu via glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1) [13]. Within the astrocyte, glutamine synthetase (GS) transforms Glu into Gln. Gln is then conveyed to presynaptic glutamatergic neurons through sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporters (SNAT)-3 and -5 in astrocytes and SNAT-1 and -2 in neurons. Finally, Gln is reconverted into Glu by glutaminase for subsequent signaling. (Fig. S1A). Disturbance in the Glu-Gln cycle has been demonstrated to induce depressive behaviors in rodent models [14-17]. Supplementation with Gln rescues the deficits of Glu-Gln, thereby enhancing glutamatergic neurotransmission and demonstrating anti-depressive effects in a chronic immobilization stress (CIS)-induced depression mouse model [18]. Furthermore, recent findings propose that activating GS compromised by CIS may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for depression [19].

Numerous studies have suggested the critical importance of homeostasis in the Glu-Gln cycle to preserve emotionally healthy behaviors, as well as elucidating the role of each key component within the Glu-Gln cycle to comprehend the underlying etiological mechanisms of MDD. From these considerations, this study employed a cell-specific CRISPR/CAS9 system to selectively suppress the expression of principal proteins, including GS, GLT-1, SNAT-1, SNAT-2, SNAT-3, and SNAT-5, within the mPFC, followed by an evaluation of the behavioral outcomes resulting from the conditional knockout (cKO) of each gene (Fig. S1B). Additionally, through biochemical analysis of stress biomarkers and amino acids, the impact of each protein cKO was investigated. Consequently, the study confirmed the role of each protein in normal behavioral manifestations and identified crucial etiological alterations within the mPFC that may lead to depressive behaviors, information that holds significant implications for the diagnosis of MDD and the development of novel antidepressants.

Materials and Methods

Small guide RNA (sgRNA) and adeno-associated virus (AAV)

For cloning sgRNA, we first generated the AAV viral vector of serotype 2, called pX552ch, by replacing the coding sequence (CDS) of EGFP of pX552 (Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA) with the CDS of mCherry. Various sgRNA sequences were subsequently subcloned into the sgRNA replacement site of pX552ch by using the HiFi assembly method (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA), and the resulting plasmid were verified by sequencing. Sequences and vector map are summarized in Supplement information (Fig. S2 and Table S1). Using the constructed vector, serotype 2 AAV particles were produced at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology.

Animals

We purchased a male and female pair of Vglut2-IRES-Cre (Stock No: 016963) and Rosa26-LSL-Cas9 knockin (Stock No: 026175, CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP) mouse from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). By breeding the Vglut2-Cre and the CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice, the Vglut2-IRES-Cre::CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mouse line was prepared. For glutamatergic neuron-specific cKO, AAV2-px552ch-sgSlc38a1and/or Slc38a2 were delivered into prelimbic cortex (anteroposterior +1.5, mediolateral ±0.3 and dorsoventral -2.5 mm) via stereotaxic surgery of Vglut2-IRES-Cre::CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice. For astrocyte specific cKO, CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice were injected with pAAV.GFAP.Cre.WPRE.hGH to enable astrocyte-specific activity of the sgRNA. In Vglut2-IRES-Cre::CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice, EGFP was observed throughout the brain sections, including the prelimbic cortex (Fig. S1C). In contrast, in CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice, EGFP was observed only in the virus-injected region (Fig. S1D). The mice were treated by the protocol of the Institute Animal Care and Use Committee of Gyeongsang National University (approval No. GNU-190325-M0019).

Behavioral tests

Two weeks after stereotaxic surgery, the behavioral tests, including open field test (OFT), tail suspension test (TST) and sucrose preference test (SPT), were conducted as previously described [17]. The mice movement was tracked using EthoVision XT software (Noldus, Wageningen, Netherlands).

Blood and tissue sampling

Mice were CO2 gas-anesthetized and their blood and mPFC of brain were collected between 9 to 11 am. Plasma was isolated using K3EDTA vacutainer by centrifuging at 4 ºC. The PFC samples were homogenized in RIPA buffer by glass beads using Bullet Blender Tissue Homogenizer (Next Advance, Troy, NY, USA). The resultant lysates were collected by centrifugation and stored at -80 ºC until use.

Corticosterone (CORT) and ROS/RNS measurement

Levels of corticosterone and ROS/RNS were quantified using Corticosterone ELISA Kit (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and OxiSelect™ In vitro ROS/RNS Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the protocol provided from the manufacturers.

Amino acid analysis

In plasma and mPFC, amino acids (Glu, Gln and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)) were measured using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry as described in the previous study [17]. Briefly, lysates and plasma were centrifuged, mixed with an internal standard (L-Glu-d5), and analyzed using an Agilent 6460 system (Agilent, Singapore) with a SeQuant ZIC®-HILIC column (2.1×100 mm, 3.5 μm, 100 Å). Separation was achieved with a gradient of 0.1% formic acid in water and acetonitrile, and detection of Glu, Gln, and GABA was performed in multiple reaction monitoring detection method.

Immunohistochemistry

After cardiac perfusion, the brain was sectioned to a 40 μm thickness by a vibratome (VT1200, Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany). The selected sections were blocked with 3% BSA in 1× phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween®20. Tissues were sequentially reacted to primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 594- or Alexa Fluor 680-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The fluorescent image was obtained using a confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The antibody information is as follows: GS (MAB302, Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA), GLT-1 (AB1783, Merck Millipore), SNAT-1 (12039-1-AP, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA), SNAT-2 (sc-514037, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), SNAT-3 (14315-1-AP, Proteintech), and SNAT-5 (ab72717, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

Western blot analysis

After SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), the separated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The membrane was then blocked in 5% skim milk (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), followed by incubation with primary antibodies: GluA1 (MA5-27694, ThermoFisher Scientific), GluA2 (32-0300, ThermoFisher Scientific), GluN2A (sc-390094, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), GluN2B (sc-365597, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and β-actin (MA1-140, ThermoFisher Scientific) and subsequently with goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (31430, ThermoFisher Scientific). The membrane was then reacted with Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific). Images were obtained using an iBright™ CL1500 Image System (ThermoFisher Scientific) and analyzed using iBright Analysis Software (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current measurement

Measurement of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSC) in the mPFC was conducted as described in a previous study [19]. The brain slice including prelimbic cortex area was carefully placed on a recording chamber superfused with artificial cerebrospinal fluid. To remove GABAergic currents, 100 μM picrotoxin or 10 μM 6-cyano-7-nitroqui-noxaline-2,3-dione and 50 μM D-amino-phosphovaleric acid were treated. The pipette solution was composed of 130 mM KCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM MgATP, 0.5 mM Na2GTP, and 5 mM phosphocreatine. The currents were recorded from glutamatergic neurons with EGFP (holding potential was -70 mV) using a MultiClamp 700B Amplifier (Molecular Devices) in the whole-cell configuration, and analyzed by Clampfit (Ver. 11.1, Molecular Devices) and MiniAnalysis (Ver. 6, Synaptosoft, Fort Lee, NJ, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data were represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc test or Student′s t-test (p < 0.05) using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

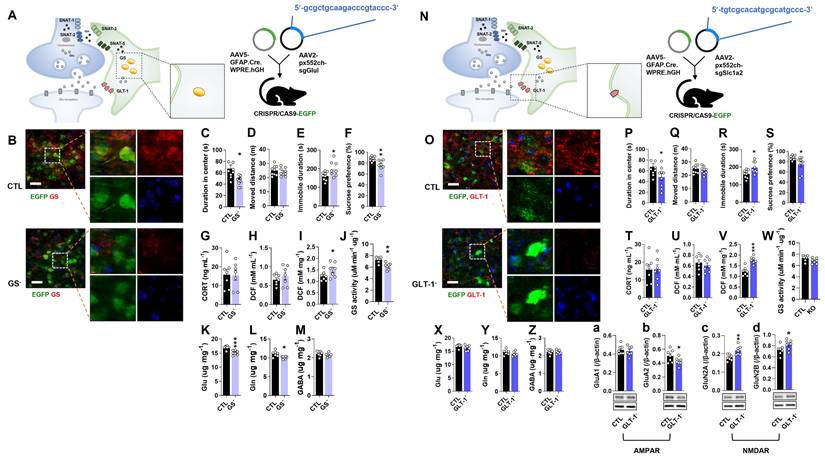

Astrocyte-specific GS knockout (GS cKO) causes depressive-like behaviors with the reduction of Glu and Gln levels

To investigate the role of astrocytic GS in depression, GS cKO (GS-) mice were generated by co-injecting pAAV.GFAP.Cre.WPRE.hGH and pAAV2.pX552ch-sgGlul into CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice (Fig. 1A). Efficient GS knockout was confirmed by a marked reduction in GS immunoreactivity compared to the pAAV.GFAP.Cre.WPRE.hGH-injected group (CTL group) (Fig. 1B). Consistent with the hypothesis that GS dysfunction in astrocytes impairs glutamatergic homeostasis and induces depression-like phenotypes, GS cKO mice exhibited significant anxiety, helplessness, and anhedonia in the OFT, TST, and SPT, respectively (Fig. 1C-F). To assess if these behavioral abnormalities were linked with baseline levels of stress-sensitive marker expression, measurements of plasma corticosterone (CORT) and ROS/RNS levels were conducted. The deletion of GS did not lead to significant changes in either corticosterone or peripheral ROS/RNS levels (Fig. 1G, H). However, ROS/RNS levels in the mPFC were markedly increased (Fig. 1I). Furthermore, GS activity and the levels of Glu and Gln were significantly decreased in the mPFC of GS cKO mice, while GABA was not changed (Fig. 1J-M). These findings indicate that astrocytic GS dysfunction disrupts the Glu-Gln cycle and selectively elevates oxidative stress in the mPFC, which may underlie the observed depressive-like behaviors.

Changes of phenotype in glutamine synthetase and glutamate transporter-1 (GLT-1) conditional knockout (cKO) mouse (GS- and GLT-1-). (A and N) Experimental scheme. The dotted and solid boxes indicate the target proteins of cKO and the expected changes, respectively. The two viruses for Cre recombinase and small guide RNA (sgRNA) were injected into the prelimbic cortex of CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice. The blue sequences indicate the sgRNA nucleotide sequences. (B and O) EGFP (green), GS or GLT-1 (red) signals in the prelimbic cortex. Blue signals are DAPI. Scale bars = 50 μm. (C and D, P and Q) Duration in center (C, t=3.151, df=16, p=0.006; P, t=2.126, df=16, p=0.049) and moved distance measured in open field test. (E and R) Immobile duration measured in tail suspension test (E, t=2.479, df=15, p=0.026; R, t=2.784, df=16, p=0.013). (F and S) Sucrose preference measured in sucrose preference test (F, t=3.298, df=15, p=0.005; S, t=2.348, df=15, p=0.033). (G and T) Plasma corticosterone (CORT) level. (H and I, U and V) Reactive oxygen/nitrogen species level in the plasma and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC, I, t=1.941, df=12, p=0.038; V, t=5.400, df=12, p<0.001). DCF, 2', 7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein. (J and W) GS activity in the mPFC (J, t=3.962, df=12, p=0.002). (K-M, X-Z) Glutamate, glutamine, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels in mPFC (K-M, Glu, t=4.817, df=12, p<0.001; Gln, t=3.053, df=12, p=0.010). (a-d) Expression of GluA1 and GluA2 (b, t=1.959, df=12, p=0.037), subunits of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor, GluN2A (c, t=3.509, df=12, p=0.002) and GluN2B (d, t=2.045, df=12, p=0.032), subunits of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor in the mPFC of GLT-1 cKO mice. All data were represented as mean ± SEM and statistically analyzed by unpaired, two-tailed t-test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001).

Astrocyte-specific GLT-1 cKO causes depressive-like behaviors without changes in Glu and Gln levels

To examine the role of astrocytic GLT-1 in depression, GLT-1 cKO (GLT-1-) mice were generated by co-injecting pAAV.GFAP.Cre.WPRE.hGH and pAAV2.pX552ch-sgSlc1a2 into CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice (Fig. 1N). GLT-1 immunoreactivity was markedly reduced compared with controls (Fig. 1O). GLT-1 cKO mice displayed anxiety, helplessness, and anhedonia in the OFT, TST, and SPT, respectively (Fig. 1P-S). Although plasma CORT and ROS/RNS levels were unchanged (Fig. 1T, U), ROS/RNS in the mPFC increased significantly (Fig. 1V). GS activity and amino acid levels (Glu, Gln, GABA) were unaffected (Fig. 1W-Z). To see whether the increment of Glu in the synaptic cleft caused by GLT-1 cKO affects the expression of ionotropic glutamate receptors, the expression of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) [20] receptor subunit GluA1 and GluA2, and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit GluN2A and GluN2B were examined (Fig. 1a and b). Interestingly, GLT-1 deficiency altered glutamate receptor composition, decreasing the AMPA receptor subunit GluA2 and increasing NMDA receptor subunits GluN2A and GluN2B (Fig. 1a-d), suggesting a change of glutamate receptor-mediated excitatory signaling in the mPFC.

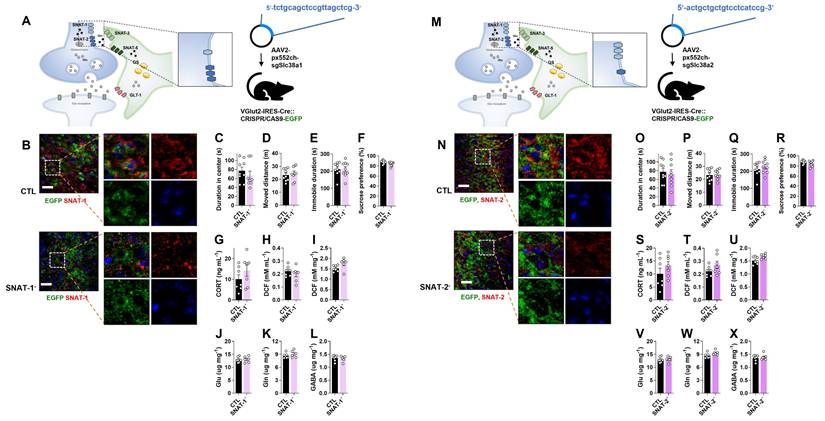

Single knockout of SNAT-1 (SNAT-1 cKO) or SNAT-2 (SNAT-2 cKO) in glutamatergic neurons has no effect on emotional behaviors and Glu-Gln levels

To assess the role of neuronal glutamine transporters in depression, either SNAT-1 or SNAT-2 was selectively knocked out (SNAT-1 cKO and SNAT-2 cKO) in glutamatergic neurons by injecting pAAV2.pX552ch-sgSlc38a1 or pAAV2.pX552ch-sgSlc38a2 into Vglut2-IRES-Cre::CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice, respectively (Fig. 2A, M). Successful deletion of either SNAT-1 or SNAT-2 was confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2B, N). Neither SNAT-1 nor SNAT-2 cKO mice exhibited depressive-like behaviors in the OFT, TST, or SPT (Fig. 2C-F, 2O-R). The levels of CORT, ROS/RNS, and amino acids (Glu, Gln, and GABA) were also unchanged (Fig. 2G-L, 2S-X).

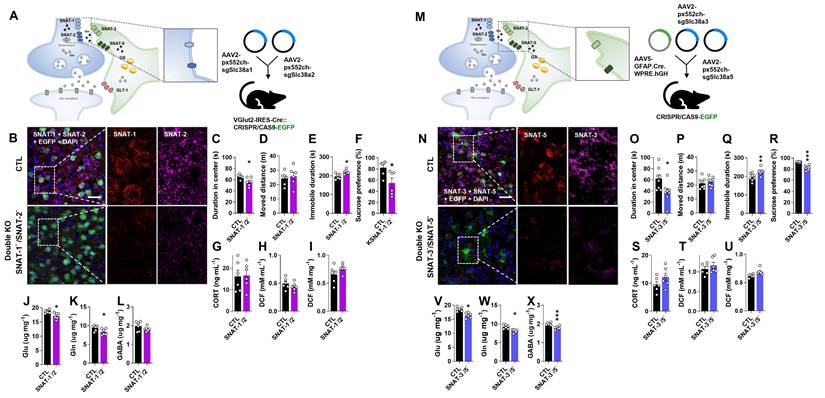

Changes of phenotype in neuronal sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter-1 (SNAT-1) and SNAT-2 cKO mouse (SNAT-1- and SNAT-2-). (A and M) Experimental scheme. The dotted and solid boxes indicate the target proteins of cKO and the expected change, respectively. The virus for small guide RNA (sgRNA) of each gene was injected into the prelimbic cortex of Vglut2-IRES-Cre::CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice. The blue sequences indicate the sgRNA nucleotide sequences. (B and N) EGFP (green), SNAT-1 or SNAT-2 (red) signals in the prelimbic cortex. Blue signals are DAPI. Scale bars = 50 μm. (C and D, O and P) Duration in center and moved distance measured in the open field test. (E and Q) Immobile duration measured in the tail suspension test. (F and R) Sucrose preference measured in the sucrose preference test. (G and S) Plasma corticosterone (CORT) level. (H and I, T and U) Reactive oxygen/nitrogen species level in the plasma and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). DCF, 2', 7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein. (J-L, V-X) Glutamate, glutamine, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels in mPFC. All data were represented as mean ± SEM and statistically analyzed by unpaired, two-tailed t-test (p < 0.05).

Changes of phenotype in astrocytic sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter-3 (SNAT-3) and SNAT-5 conditional knockout (cKO) mouse (SNAT-3- and SNAT-5-). (A and M) Experimental scheme. The dotted and solid boxes indicate the target proteins of cKO and the expected change, respectively. The two viruses for Cre recombinase and small guide RNA (sgRNA) were inserted into the prelimbic cortex of CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice. The blue sequences indicate the sgRNA nucleotide sequences. (B and N) EGFP (green), SNAT-3 or SNAT-5 (red) signals in the prelimbic cortex. Blue signals are DAPI. Scale bars = 50 μm. (C and D, O and P) Duration in center (C, t=2.440, df=16, p=0.027) and moved distance measured in the open field test. (E and Q) Immobile duration measured in the tail suspension test. (F and R) Sucrose preference measured in the sucrose preference test. (G and S) Plasma corticosterone (CORT) level. (H and I, T and U) Reactive oxygen/nitrogen species level in the plasma and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). DCF, 2', 7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein. (J-L, V-X) Glutamate (J, t=3.497, df=12, p=0.004), glutamine, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA, L, t=2.735, df=12, p=0.018; X, t=3.222, df=12, p=0.007) levels in mPFC. All data were represented as mean ± SEM and statistically analyzed by unpaired, two-tailed t-test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01).

Astrocyte-specific SNAT-3 knockout (SNAT-3 cKO) evokes anxious behavior with the reduction of Glu and GABA levels

To investigate the role of astrocytic SNAT-3 in depression, pAAV.GFAP.Cre.WPRE.hGH and pAAV2.pX552ch-sgSlc38a3 were co-injected into CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice (Fig. 3A). SNAT-3 immunoreactivity was markedly reduced in the mPFC of SNAT-3 cKO mice (Fig. 3B). In behavioral tests, SNAT-3 cKO mice spent less time in the center zone during the OFT, indicating increased anxiety-like behavior, while total locomotor activity was not affected (Fig. 3C and D). Performance in the TST and SPT was unchanged (Fig. 3C-F). Plasma CORT and ROS/RNS levels showed no changes (Fig. 3G-I). Amino acid analysis revealed selective reductions in Glu and GABA (Fig. 3J-L). These results suggest that astrocytic SNAT-3 loss alters neurotransmitter balance without inducing overt depressive-like behaviors.

Astrocyte-specific SNAT-5 knockout (SNAT-5 cKO) shows normal behaviors with only a decrease in GABA

To examine the role of astrocytic SNAT-5 in depression, pAAV.GFAP.Cre.WPRE.hGH and pAAV2.pX552ch-sgSlc38a5 were co-injected into the mPFC of CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice (Fig. 3M). SNAT-5 immunoreactivity was markedly reduced in the mPFC of SNAT-5 cKO mice (Fig. 3N). SNAT-5 cKO mice showed no abnormal behaviors in the OFT, TST, or SPT, and no significant changes were detected in plasma CORT, and ROS/RNS (Fig. 3O-U). Among amino acids, only GABA levels were decreased (Fig. 3X), suggesting a minor effect of astrocytic SNAT-5 loss on GABA-mediated inhibitory neurotransmission without behavioral consequences.

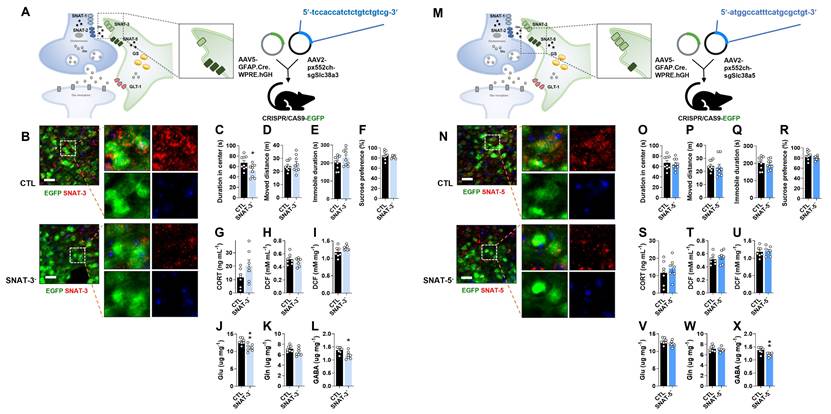

Glutamatergic neuronal specific double knockout of SNAT-1 and SNAT-2 (SNAT-1/SNAT-2 dcKO) induces depressive-like behaviors with a decrement of Glu and Gln

To investigate the combined role of neuronal glutamine transporters, SNAT-1 and SNAT-2 double conditional knockout (SNAT-1/SNAT-2 dcKO) mice were generated by co-injecting pAAV2.pX552ch-sgSlc38a1 and pAAV2.pX552ch-sgSlc38a2 into Vglut2-IRES-Cre::CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice (Fig. 4A). Immunohistochemistry confirmed a marked reduction of both SNAT-1 (violet) and SNAT-2 (red) signals (Fig. 4B). Unlike the single knockouts (SNAT-1 cKO and SNAT-2 cKO), SNAT-1/SNAT-2 dcKO mice exhibited clear depressive phenotypes across all behavioral tests, including OFT, TST, and SPT (Fig. 4C-F). However, CORT and ROS/RNS levels remained unchanged in both plasma and mPFC (Fig. 4G-I). Amino acid analysis revealed significant reductions in Glu and Gln (Fig. 4J-L), suggesting that concurrent loss of neuronal SNAT-1 and SNAT-2 critically impairs the Glu-Gln cycle, leading to depressive-like phenotypes.

Astrocyte-specific double knockout of SNAT-3 and SNAT-5 (SNAT-3/SNAT-5 dcKO) results in depressive-like behaviors and decrements of Glu, Gln, and GABA

To examine the combined roles of astrocytic glutamine transporters, SNAT-3 and SNAT-5 double conditional knockout (SNAT-3/SNT-5 dcKO) mice were generated by co-injecting pAAV.GFAP.Cre.WPRE.hGH, pAAV2.pX552ch-sgSlc38a3, and pAAV2.pX552ch-sgSlc38a5 into CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice (Fig. 4M). Immunohistochemistry confirmed markedly reduced SNAT-3 (violet) and SNAT-5 (red) signals in the mPFC (Fig. 4N). SNAT-3/SNAT-5 dcKO mice exhibited pronounced depressive behaviors across the OFT, TST, and SPT compared with CTL (Fig. 4O-R). However, CORT and ROS/RNS levels were unchanged (Fig. 4S-U). Notably, the concentrations of Glu, Gln, and GABA were all significantly decreased (Fig. 4V-X), suggesting that concurrent loss of SNAT-3 and SNAT-5 severely disrupts the Glu-Gln-GABA cycle, leading to depressive-like phenotypes.

Changes of phenotype in double conditional knockout (dcKO) of SNAT-1/SNAT-2 and SNAT-3/SNAT-5 mouse (SNAT-1-/SNAT-2- and SNAT-3-/SNAT-5-). (A and M) Experimental scheme. The dotted and solid boxes indicate the target proteins of dcKO and the expected change, respectively. For dcKO of neuronal SNATs (SNAT-1-/SNAT-2-), the two viruses with sgRNA were injected into prelimbic cortex of Vglut2-IRES-Cre::CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice. For dcKO of astrocytic SNATs (SNAT-3-/SNAT-5-), one virus for Cre recombinase and two viruses for sgRNA were inserted prelimbic cortex of CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice. (B and N) Green is for EGFP, red is for SNAT-1 or SNAT-5, and violet is for SNAT-2 or SNAT-3 in the prelimbic cortex. Blue is for DAPI. Scale bars = 50 μm. (C and D, O and P) Duration in center (C, t=2.636, df=10, p=0.025; O, t=2.604, df=14, p=0.021) and moved distance measured in open field test. (E and Q) Immobile duration (E, t=3.155, df=10, p=0.010; Q, t=3.160, df=14, p=0.007) measured in tail suspension test. (F and R) Sucrose preference (F, t=2.669, df=10, p=0.0241; R, t=7.196, df=14, p<0.001) measured in sucrose preference test. (G and S) Plasma corticosterone (CORT) level. (H and I, T and U) Reactive oxygen/nitrogen species level in the plasma and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). DCF, 2', 7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein. (J-L, V-X) Glutamate (J, t=2.926, df=10, p=0.015; S, t=4.317, df=10, p=0.002), glutamine (K, t=2.200, df=10, p=0.026; T, t=3.790, df=10, p=0.004), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA, U, t=4.834, df=10, p<0.001) levels in mPFC. All data were represented as mean ± SEM and statistically analyzed by unpaired, two-tailed t-test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001).

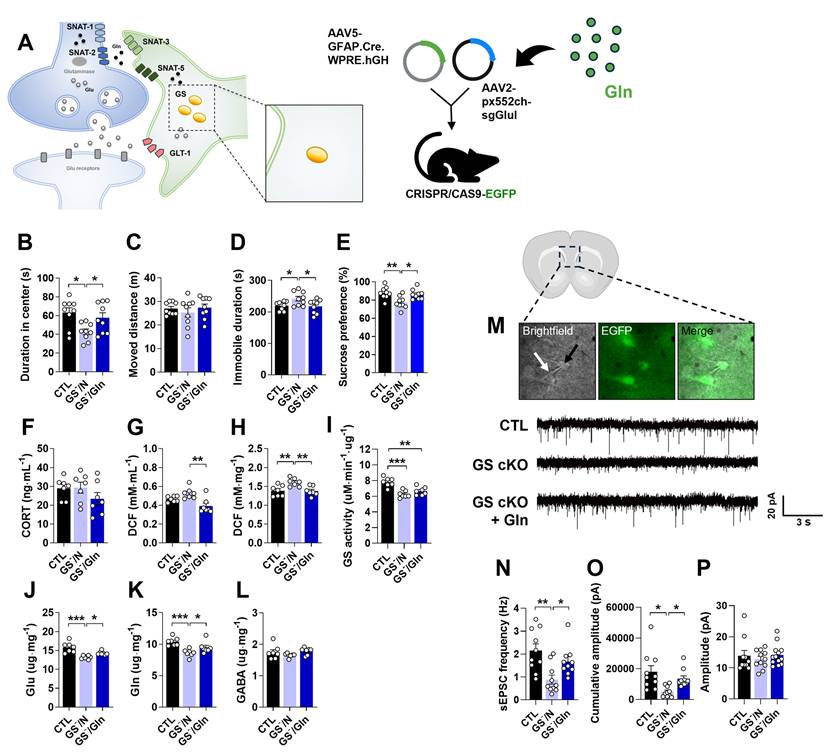

Gln supplementation ameliorates depressive-like behaviors and hypoactive glutamatergic neurotransmission in the mPFC of GS cKO

The depressive-like behaviors and decreased Glu-Gln levels observed in GS cKO mice (Fig. 1A-M) appear to correspond with the effects noted in the mouse model of depression induced by CIS [17, 19]. Given our previous findings that Gln exhibits an antidepressive effect in CIS-induced depressiveness, we examined whether Gln supplementation could ameliorate the deleterious effects of GS cKO. To this end, Gln was supplied to the GS cKO mice for one week before and two weeks after surgery (Fig. S1B). The GS cKO mice treated with Gln exhibited behaviors in the OFT, TST, and SPT that were similar to those observed in the CTL (Fig. 5B-E). This result provides strong evidence that Gln supplementation effectively reversed the depressive phenotype. Interestingly, the stress bio-marker CORT level remained indifferent among groups, including the Gln-treated GS cKO group (Fig. 5F). In GS cKO mice, the increased levels of ROS/RNS were decreased by Gln supplementation, bringing them back to CTL levels in both plasma and mPFC (Fig. 5G and H). Similar to its impact on the CIS-induced depression mouse model [18], Gln supplementation did not alter GS activity in GS cKO mice (Fig. 5I) but instead compensated for the Glu and Gln deficiencies, rescuing them to the CTL levels (Fig. 5J and K), indicating a recovery of the Glu-Gln balance. GABA level, however, showed no significant difference across the three groups (Fig. 5L). Given that the disturbance of Glu-Gln balance in the mPFC affects glutamatergic neurotransmission, we investigated sEPSC to assess synaptic function (Fig. 5M). The frequency of sEPSC, which was lower in GS cKO compared to CTL, returned to the CTL level after Gln supplementation (Fig. 5N). Moreover, in the GS cKO, the cumulative amplitude was reduced, but it was reversed by Gln supplementation (Fig. 5O). There was no difference in the average amplitude size among the three groups (Fig. 5P). These electrophysiological results indicate that Gln supplementation can preserve glutamatergic synaptic function in the mPFC by ammeliorating disrupted Glu-Gln homeostasis.

Anti-depressive effects of Gln supplementation in GS cKO mouse. (A) Experimental scheme. The dotted and solid boxes indicate the target proteins of cKO and the expected change, respectively. The two viruses for Cre recombinase and small guide RNA (sgRNA) were injected into the prelimbic cortex of CRISPR/CAS9-EGFP mice. Gln diet was provided to mice from 7 d before surgery to decapitation. (B and C) Duration in center (B, F(2,24)=5.349, p=0.012) and moved distance measured in the open field test. (D) Immobile duration (F(2,24)=4.128, p=0.029) measured in the tail suspension test. (E) Sucrose preference (F(2,24)=7.467, p=0.003) measured in the sucrose preference test. (F) Plasma corticosterone (CORT) level. (G and H) Reactive oxygen/nitrogen species level in plasma (F(2,18)=8.907, p=0.002) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC, F(2,18)=7.418, p=0.005). DCF, 2', 7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein. (I) GS activity in the mPFC. (J-L) Glutamate (F(2,18)=15.74, p<0.001), glutamine (F(2,18)=10.34, p=0.001), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels in mPFC. (M) Measuring of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSC) using patch clamp probe (white arrow) in glutamatergic neuron (green, black arrow) of prelimbic cortex, and sEPSC recordings measured. (N-P) sEPSC frequency (F(2,31)=5.662, p=0.008), cumulative amplitude (F(2,31)=5.499, p=0.009), and average amplitude. All data were represented as mean ± SEM and statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Dunnett′s Multiple Comparison Test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001).

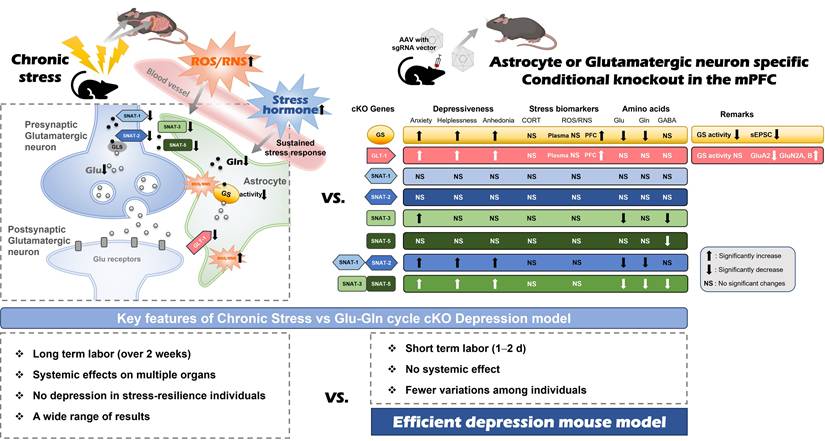

Comparison between chronic immobilization stress (CIS)-induced depression model (left) and astrocyte- or glutamatergic neuron-specific conditional knockout (cKO) mouse (right). The astrocyte or glutamatergic neuron-specific cKO mice have the advantages of a short labor time, no systematic effects, and fewer experimental variations among individuals compared to the CIS model, so it can be used as an effective depression animal model.

Discussion

The importance of the glutamatergic system in the PFC has recently emerged, supported by a multitude of preclinical and clinical studies that reinforce the glutamate hypothesis [10, 14, 17, 21, 22]. We previously reported a decrease in GS activity and a downregulation of protein expression associated with the Glu-Gln cycle, including GLT-1, SNAT-1, SNAT-2, SNAT-3, and SNAT-5, in the mPFC of mice with CIS-induced depression [14, 17, 18]. The objective of this research was to elucidate the functions of these proteins in the manifestation of typical emotional behaviors and to pinpoint the critical factors that cause the transition from normal to depressive-like behaviors (Fig. 6).

Within the proteins associated with the Glu-Gln cycle, GS serves a critical function in the recycling process of Glu absorbed from the synaptic cleft. Our prior research indicated that the inhibition of GS or the ablation of astrocytes led to the manifestation of depressive behaviors [14]. It was also demonstrated that the reduction of GS activity induced by CIS exerts a causative influence on depressive-like behaviors, with its activity being downregulated via tyrosine nitration by peroxynitrite, which is augmented by CIS [17, 19]. Furthermore, CIS-induced depressive-like behaviors were ameliorated through Gln-supplementation or the process of denitration by means of tyrosine and tyrosyl-glutamine [17, 19]. Consequently, we hypothesized that the abrogation of GS activity would manifest depressive phenotypes and a reduction in Glu-Gln concentrations within the mPFC. Our current research, employing the GS cKO model, has tested and confirmed this hypothesis to be the case. Alongside these phenotypes, we observed an elevation in ROS/RNS levels, which was associated with a reduction in GS activity. Although synaptic Glu-Gln cycling and neuronal activity are likely diminished in GS cKO mice, the astrocytic build-up of Glu and ammonium may lead to a metabolic burden and oxidative/nitrosative stress within astrocytes, a situation attributed to GS deficiency [23]. The compartmentalized reaction, characterized by reduced neurotransmission along with heightened astrocytic metabolic stress, may explain the paradoxical increase in ROS/RNS levels. These alterations, instigated by GS cKO, consequently culminated in hypoactive glutamatergic neurotransmission as demonstrated in the CIS-induced depression mouse model [17, 19], which predominantly accounts for the manifestation of depressive-like behaviors. Hence, our results indicate that an unimpaired GS function may be essential for preserving normal emotional behaviors.

Our findings further imply the potential applicability of GS cKO as an alternative to the CIS-induced depression mouse. To evaluate this potential, Gln was administered to GS cKO mice due to the known antidepressant properties of Gln [17, 18]. Gln-administered GS cKO mice exhibited emotional behaviors and sEPSC that were comparable to the control group. Gln supplementation resulted in a reduction of ROS/RNS levels. Notably, there was no alteration in GS activity, which is consistent with our prior findings [17]. We thus propose that GS cKO may serve as a model for the development of novel antidepressants aimed at mitigating depressive behaviors induced by chronic stress.

Gln, which is converted from Glu in astrocytes, is transported to glutamatergic neurons. This is mediated by the SNAT family. Consequently, it has been proposed that the expression levels of the SNAT family are significantly linked to depressive behaviors, with a decrease in their expression closely associated with a higher incidence of suicidal behavior [24]. Inhibition of neuronal glutamine transporters resulted in decreased levels of Glu-Gln in the mPFC and manifested depressive-like behaviors [14], and a reduction of their expression was observed in CIS-induced depressive mice [18]. Furthermore, the reduction in the expression of SNAT-3 and SNAT-5 in astrocytes was also validated [18]. Nevertheless, there is a paucity of information regarding the role of these SNATs in the regulation of normal behaviors. To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate neuron-specific cKO of SNAT-1 or SNAT-2 in the mPFC, along with astrocyte-specific cKO of SNAT-3 or SNAT-5. Through this methodology, we confirmed the distinct roles of these in maintaining the homeostasis of the Glu-Gln cycle and the expression of normal behaviors. It is notable that no substantial alteration was observed in the single cKO of SNAT-1 or SNAT-2. On the other hand, the dcKO of SNAT-1/SNAT-2 resulted in depressive-like behavior and decreased levels of Glu-Gln, which is consistent with the results observed when their function is inhibited [14, 25]. The findings suggest that the two transporters fulfill complementary roles in the uptake of glutamine into glutamatergic neurons. Conversely, anxiety-like behavior and a reduction in Glu and GABA levels were observed with SNAT-3 cKO. While depressive-like behavior was absent in SNAT-5 cKO, a reduction in GABA levels was noted. The phenotypes in the single cKO of SNAT-3 or SNAT-5 appeared less pronounced compared to the pronounced depressiveness and diminished Glu-Gln levels in SNAT-3/SNAT-5 dcKO. This observation implies that the roles of SNAT-3 and SNAT-5 appear to be somewhat asymmetrically arranged compared to the compensatory roles of SNAT-1 and SNAT-2 in neurons.

The tripartite synapse consists of presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons, in addition to an astrocyte, with the potential for the neurons to be either glutamatergic or GABAergic in nature [26, 27]. The cycle involving astrocytes and GABAergic neurons is referred to as the GABA-Gln cycle. Within this cycle, GABA is absorbed by GABA transporter-1 located in astrocytes and subsequently converted into Gln, which is then conveyed to GABAergic neurons [26]. Notably, a reduction in GABA levels was observed in all SNAT-3, SNAT-5 cKO, and SNAT-3/SNAT-5 dcKO conditions, whereas the GABA level remained unchanged in other cKOs with normal SNAT-3 and SNAT-5 expression (Fig. 6). These findings suggest that adequate exportation of Gln from astrocytes represents a crucial regulatory point for maintaining GABA levels in the brain, achievable solely via the function of both SNAT-3 and SNAT-5.

Recent studies have proposed that the antidepressant esketamine obstructs NMDA receptors on GABAergic neurons, leading to the disinhibition of glutamatergic neurons, thereby inducing a rapid increase in glutamatergic signaling within the mPFC [28-30]. However, if patients exhibit insufficient functionality of SNAT-3 or SNAT-5 within the mPFC, the resultant decrease in GABA levels would lead to a diminished inhibitory effect of GABAergic neurons on glutamatergic neurons. Consequently, the patient may exhibit an inadequate response to esketamine [31]. In such a case, alternative therapeutic approaches need to be considered, and our SNAT-3 and SNAT-5 cKO models may serve as appropriate animal models for the development of novel antidepressants to offset esketamine.

Incomplete clearance of glutamate by astrocytes has been noted in various psychiatric disorders [32-34], and the reduced expression of GLT-1 in the brain has been posited to be intricately associated with depression [18, 35, 36]. From this perspective, the manifestation of depressive symptoms in GLT-1 cKO was anticipated. Nevertheless, the phenotype exhibited by GLT-1 cKO presents as particularly intriguing when juxtaposed with our prior hypothesis, which suggested that the augmentation of ROS/RNS in the PFC would mitigate GS activity through tyrosine nitration, thereby leading to reduced levels of Glu-Gln and diminished glutamatergic signaling [17, 19]. GLT-1 cKO exhibits depressive phenotypes accompanied by an elevation of ROS/RNS in the mPFC, while the activity of GS and the levels of Glu-Gln appear to remain unchanged. Consequently, the depressive manifestations observed in GLT-1 cKO may be induced by alternative mechanisms. GLT-1 is predominantly expressed in astrocytes and at reduced levels within excitatory presynaptic terminals [13, 37]. The ablation of GLT-1 from astrocytes across the entire brain resulted in merely a 15% decrease in Glu uptake into forebrain synaptosomes. Conversely, the neuronal deletion of GLT-1 led to a reduction of synaptosomal Glu uptake to 40% of that observed in the wild type [37]. It is plausible that the GLT-1 cKO retains a considerable proportion (~80%) of Glu synaptosomes as found in CTL, potentially reliant on the Glu-Gln cycle facilitated by the Glu aspartate transporter (GLAST) in astrocytes and GLT-1 in presynaptic neurons. Consequently, no significant alterations in the Glu-Gln levels have been observed in GLT-1 cKO in this study.

While a substantial portion of Glu in the synaptic cleft is cleared by GLAST and neuronal GLT-1, there remains an excess of Glu within the synaptic cleft, influencing the postsynaptic neuronal excitability. Should the postsynaptic neurons incur damage due to excitotoxicity, abnormal behaviors would be expected during behavioral assessments. However, no abnormal behaviors are observed within their home environments or during behavioral tests, as indicated by consistent movement distances in the OFT. Previous research has also indicated that susceptibility to excitotoxicity is predominantly contingent upon GLT-1 in presynaptic terminals rather than in astrocytes [37, 38]. Hence, GLT-1 cKO appears unaffected by the augmented excitatory Glu stimulation resulting from an increased Glu within the synaptic cleft.

Excitotoxicity requires the excessive activation of Glu receptors on postsynaptic neurons. Conversely, desensitization of Glu receptors can serve as a protective mechanism against excitotoxicity and may function as a feedback system to mitigate the adverse effects of excessive Glu [39, 40]. Glu initially activates AMPA receptors, given their primary responsibility for rapid neurotransmission, and then activation of NMDA receptors occurs [41-44]. In this investigation, the expression of GluA2 is diminished by GLT-1 cKO, which appears to play a role in attenuating Glu-induced rapid depolarization. Notably, the expression of GluN2A and GluN2B subunits is elevated. Under normal physiological conditions, an augmented ligand does not necessitate an increased number of receptors if the affinity or sensitivity remains unaltered. Nonetheless, should the receptors undergo desensitization, the neuron might require a surge in receptor quantity to preserve its responsiveness to stimuli [45]. The NMDA receptor initiates a calcium influx upon activation, which subsequently stimulates the generation of superoxide within postsynaptic neurons [46]. GluN2B can produce nitric oxide (NO) through its interaction with postsynaptic density protein 95 and neuronal nitric oxide synthase [47]. NO reacts with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, which in turn leads to the nitration of tyrosine or the nitrosylation of cysteine residues within proteins, resulting in dysfunction [19, 48]. Indeed, both nitration and nitrosylation are proposed as therapeutic targets to ameliorate excitotoxic neuronal damage in severe excitotoxicity cases, such as stroke or epilepsy [48, 49]. The observed increase in ROS/RNS in GLT-1 cKO appears to manifest within postsynaptic neurons rather than astrocytes, as evidenced by the unchanged activity of GS. The escalation in ROS/RNS may be precipitated by NMDA receptor signaling in postsynaptic neurons, which leads to the desensitization of NMDA receptors through nitration and nitrosylation, thereby conferring protection against Glu-induced excitotoxicity. These processes may subsequently result in diminished glutamatergic signaling, which could underlie depressive behaviors in GLT-1 cKO. Similar to dysfunction states of SNAT-3 and SNAT-5, esketamine may not exert a therapeutic effect in patients lacking fully functional GLT-1 on astrocytes, due to the presence of desensitized NMDA receptors in the mPFC.

Animal models designed to study chronic stress-induced depression in numerous laboratory settings exhibit several constraints, such as prolonged labor requirements, unexpected extensive systemic effects, and markedly variable results attributable to the differing stress sensitivities of individual animals. However, the cKO models in this study can mitigate these limitations as they present certain advantages over chronic stress-induced depression models (Fig. 6). The cKOs targeting the Glu-Gln cycle proteins exhibit localized effects and can be produced using a relatively straightforward technique within a comparatively brief timeframe, which facilitates the generation of consistent phenotypes. Furthermore, the current study revealed the role for each Glu-Gln cycle component in depression pathogenesis. Consequently, it is anticipated that the cKOs of Glu-Gln cycle proteins may be beneficial as model systems in the testing of novel antidepressants.

Abbreviations

MDD: major depressive disorder; YLD: years lived with disability; Glu: glutamate; Gln: glutamine; mPFC: medial prefrontal cortex; GLT-1: glutamate transporter 1; GS: glutamine synthetase; SNAT: sodium-coupled neutral amino acid transporter; CIS: chronic immobilization stress; cKO: conditional knockout; sgRNA: small guide RNA; AAV: adeno-associated virus; OFT: open field test; TST: tail suspension test; SPT: sucrose preference test; CORT: corticosterone; GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid; PAGE: polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; sEPSC: spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current; AMPA: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; NDMA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; NO: nitric oxide.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and table.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF) (NRF-2019R1A2C1005020, RS-2022-NR069233, RS-2021-NR060105) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT of the Korea government. This study was also partially supported by the Research Resurgence under the Global University 30 Project at Gyeongsang National University in 2025.

Author contributions

JSK, JHB, HP, and DKL performed the experiments and analyzed the data. JSK wrote the original draft. NUR and HJC analyzed amino acids. SO designed the sgRNA, supervised the AAV synthesis, and contributed to the discussion and manuscript review/editing. HJK conceptualized the research, supervised the entire experiments and analyses, and contributed to the manuscript review/editing.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, Pariante CM, Etkin A, Fava M. et al. Major depressive disorder. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2016;2:16065

2. Bromet E, Andrade LH, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, de Girolamo G. et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC medicine. 2011;9:90

3. Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association. 2014;13:153-60

4. Luykx JJ, Laban KG, van den Heuvel MP, Boks MP, Mandl RC, Kahn RS. et al. Region and state specific glutamate downregulation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of (1)H-MRS findings. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2012;36:198-205

5. Taylor MJ. Could glutamate spectroscopy differentiate bipolar depression from unipolar? Journal of affective disorders. 2014;167:80-4

6. Arnone D, Mumuni AN, Jauhar S, Condon B, Cavanagh J. Indirect evidence of selective glial involvement in glutamate-based mechanisms of mood regulation in depression: meta-analysis of absolute prefrontal neuro-metabolic concentrations. European neuropsychopharmacology: the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;25:1109-17

7. Bremner JD, Vythilingam M, Vermetten E, Nazeer A, Adil J, Khan S. et al. Reduced volume of orbitofrontal cortex in major depression. Biological psychiatry. 2002;51:273-9

8. Murray EA, Wise SP, Drevets WC. Localization of dysfunction in major depressive disorder: prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Biological psychiatry. 2011;69:e43-54

9. Fuchikami M, Thomas A, Liu R, Wohleb ES, Land BB, DiLeone RJ. et al. Optogenetic stimulation of infralimbic PFC reproduces ketamine's rapid and sustained antidepressant actions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:8106-11

10. Moriguchi S, Takamiya A, Noda Y, Horita N, Wada M, Tsugawa S. et al. Glutamatergic neurometabolite levels in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:952-64

11. McIntyre RS, Jain R. Glutamatergic Modulators for Major Depression from Theory to Clinical Use. CNS Drugs. 2024;38:869-90

12. Lupien SJ, Juster RP, Raymond C, Marin MF. The effects of chronic stress on the human brain: From neurotoxicity, to vulnerability, to opportunity. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2018;49:91-105

13. McNair LF, Andersen JV, Aldana BI, Hohnholt MC, Nissen JD, Sun Y. et al. Deletion of Neuronal GLT-1 in Mice Reveals Its Role in Synaptic Glutamate Homeostasis and Mitochondrial Function. J Neurosci. 2019;39:4847-63

14. Lee Y, Son H, Kim G, Kim S, Lee DH, Roh GS. et al. Glutamine deficiency in the prefrontal cortex increases depressive-like behaviours in male mice. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013;38:183-91

15. Banasr M, Chowdhury GM, Terwilliger R, Newton SS, Duman RS, Behar KL. et al. Glial pathology in an animal model of depression: reversal of stress-induced cellular, metabolic and behavioral deficits by the glutamate-modulating drug riluzole. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:501-11

16. Banasr M, Duman RS. Glial loss in the prefrontal cortex is sufficient to induce depressive-like behaviors. Biological psychiatry. 2008;64:863-70

17. Son H, Baek JH, Go BS, Jung DH, Sontakke SB, Chung HJ. et al. Glutamine has antidepressive effects through increments of glutamate and glutamine levels and glutamatergic activity in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2018;143:143-52

18. Baek JH, Vignesh A, Son H, Lee DH, Roh GS, Kang SS. et al. Glutamine Supplementation Ameliorates Chronic Stress-induced Reductions in Glutamate and Glutamine Transporters in the Mouse Prefrontal Cortex. Exp Neurobiol. 2019;28:270-8

19. Kang JS, Kim H, Baek JH, Song M, Park H, Jeong W. et al. Activation of glutamine synthetase (GS) as a new strategy for the treatment of major depressive disorder and other GS-related diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2025;46:880-91

20. Pose-Utrilla J, Garcia-Guerra L, Del Puerto A, Martin A, Jurado-Arjona J, De Leon-Reyes NS. et al. Excitotoxic inactivation of constitutive oxidative stress detoxification pathway in neurons can be rescued by PKD1. Nat Commun. 2017;8:2275

21. Sanacora G, Treccani G, Popoli M. Towards a glutamate hypothesis of depression: an emerging frontier of neuropsychopharmacology for mood disorders. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:63-77

22. Hasler G, van der Veen JW, Tumonis T, Meyers N, Shen J, Drevets WC. Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:193-200

23. Lemberg A, Fernandez MA. Hepatic encephalopathy, ammonia, glutamate, glutamine and oxidative stress. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8:95-102

24. Ernst C, Dumoulin P, Cabot S, Erickson J, Turecki G. SNAT1 and a family with high rates of suicidal behavior. Neuroscience. 2009;162:415-22

25. Son H, Jung S, Shin JH, Kang MJ, Kim HJ. Anti-Stress and Anti-Depressive Effects of Spinach Extracts on a Chronic Stress-Induced Depression Mouse Model through Lowering Blood Corticosterone and Increasing Brain Glutamate and Glutamine Levels. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 7

26. Bak LK, Schousboe A, Waagepetersen HS. The glutamate/GABA-glutamine cycle: aspects of transport, neurotransmitter homeostasis and ammonia transfer. J Neurochem. 2006;98:641-53

27. Perea G, Navarrete M, Araque A. Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:421-31

28. Luscher B, Feng M, Jefferson SJ. Antidepressant mechanisms of ketamine: Focus on GABAergic inhibition. Adv Pharmacol. 2020;89:43-78

29. Gerhard DM, Pothula S, Liu RJ, Wu M, Li XY, Girgenti MJ. et al. GABA interneurons are the cellular trigger for ketamine's rapid antidepressant actions. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:1336-49

30. Zhang B, Yang X, Ye L, Liu R, Ye B, Du W. et al. Ketamine activated glutamatergic neurotransmission by GABAergic disinhibition in the medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2021;194:108382

31. Reif A, Bitter I, Buyze J, Cebulla K, Frey R, Fu DJ. et al. Esketamine Nasal Spray versus Quetiapine for Treatment-Resistant Depression. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1298-309

32. Karlsson RM, Tanaka K, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Heilig M, Holmes A. Assessment of glutamate transporter GLAST (EAAT1)-deficient mice for phenotypes relevant to the negative and executive/cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1578-89

33. Gourley SL, Espitia JW, Sanacora G, Taylor JR. Antidepressant-like properties of oral riluzole and utility of incentive disengagement models of depression in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2012;219:805-14

34. Guan Y, Liu X, Su Y. Ceftriaxone pretreatment reduces the propensity of postpartum depression following stroke during pregnancy in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2016;632:15-22

35. Veeraiah P, Noronha JM, Maitra S, Bagga P, Khandelwal N, Chakravarty S. et al. Dysfunctional glutamatergic and gamma-aminobutyric acidergic activities in prefrontal cortex of mice in social defeat model of depression. Biological psychiatry. 2014;76:231-8

36. Bernard R, Kerman IA, Thompson RC, Jones EG, Bunney WE, Barchas JD. et al. Altered expression of glutamate signaling, growth factor, and glia genes in the locus coeruleus of patients with major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:634-46

37. Petr GT, Sun Y, Frederick NM, Zhou Y, Dhamne SC, Hameed MQ. et al. Conditional deletion of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 reveals that astrocytic GLT-1 protects against fatal epilepsy while neuronal GLT-1 contributes significantly to glutamate uptake into synaptosomes. J Neurosci. 2015;35:5187-201

38. Rimmele TS, Li S, Andersen JV, Westi EW, Rotenberg A, Wang J. et al. Neuronal Loss of the Glutamate Transporter GLT-1 Promotes Excitotoxic Injury in the Hippocampus. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:788262

39. Brorson JR, Manzolillo PA, Gibbons SJ, Miller RJ. AMPA receptor desensitization predicts the selective vulnerability of cerebellar Purkinje cells to excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4515-24

40. Vyklicky L Jr. Calcium-mediated modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) responses in cultured rat hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 1993;470:575-600

41. Mayer ML. Glutamate receptor ion channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:282-8

42. Armstrong N, Sun Y, Chen GQ, Gouaux E. Structure of a glutamate-receptor ligand-binding core in complex with kainate. Nature. 1998;395:913-7

43. Furukawa H, Singh SK, Mancusso R, Gouaux E. Subunit arrangement and function in NMDA receptors. Nature. 2005;438:185-92

44. Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. AMPA receptor trafficking at excitatory synapses. Neuron. 2003;40:361-79

45. Hansen KB, Yi F, Perszyk RE, Menniti FS, Traynelis SF. NMDA Receptors in the Central Nervous System. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1677:1-80

46. Girouard H, Wang G, Gallo EF, Anrather J, Zhou P, Pickel VM. et al. NMDA receptor activation increases free radical production through nitric oxide and NOX2. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2545-52

47. Vieira M, Yong XLH, Roche KW, Anggono V. Regulation of NMDA glutamate receptor functions by the GluN2 subunits. J Neurochem. 2020;154:121-43

48. Nakamura T, Lipton SA. Protein S-Nitrosylation as a Therapeutic Target for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:73-84

49. Zhan X, Huang Y, Qian S. Protein Tyrosine Nitration in Lung Cancer: Current Research Status and Future Perspectives. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25:3435-54

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Hyun Joon Kim: kimhjac.kr, +82-55-772-8034 (H.J. Kim). Sekyung Oh: ohskjhmiac.kr, +82 32-290-2776 (S. Oh).

Corresponding author: Hyun Joon Kim: kimhjac.kr, +82-55-772-8034 (H.J. Kim). Sekyung Oh: ohskjhmiac.kr, +82 32-290-2776 (S. Oh).

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact