Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(2):750-770. doi:10.7150/ijbs.125140 This issue Cite

Review

Microbiota-gut-kidney axis in health and renal disease

1. School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, No. 548 Binwen Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310053, China.

2. Department of Medicine, Rhode Island Hospital and Alpert Medical School, Brown University, 593 Eddy St, Providence, Rhode Island, 02903, USA.

3. Beijing Key Lab for Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases, Institute of Clinical Medical Science, Department of Nephrology, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing 100029, China.

#These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-9-13; Accepted 2025-11-25; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Gut microbiota plays a central role in programming host metabolic function and immune modulation in both health and disease. Microbial dysbiosis leads to an increase in opportunistic pathogens and a reduction in beneficial bacteria, which collectively result in the excessive production of detrimental metabolites, particularly uremic toxins such as indoxyl sulfate and trimethylamine-N-oxide, while concurrently decreasing beneficial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids and tryptophan catabolites, including indole-3-aldehyde. The accumulation of harmful metabolites and depletion of protective metabolites contribute to fibrosis progression through various mediators, including the renin-angiotensin system, reactive oxygen species, Toll-like receptor 4, aryl hydrocarbon receptor, inhibitor of kappa B/nuclear factor kappa B, and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 pathways. This review highlights the pathogenic link between gut microbiota and kidney damage via the gut-kidney axis, encompassing acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Innovative therapeutic strategies, including microbial therapeutics (such as probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics), natural products (such as neohesperidin, isoquercitrin, and polysaccharides), and fecal microbiota transplantation, have been proposed to restore microbial balance and improve kidney function. Targeted modulation of the gut microbiota offers a promising strategy for developing novel treatments in AKI, CKD, and the transition from AKI-to-CKD. This approach has the potential to prevent or mitigate these conditions and their complications.

Keywords: gut microbiota, kidney disease, short-chain fatty acids, probiotics, sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitor, fecal microbiota transplantation

1. Introduction

Kidney diseases, including acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD), are major global public health problems that affect more than 10% of the adult population [1-3]. AKI is defined by a rapid elevation in serum creatinine levels, decreasing urine output, or both [4, 5]. AKI and CKD are interrelated clinical and pathophysiological disorders [6]. AKI can lead to a rapid decline in kidney function and may progress to CKD or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [7, 8], requiring renal replacement therapies, such as dialysis and transplantation [9, 10]. CKD significantly contributes to the burden of non-communicable diseases and correlates with various serious health outcomes, including an elevated risk of mortality, cardiovascular complications, and cognitive decline [11-13]. Additionally, kidney disease can occur alongside a variety of other conditions such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome (Figure 1) [14-17].

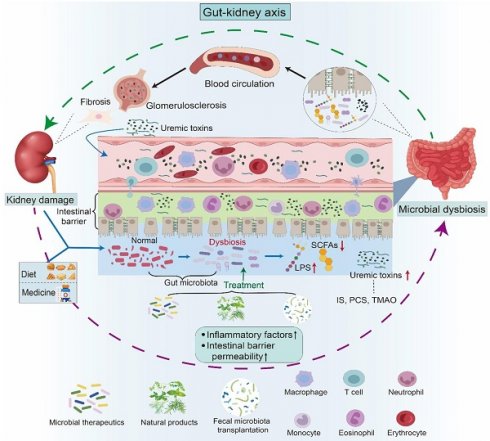

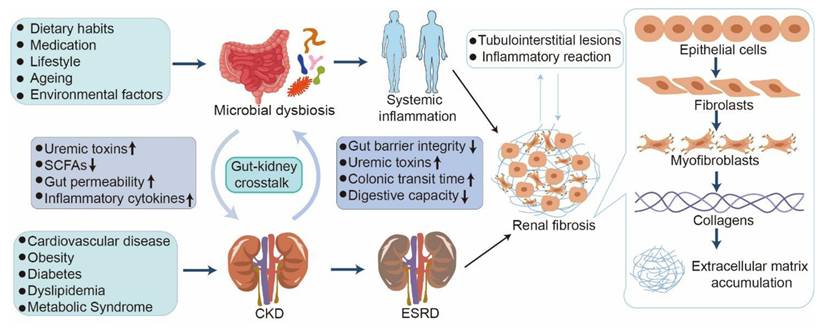

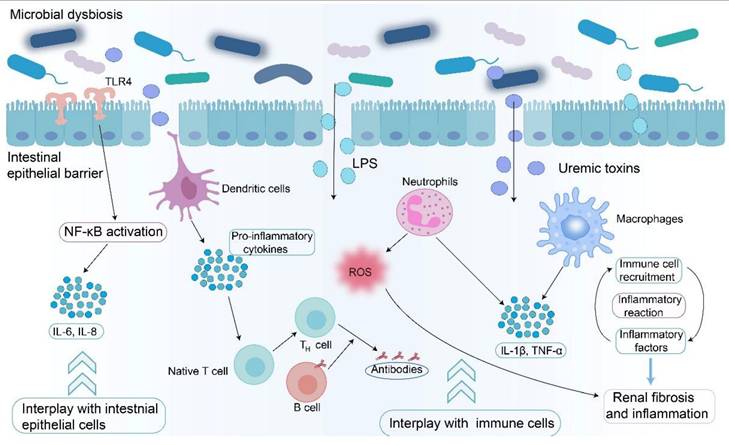

Crosstalk between microbial dysbiosis and CKD. CKD induces microbial dysbiosis, which compromises the intestinal mucosal barrier and allows harmful bacteria and uremic toxins to enter the bloodstream. The translocation of these noxious metabolites into circulation can induce oxidative stress and systemic inflammation, subsequently aggravating renal inflammation and fibrosis. During this process, myofibroblasts irreversibly form, followed by the production of multiple types of collagens and accumulation of extracellular matrix, eventually resulting in renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis.

Irrespective of the initial cause, renal fibrosis, including glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis (TIF), represents the terminal outcome of a wide variety of progressive kidney diseases [18, 19]. Renal fibrosis is characterized by excessive accumulation and deposition of extracellular matrix components in the kidney parenchyma, leading to tissue scarring (Figure 2) [20, 21]. Substantial evidence has shown that renal fibrosis is linked to hyperactive pro-fibrotic molecular players, such as the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), reactive oxygen species (ROS), Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) [22-25]. Numerous studies have revealed that aberrant pathways, including transforming growth factor-β/Smad (TGF-β/Smad), Wnt/β-catenin, inhibition of kappa B (IκB)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)/nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), are involved in renal fibrosis [23, 26, 27]. An increasing number of studies have highlighted that the dysregulation of metabolites, such as amino acids and lipids, including arachidonic acid (AA) and bile acid metabolism, are also implicated in renal fibrosis [28-31]. However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying this pathology remain unclear. Current treatments, including peritoneal dialysis, hemodialysis, colonic dialysis, and kidney transplantation, are costly and non-curative [32]. In this context, developing a strategy to target renal fibrosis is essential for effective treatment of patients with kidney disease.

Ample evidence shows dysbiosis of gut microbiota in AKI and CKD, such as diabetic kidney disease (DKD), membranous nephropathy (MN), immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), hypertensive nephropathy (HN), and lupus nephritis (LN), as well as renal replacement therapies including peritoneal dialysis (PD), hemodialysis (HD), and kidney transplantation [24, 33-38]. Microbial-derived metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, tryptophan derivatives, including indoxyl sulfate (IS), indole-3-aldehyde (IAld), and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and lipid derivatives, play a bridging role between the gut and host (Figure 2) [39, 40]. The accumulation of uremic toxins, such as IS, p-cresol sulfate (PCS), and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), due to persistent renal injury disrupts the balance of the gut microbiota (Figure 2) [39, 41, 42].

This review summarizes the dysbiosis of gut microbiota in kidney disease and elucidates the underlying molecular mechanisms of microbial dysbiosis through a broad spectrum of signaling pathways, such as TGF-β/Smad, IκB/NF-κB, Keap1/Nrf2, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K), and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), as well as key mediators, such as AHR, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, and G protein-coupled receptor 43 (GPR43), via alteration of diverse metabolites. Furthermore, targeting the gut microbiota by several therapeutic strategies, such as intestinal microbial therapeutics, natural products, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), are delineated (Figure 2). These findings shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying microbial dysbiosis in kidney disease and provide a clear pathophysiological rationale for treating AKI and CKD. This review provides a more specific concept-driven intervention strategy for developing precise mechanism-based management, prevention, and treatment of kidney disease.

2. Gut microbiota in health

The gut microbiota, comprising trillions of microorganisms predominantly inhabiting the gastrointestinal tract, plays a pivotal role in human health and extends beyond digestion [43-45]. This critical role encompasses immune modulation, metabolism, and the maintenance of homeostasis [44-47]. Gut microbiota homeostasis is influenced by dietary habits, lifestyle, medication use, ageing, and environmental factors (Figure 1) [24, 44, 47-49]. Meanwhile, changes in the microbial composition adversely affect kidney function, disease progression, and systemic inflammation (Figure 1) [24, 35, 50]. Gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in metabolic activities, including dietary fiber fermentation, SCFA production, and regulation of gut permeability (Figure 1) [51-53]. SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are pivotal for promoting anti-inflammatory responses and influencing systemic metabolism [53-57]. Furthermore, the gut microbiota interacts with the host immune system, facilitating immune cell maturation and modulating inflammatory pathways [57-59]. A balanced and diverse gut microbiota is integral to overall health, and dysbiosis has been associated with numerous health issues, including kidney diseases (Figure 1) [59-62].

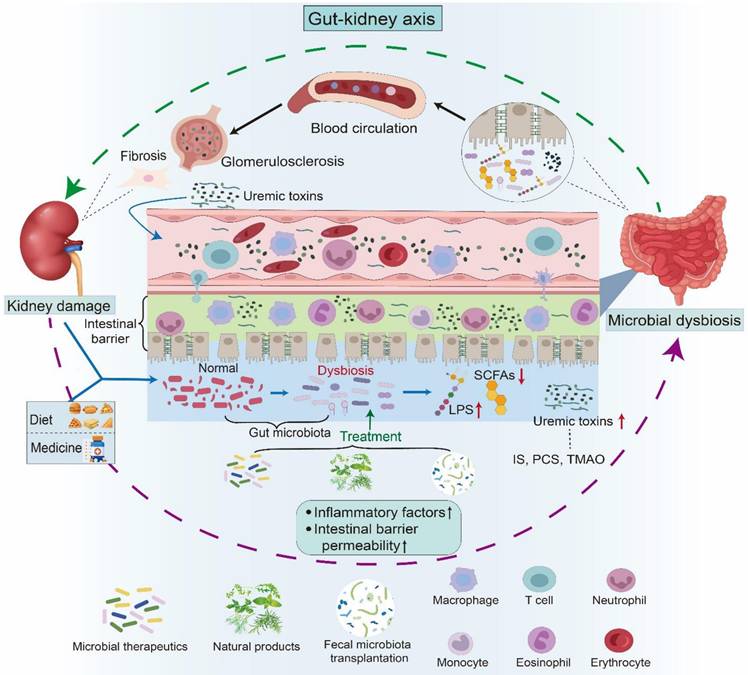

Gut-kidney axis and its impact on kidney health. The gut-kidney axis elucidates the relationship between the composition of the gut microbiota and kidney health. Kidney damage, including fibrosis and glomerular sclerosis, can lead to an imbalance in the gut microbiota, thereby affecting the permeability of the intestinal barrier. Concurrently, dietary intake and medication use also contribute to microbial dysbiosis. A disturbance in microbiota composition has been demonstrated to result in heightened levels of uremic toxins, including IS, PCS, and TMAO, along with a decline in LPS and beneficial short-chain fatty acids. Furthermore, compromised intestinal integrity facilitates the entry of uremic toxins into the systemic circulation. These harmful metabolites travel through the bloodstream to the kidneys, activating the corresponding pathways and triggering inflammation and immune responses, leading to kidney damage. Therapies such as microbial therapeutics, fecal microbiota transplantation, and natural products have been shown to influence kidney health by improving the imbalance in gut microbiota.

Intestinal flora has become a significant factor influencing an individual's overall health, preventing and developing various illnesses, including AKI, CKD, and their complications [63-65]. The gastrointestinal microbiome of healthy adults is composed of more than 1014 bacteria, of which a variety of bacteria come from four main bacterial phyla, including Firmicutes (79.4%), Bacteroidetes (16.9%), Actinobacteria (2.5%), Proteobacteria (1%), and Verrucomicrobia (0.1%) in human feces [66]. The Firmicutes phylum, which includes Lactobacillus and Enterococcus, is responsible for digesting complex carbohydrates and producing anti-inflammatory metabolites such as SCFAs, including butyrate, propionate, and acetate [53, 57]. The Bacteroidetes phylum, which includes Bacteroides and Prevotella, consists of anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria [44, 67]. Bacteroides serve as intestinal symbionts, forming a protective barrier against pathogens and aiding in the supply of nutrients to other microbiota [67, 68]. However, Prevotella colonization reduces SCFA production, increases susceptibility to mucosal inflammation, and stimulates immune cells to secrete inflammatory mediators [68, 69]. Actinobacteria, represented by Bifidobacteria, play a pivotal role in maintaining intestinal health [70]. An increase in Proteobacteria, including pathogens such as Escherichia coli (E. coli), is attributed to dysbiosis and exacerbates inflammation or enables the incursion of exogenous pathogens [71]. Akkermansia muciniphila, a member of the Verrucomicrobia, generates anti-inflammatory lipids and enhances the intestinal barrier function [72-74]. In summary, the concept of the gut-kidney axis has emerged, highlighting the bidirectional communication between gut microbiota and renal function (Figure 1) [75]. Given the pivotal role of the gut microbiota in maintaining health and its disruption in kidney disease, it is essential to explore how dysbiosis manifests in specific conditions such as AKI and the subsequent transition to CKD.

3. Gut microbial dysbiosis and dysregulation of microbial-derived metabolites in kidney disease

Under homeostatic conditions, the symbiotic interaction between microorganisms and the host facilitates metabolism and exerts diverse health benefits [44, 76, 77]. The commensal intestinal microflora stimulates and potentiates host immune response through nutrient competition, thereby hindering pathogens from establishing themselves in the host [44, 53, 78]. The intestinal microflora regulates immune, metabolic, and endocrine functions [53, 79, 80]. However, drug use and unhealthy diet lead to microbial dysbiosis, triggering metabolic disorders and adversely affecting kidney health (Figure 2) [24, 36]. This ecological disruption is typically characterized by the reduction of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which play a protective role against pathogenic organisms [24, 36, 81]. Concurrently, uncontrolled proliferation of harmful bacteria, such as certain strains of E. coli, leads to a shift in microbial composition that disrupts normal metabolic processes [82, 83]. This alteration results in the accumulation of toxic metabolites that can adversely affect renal function (Table 1) [84, 85]. Dysbiosis is also linked to systemic inflammation, a recognized factor in CKD progression [35, 84]. Excessive growth of pathogenic bacteria increases pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby exacerbating inflammatory responses and renal pathological injury [86]. For example, uremic toxins such as IS and PCS are generated through the metabolism of dietary proteins from pathogenic bacteria [87]. Their accumulation in the bloodstream, particularly when renal function is compromised, contributes to further kidney damage and associated metabolic disorders (Figure 2) [87]. Moreover, dysbiosis disrupts the metabolic pathways that govern energy homeostasis and nutrient absorption [88]. A reduction in the production of SCFAs, particularly butyrate, due to reduced populations of beneficial intestinal bacteria compromises the integrity of the intestinal barrier and promotes inflammation (Table 1) [89, 90]. These diminished SCFAs lead to increased intestinal permeability, facilitating translocation of bacterial endotoxins into systemic circulation, which further exacerbates inflammation and metabolic dysregulation (Table 1) [89, 90].

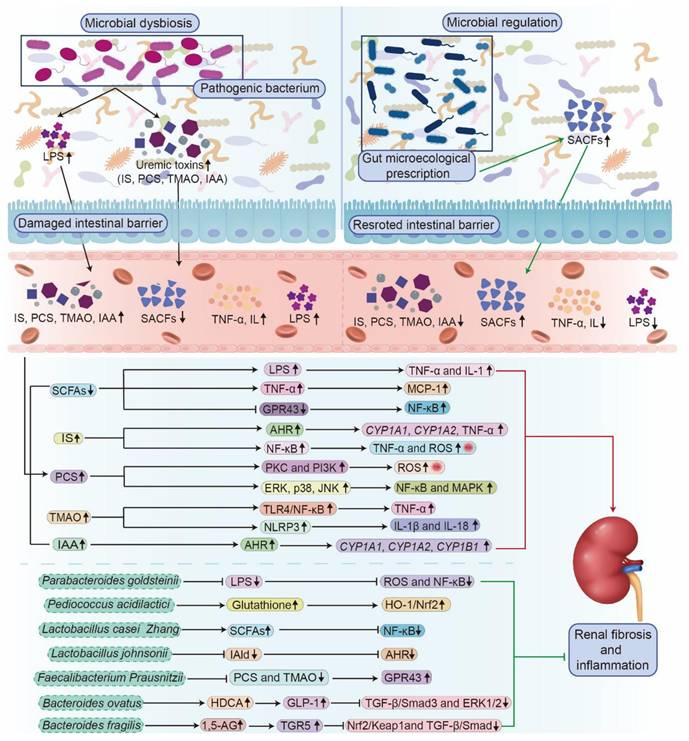

Evidence shows that SCFAs mitigate renal fibrosis by suppressing the expression of the pro-fibrotic chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) induced by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Figure 3) [88]. Furthermore, SCFAs activate GPR43, leading to blocking IκB phosphorylation and degradation, which inhibits NF-κB activity and reduces inflammatory gene expression (Figure 3) [88]. Concurrently, SCFAs strengthen the acetylation state of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) by inhibiting histone deacetylases (HDACs), which ultimately suppress lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-1, and nitrite synthesis while restraining renal tubular cell apoptosis (Figure 3) [88]. Additionally, an imbalance in intestinal flora also interferes with the metabolism of key nutrients, such as proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates, thereby influencing kidney health [91, 92]. Dysbiosis leads to impaired lipid metabolism, resulting in dyslipidemia, a common complication among patients with kidney disease that precipitates atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disorders [93]. Furthermore, dysbiosis worsens insulin resistance, complicating the management of metabolic disorders in patients with kidney disease [94, 95]. Taken together, gut microbial dysbiosis exerts a critical influence on individuals with kidney disease.

3.1 AKI

AKI is characterized by a rapid decline in renal function and is typically diagnosed by elevated serum creatinine levels and reduced urine output [4]. Diverse etiologies of AKI, including drug toxicity, ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), and sepsis, are associated with distinct alterations in gut microbiota composition [96-99]. Cisplatin is one of the most common causes of drug-induced AKI [96]. In animal models, cisplatin-induced AKI has been associated with an increased abundance of Allobaculum, Lactobacillus, Alloprevotella, and Bacteroides [96]. Similarly, Yang et al. reported that cisplatin-treated mice exhibited increased relative abundances of Dubosiella, Escherichia-Shigella, and Ruminococcus, along with decreased abundances of Ligilactobacillus and Anaerotruncus [97].

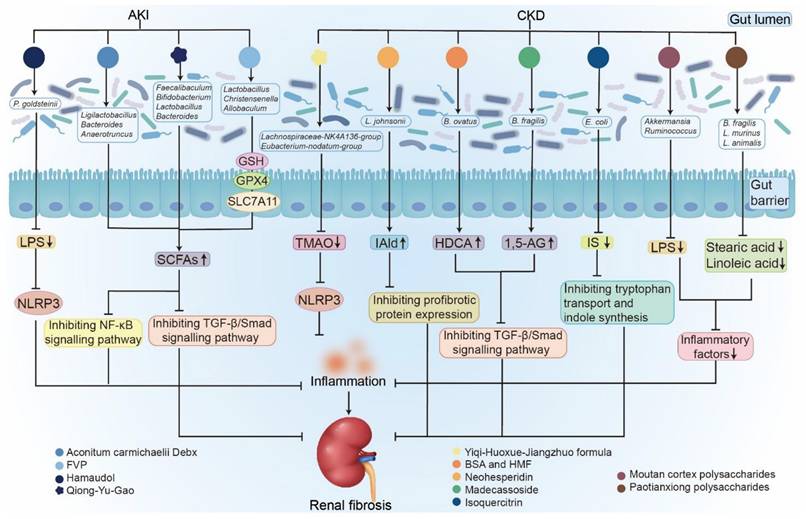

The molecular mechanism of kidney diseases mediated by microbial dysbiosis and the renal protective effect of gut microecological preparations. Dysbiosis, characterized by a reduction in beneficial SCFAs and an increase in uremic toxins (IS, PCS, TMAO, and IAA), damages the intestinal barrier and elevates LPS and pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL). These toxins and signals activate multiple inflammatory pathways and oxidative stress, collectively aggravating renal inflammation and fibrosis. Conversely, treatment with specific beneficial bacteria enhances their protective effects, such as producing SCFAs and lowering uremic toxins, leading to the suppression of NF-κB and TGF-β/Smad pathways, reducing oxidative stress, and activating the Nrf2 pathway. Thus, dysbiosis drives kidney damage through toxin release, barrier failure, and inflammation, while gut microecological preparations weaken the key mechanisms that regulate renal inflammation and fibrosis.

IRI has drawn considerable attention in experimental models. Compared with sham-operated controls, IRI mice demonstrated a decreased abundance of Bifidobacterium and increased abundances of Lactobacillus, Clostridium, and Ruminococcus [98]. In renal IRI-induced AKI models, the relative abundance of Parabacteroides goldsteinii (P. goldsteinii) was elevated, consistent with findings in patients with AKI [100]. Moreover, in sepsis-associated AKI, the accumulation of metabolic waste products caused by impaired renal excretion contributes to gut microbial dysbiosis [99]. In patients with sepsis, increased abundances of Enterobacteriaceae and Lachnospiraceae have been identified as predictors of subsequent AKI onset [100]. Winner et al. further reported that in a murine model of sepsis, elevated serum creatinine levels were accompanied by an increased relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae spp. [101]. During AKI, elevated inflammatory cytokines and ischemia alter the composition of the intestinal microbiota, leading to reduced microbial diversity and compromised intestinal barrier integrity [102]. Li et al. found that the relative abundances of Streptococcus, Escherichia, Pseudoflavonifractor, Rothia, Granulicatella, Peptostreptococcus, and Actinomyces increased in AKI patients, whereas Gemmiger, Erysipelatoclostridium, Coprococcus, and Ruminococcus decreased[103]. Microbial dysbiosis not only reduces SCFA levels, thereby aggravating inflammation and kidney injury, but also enhances the production of uremic toxins, accelerating renal deterioration (Figure 2) [102, 104]. In summary, AKI and gut microbial dysbiosis form a vicious cycle; renal injury promotes dysbiosis, which in turn exacerbates inflammation, oxidative stress, and toxin accumulation, thereby intensifying kidney damage and accelerating disease progression (Figure 2) [104].

3.2. Chronic renal injury

3.2.1. CKD

CKD is characterized by irreversible pathological injury that ultimately progresses to ESRD [105]. In a comparative study of healthy individuals and patients across five stages of CKD, the taxonomic chain Bacilli, Lactobacillales, Lactobacillaceae, Lactobacillus, and Lactobacillus johnsonii (L. johnsonii) was found to correlate with CKD progression. The abundance of L. johnsonii was associated with the estimated glomerular filtration rate and clinical markers of kidney function, including serum creatinine, urea, and cystatin C levels [106]. The serum concentration of IAld, a tryptophan catabolite produced by L. johnsonii, is decreased in late-stage CKD patients and in CKD rats induced with 5/6 nephrectomy (NX) or unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO), showing a negative correlation with serum creatinine (Table 1) [106]. IAld treatment ameliorated renal injury by inhibiting AHR pathway in rats with renal fibrosis and 1-hydroxypyrene-stimulated HK-2 cells. The protective effect of IAld was partially abrogated in AHR-deficient mice and HK-2 cells (Table 1) [106]. These findings provide mechanistic insights into how tryptophan metabolism mediated by gut microbiota influences CKD progression and identify a potential therapeutic target for intervention.

CKD patients also exhibit a decreased relative abundance of Faecalibacterium [107]. Several studies have reported reductions in Bacteroides fragilis (B. fragilis) and Bacteroides ovatus (B. ovatus) in CKD patients and UUO mice [108, 109]. The relative abundance of Clostridium scindens (C. scindens) was also decreased in UUO models [108]. Moreover, ESRD patients showed increased abundance of Eggerthella lenta, Flavonifractor plautii, Alistipes finegoldii, Alistipes shahii, Ruminococcus, and Fusobacterium, along with decreased abundance of Prevotella copri, Clostridium, and several butyrate-producing bacteria such as Roseburia, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Eubacterium rectale [110]. These compositional shifts are accompanied by elevated levels of uremic toxins (IS, PCS, indole, and p-cresol) and secondary bile acids derived from aromatic amino acid degradation and microbial secondary bile acid biosynthesis (Table 1) [110]. The decline in fecal SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, correlates with the reduction in SCFA-producing species in ESRD patients (Table 1) [110]. SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, exert protective effects on kidney diseases through the modulation of inflammation and oxidative stress, primarily via the activation of G protein-coupled receptors, leading to reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production, lowered oxidative stress markers, thereby improved renal function (Table 1) [89]. Therefore, reducing the number of bacteria that produce SCFAs disrupts the balance of metabolites produced by the intestinal microbiota, affecting their impact on the kidneys. For example, insufficient production of the protective compound butyrate reduces its anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic effects by inhibiting NF-κB pathway [89]. Concurrently, alterations in the gut microbiota impact uremic toxin metabolism, as certain butyrate-producing bacteria themselves contribute to indole sulfate production, which in turn exacerbates renal injury (Table 1) [84, 89]. These findings highlight the dysbiosis of the gut microbiota and dysregulation of microbial metabolites in CKD (Figure 2).

The effects of microbial-derived metabolites on kidney disease

| Metabolites | Microbial source | Disease models | Molecular mechanism | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS | C. sporogenes, C. bartlettii, B. longum, B. fragilis, P. distasonis, E. hallii | IS-induced mice, monocyte-derived macrophages, and IEC-6 Cells | Mediating renal fibrosis and inflammation by activating AHR and NF-κB pathways. | [39, 84] |

| PCS | Adlercreutzia, unclassified Erysipelotrichaceae | NX rats and PCS-induced HK-2 cells | Mediating renal fibrosis and inflammatory cytokines by activating protein kinase C and PI3K signaling pathways. | [39, 84] |

| TMAO | Lachnospiraceae_UCG-002 | CKD and TMAO-induced mice, NX rats, and HK-2 cells | Inducing renal dysfunction and fibrosis by activating AHR/p38MAPK/NF-κB pathway and NLRP3 inflammasome. | [39, 84] |

| IAA | C. bartlettii, C. scatologenes, C. drakei, E. cylindroides, E. rectale, B. thetaiotaomicron, B. fibrisolvens, M. hypermegale, P. distasonis | CKD patients and IAA-induced endothelial cells | Aggravating renal fibrosis and inflammation by activating AHR, p38MAPK, and NF-κB pathways. | [39, 84] |

| Acetate | Akkermansia muciniphila, Blautia hydrogenotrophica | DKD mice, CKD mice, and glomerular mesangial cells | Improving renal fibrosis by reducing the expression of the fibrosis-related genes TGF-β and fibronectin | [89] |

| Propionate | Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens, Megasphera elsdenii, C. catus, Ruminococcus obeum, Roseburia inulinivorans | DKD mice, CKD mice, and podocytes | Attenuating renal inflammation by inhibiting oxidative stress through reducing ROS, NF-κB activation, and the release of MCP-1 and IL-1β. | [89] |

| Butyrate | F. prausnitzii, C. viene, C. eutacus, C. catus, E. rectale, E. hallii, F. prausnitzii | ESRD patients, DKD mice, and HK-2 cells | Attenuating inflammation and renal fibrosis by inhibiting ERK/MAP and NF-κB pathways. | [89, 110] |

| IAld | L. johnsonii | CKD patients, NX and UUO rats, and 1-hydroxypyrene-mediated HK-2 cells | Improving renal function and fibrosis by ameliorating AHR pathway. | [89, 110] |

| HDCA | B. ovatus, C. scindens | UUO and adenine-induced CKD mice | Attenuating renal fibrosis by inhibiting TGF-β/Smad3 and ERK1/2 pathways. | [89, 110] |

| 1,5-AG | B. fragilis | UUO and adenine-induced CKD mice | Improving renal fibrosis by increasing SGLT2 and inhibiting TGF-β/Smad pathway. | [106] |

CKD disrupts the gut microbial equilibrium, establishing a feedback loop that exacerbates disease progression (Figure 2) [24, 33, 65]. Dysbiosis leads to increased levels of uremic toxins and decreased SCFAs (Figure 2) [24, 84]. This dysbiosis is driven by multiple factors, including intestinal urea accumulation, impaired ammonia metabolism secondary to renal dysfunction, dietary modifications, and medical interventions (Figure 2) [35, 111]. The deleterious effects of dysbiosis manifest through three major mechanisms. Impairment of the intestinal barrier facilitates the translocation of bacteria and microbial metabolites, such as IS and LPS, into systemic circulation, inducing endotoxemia (Figure 2) [112]. Dysbiosis increases the production of harmful metabolites such as TMAO, which promotes vascular injury and increases cardiovascular risk [42]. Uremic toxins and pathogen-associated molecular patterns activate the immune system and sustain systemic inflammation (Figure 4) [34]. This complex interplay within the gut-kidney axis not only accelerates renal functional decline, but also diminishes patients' quality of life by altering nutritional metabolism and increasing the incidence of cardiovascular complications [42, 75]. Experimental evidence supports the pathological impact of dysbiosis. Hyperuricemia-induced microbial dysbiosis increases L-kynurenine levels, which activates AHR pathway in renal tissue and promotes fibrosis [113]. Animal studies suggested that beneficial metabolites such as butyrate have been shown to lower blood pressure and reduce inflammation by suppressing the renin-angiotensin system in animal studies [114].

At the cellular level, in vitro studies have revealed that microbial metabolites directly influence kidney cell viability and inflammatory signaling. IS induces cytotoxicity in renal tubular cells by upregulating arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase expression and increasing 12(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid production [115]. IS also enhances the expression of cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A member 1 (CYP1A1), cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily B member 1 (CYP1B1), and inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α) in T cells through activating AHR pathway, as well as modulating inflammatory responses and cell cycle regulation (Figure 3) [84]. Furthermore, IS activates NF-κB signaling, increasing pro-inflammatory factors such as cyclooxygenase-2, ROS, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β, while suppressing antioxidant factors such as heme oxygenase-1 and superoxide dismutase 2, through Nrf2 pathway inhibition, thereby disrupting intestinal homeostasis and promoting systemic inflammation in mice (Figure 3) [116]. Similarly, PCS enhances ROS generation via the protein kinase C and PI3K pathways, leading to elevated inflammatory cytokine expression and renal tubular cell injury (Table 1 and Figure 3) [84]. PCS also induces apoptosis and autophagy by activating NF-κB and MAPK signaling and increasing the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in HK-2 cells (Figure 3) [117]. TMAO further exacerbates renal damage and calcium oxalate deposition by inducing oxidative stress, autophagy, and apoptosis in renal cells (Figure 3) [118]. In summary, CKD-related gut microbial dysbiosis accelerates renal function decline by sustaining a vicious gut-kidney axis cycle that amplifies oxidative stress, inflammation, and metabolic toxicity (Figure 3).

3.2.2. DKD

DKD is one of the most prevalent complications of diabetes mellitus and the leading cause of ESRD worldwide [119, 120]. Emerging evidence indicates that alterations in the gut microbiota composition are closely associated with DKD, and microbial dysbiosis contributes to disease progression [121, 122]. Patients with DKD exhibit a decreased Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio and increased relative abundance of Clostridium [122]. Another study reported elevated relative abundances of Selenomonadales, Neosynechococcus, Shigella, Bilophila, Acidaminococcus, and Escherichia in patients with DKD, whereas non-DKD individuals displayed higher relative abundance of Phlyctochytrium [123]. Further analysis revealed that the relative abundances of Citrobacter farmeri and Syntrophaceticus schinkii were positively correlated with the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio in patients with DKD [123]. These microbial alterations are thought to trigger inflammatory and immune responses by regulating LPS biosynthesis, SCFA production, and carbohydrate metabolism, thereby exacerbating DKD progression (Figure 4) [123]. Du et al. identified increased relative abundances of Megasphaera, Veillonella, Escherichia-Shigella, Anaerostipes, and Haemophilus as potential microbial indicators of DKD [124]. Similarly, Chen et al. reported that the relative abundances of Oscillibacter, Bilophila, UBA1819, Ruminococcaceae UCG-004, Anaerotruncus, and Ruminococcaceae NK4A214 increased in DKD patients compared with non-DKD controls [125]. The overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria not only amplifies host inflammatory responses but also accelerates disease progression [125]. Zhang et al. further demonstrated that the relative abundances of butyrate-producing bacteria, including Clostridium, Eubacterium, and Roseburia intestinalis, as well as potential probiotics such as Lachnospira and Intestinibacter, were decreased in DKD patients, while Bacteroides stercoris abundance was increased [126]. These microbial changes correlated with clinical indicators of lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, and renal function [126]. Dysbiosis-induced disruption of the intestinal barrier aggravates DKD by activating inflammatory responses and reducing SCFA levels (Figure 2 and Figure 4) [126].

Experimental studies using animal models have corroborated these findings. The relative abundances of CAG-352 and Ruminococcus_sp_YE281 were increased in DKD rats, whereas the abundance of Anaerobiospirillum was decreased compared to that in normal controls [127]. In streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic mice, the relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group and norank_f_Muribaculaceae was reduced, while the abundance of Dubosiella increased [128]. Mechanistically, microbial dysbiosis exacerbates renal injury and fibrosis by increasing intestinal permeability, disrupting lipid metabolism, inducing ROS-mediated oxidative stress, and activating TLR4-mediated inflammatory responses (Figure 4) [128]. Furthermore, animal models of DKD show a reduced abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Prevotella, along with increased abundance of Escherichia-Shigella [127, 129]. Although animal models cannot fully replicate human diseases, these findings emphasize the essential role of intestinal flora in the development and progression of DKD. The intestinal microbiota and its metabolites, particularly SCFAs, play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of DKD [130]. Microbial dysbiosis induces oxidative stress, leading to excessive ROS generation, which subsequently activates the NLRP3 inflammasome [92]. This activation triggers inflammation in glomerular endothelial cells and exacerbates renal dysfunction in DKD [92]. Taken together, microbial dysbiosis, activation of RAS, oxidative stress, and inflammation form a complex, interdependent pathophysiological network that drives the onset and progression of DKD.

3.2.3. MN

MN is one of the most common causes of adult nephrotic syndrome and is characterized by the deposition of immune complexes beneath the glomerular basement membrane [40, 131, 132]. Both cationic bovine serum albumin (CBSA)-induced MN rats and idiopathic membranous nephropathy (IMN) patients exhibit a decreased relative abundance of L. johnsonii, Lactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus vaginalis, Lactobacillus murinus, and Bifidobacterium animalis in feces, along with altered serum levels of indole-3-pyruvic acid, IAld, tryptamine, indole-3-lactic acid, and IAA [133]. Further analyses revealed that both CBSA-induced MN rats and IMN patients displayed increased mRNA expression of AHR and its downstream genes CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1, accompanied by decreased cytoplasmic AHR and increased nuclear AHR protein expression in renal tissue (Figure 3) [132]. Additionally, fecal samples from MN patients demonstrated an increased relative abundance of Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Escherichia-Shigella, Subdoligranulum, and Bifidobacterium, together with decreased abundances of Bacteroidota, Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Megamonas, which were associated with MN onset [134]. The relative abundance of Citrobacter and Akkermansia in feces was correlated with clinical serum parameters in patients with MN [135]. These microbial alterations were accompanied by significant changes in the fecal tryptophan metabolism [135].

FMT experiments further demonstrated that gut microbial dysbiosis enhances the intestinal permeability in microbiota-depleted mice and mediates intrarenal activation of NOD-like receptor signaling [135]. Moreover, MN rats exhibited colonic structural injury, an increased Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio, an elevated relative abundance of Allobaculum and Desulfovibrio, greater production of uremic toxin precursors, and reduced levels of SCFAs [136]. These findings deepen our understanding of the intricate interactions between MN and the gut microbiome, providing valuable insights and identifying potential microbial targets for future therapeutic strategies for MN management.

3.2.4. IgAN

IgAN is the most prevalent form of primary glomerulonephritis and has become a major cause of CKD worldwide [131, 137]. A hallmark of IgAN is the accumulation of IgA-containing immune complexes in the glomerular mesangium. IgA, which is predominantly synthesized in the intestinal mucosa, serves as a critical barrier against bacterial pathogens. Alterations in the gut microbiome and its metabolites have been identified as potential factors influencing disease susceptibility and progression [138, 139]. Patients with IgAN exhibit an increased relative abundance of Firmicutes, particularly Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae, along with a reduced abundance of beneficial bacteria, such as Clostridium and Lactobacillus [139]. Furthermore, patients with IgAN display an expansion of the taxonomic chain Proteobacteria-Gammaproteobacteria-Enterobacteriales-Enterobacteriaceae-Escherichia-Shigella, which is reversed following immunosuppressive therapy [140]. This microbial pattern is associated with pathways promoting infectious diseases and xenobiotic metabolism [140]. Among these taxa, Escherichia-Shigella contributes most significantly to the optimal bacterial classifier for distinguishing IgAN [140].

Elevated serum levels of specific metabolites, such as B-cell activating factor, along with increased intestinal permeability and inflammation, further suggest the link between microbial dysbiosis and immune dysregulation [139, 140] (Figure 5). These alterations promote the production of nephrotoxic galactose-deficient IgA1 and exacerbate disease progression [139, 140]. Notably, immunosuppressive therapy not only reduces the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria but also restores gut microbial balance and improves clinical outcomes [139]. In addition, IgAN patients show a decreased relative abundance of Bifidobacterium, which negatively correlates with proteinuria and hematuria levels, suggesting that a reduction in Bifidobacterium abundance is associated with IgAN severity [141]. Probiotic treatment containing Bifidobacterium in IgAN mice alleviates microbial dysbiosis by increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria and reducing the abundance of pathogenic bacteria. Mechanistically, both probiotics and SCFAs ameliorate IgAN manifestations by suppressing the NLRP3/ASC/Caspase-1 signaling pathway [141].

Several studies in IgAN animal models have reported a decreased abundance of beneficial bacteria, including Bifidobacterium, Oscillospira, Roseburia, Turicibacter, and Dubosiella [141-143], along with increased levels of pathogenic bacteria, such as Helicobacter, Alloprevotella, Shigella sonnei, Streptococcus danieliae, Desulfovibrio fairfieldensis, and Candidatus Arthromitus [141, 142]. These alterations are accompanied by diminished microbial diversity indices and abnormal metabolic profiles, including decreased SCFA and polyunsaturated fatty acid levels, indicating a compromised intestinal metabolic state [142]. Studies indicated that microbial dysbiosis in IgAN disrupts intestinal barrier integrity and metabolic balance, leading to the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria and a reduction in beneficial metabolism, thereby upsetting systemic immune homeostasis [142, 143]. This process promotes the formation and deposition of IgA-containing immune complexes in the glomerular mesangial region, thereby triggering inflammation and injury [143]. Furthermore, immunosuppressive therapy improves renal lesions, reverses dysbiosis, and suppresses related inflammatory pathways, revealing the intricate interactions within the microbiome-gut-kidney axis [139]. In summary, microbial dysbiosis is a potential pathogenic factor in IgAN, inducing intestinal dysfunction and triggering systemic immune dysregulation to ultimately cause renal injury.

3.2.5. FSGS

FSGS is a common morphological manifestation of nephrotic, characterized primarily by podocyte injury [144, 145]. Increasing evidence indicates that patients with FSGS exhibit gut microbial dysbiosis [146]. In animal models of nephrotic syndrome, a decrease in gut microbial diversity has been observed, accompanied by a compositional shift from Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes and alterations in specific bacterial taxa that increase the production of precursors for harmful metabolites and uremic toxins [147]. Shi et al. reported that in rats with FSGS, the relative abundances of Bifidobacterium, Collinsella, Paludibacter, Subdoligranulum, Megamonas, and Coprobacter increased, whereas Granulicatella and Christensenella decreased [148]. In addition, in the Adriamycin-induced FSGS model rats, the relative abundances of Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group and Prevotellaceae_UCG-001 were reduced, while [Ruminococcus]_torques_group abundance was increased [149]. Further animal studies have demonstrated that restoring the microbial balance in FSGS rats suppresses pathogenic bacterial proliferation and alleviates renal injury [148]. These findings suggest that the gut microbiota and its metabolites play critical roles in the pathogenesis of FSGS and represent promising targets for future therapeutic interventions.

3.2.6. HN

Hypertension is widely recognized as a critical factor in the pathogenesis of CKD [38]. As a vital endocrine and metabolic organ, the kidney is highly susceptible to hypertensive injury, which contributes to progressive renal dysfunction [150]. Given the complex interactions between the gut microbiome and systemic physiology, dysbiosis, characterized by altered microbial composition and reduced diversity, plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of HN [151]. Wang et al. reported an increased relative abundance of Klebsiella, Turicibacter, and Enterobacter in patients with HN, accompanied by a decreased abundance of Blautia and Clostridium [38]. Furthermore, the abundance of Streptococcus was positively correlated with blood urea nitrogen and proteinuria, whereas Enterobacter abundance was positively correlated with urinary protein levels [38]. These findings suggest that microbial dysbiosis exacerbates renal dysfunction in HN by increasing uremic toxin levels and promoting metabolic disturbances and inflammatory reactions (Figure 2 and Figure 4) [38]. In another study, Qiu et al. found that the relative abundances of Apiotrichum, Cystobasidium, and Saccharomyces were increased in HN patients, whereas those of Bjerkandera, Candida, and Meyerozyma were decreased [151]. The abundance of Apiotrichum and Saccharomyces was positively correlated with renal function, while Saccharomyces, Nakaseomyces, and Septoria were associated with diastolic blood pressure [151]. Further analysis revealed that microbial dysbiosis influences HN progression by modulating immune responses, elevating pro-inflammatory cytokines and TNF-α levels while decreasing anti-inflammatory cytokine concentrations [151]. Yoshifuji et al. demonstrated that compared with sham-operated controls, 5/6 NX rats with hypertension exhibited an increased abundance of Bacteroides and a decreased abundance of Lactobacillus, which correlated with urinary protein excretion [152]. Similarly, animal studies have shown that compared with healthy controls, CKD rats with hypertension displayed decreased abundances of Ligilactobacillus and Ruminococcus but increased abundances of Eubacterium and Duncaniella [153]. Further evidence indicates that microbial dysbiosis exacerbates renal inflammation and accelerates the progression of HN by impairing intestinal barrier integrity and increasing permeability, thereby facilitating the translocation of harmful metabolites, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines and uremic toxins, into the systemic circulation (Figure 2) [152, 153]. These findings suggest that dysbiosis of the gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in HN pathogenesis. A comprehensive investigation of its characteristics and mechanisms may provide valuable insights into novel microbiota-targeted therapeutic strategies for the treatment of HN.

3.2.7. LN

As a major form of glomerulonephritis, LN represents one of the most severe organ manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [37]. Recent studies investigating the association between the gut microbiota and LN have revealed the crucial role of the intestinal microbiome in disease progression and therapeutic response, drawing increasing research attention. Patients with SLE exhibit gut microbial dysbiosis characterized by reduced microbial diversity and elevated serum LPS levels [154]. As LN reflects renal involvement in SLE, it is hypothesized that patients with LN experience similar microbial alterations [155, 156]. Azzouz et al. reported that disease onset in patients is associated with an increased abundance of Ruminococcus gnavus [155]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that symbiotic bacteria can promote LN progression by disrupting intestinal permeability, amplifying systemic inflammation, and activating the immune system (Figure 4) [155, 156]. Mu et al. further observed that LN mice displayed a decreased abundance of Lactobacillales and increased intestinal permeability [157]. Notably, restoration of microbial balance alleviated LN manifestations by reducing B cell infiltration in the kidneys of lupus-prone mice [37]. Animal studies have shown that increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria, such as L. johnsonii and Romboutsia ilealis, and upregulating plasma tryptophan metabolites activate AHR signaling pathway [158]. This activation leads to decreased plasma autoantibody levels, reduced inflammatory cytokine expression, and an overall improvement in LN pathology [158]. In summary, microbial dysbiosis contributes to the onset and progression of LN by disrupting the intestinal barrier integrity and promoting systemic immune activation. Targeted interventions aimed at restoring microbial homeostasis and regulating the associated metabolic pathways may represent promising therapeutic strategies for LN management.

3.2.8. PD and HD

Patients with CKD who progress to ESRD require renal replacement therapies, such as PD and HD [159, 160]. Dialysis treatment significantly alters gut microbial composition and metabolic profiles [161-163]. PD patients exhibited an increased relative abundance of proteolytic bacteria and a decreased abundance of beneficial genera, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium [162, 163]. These alterations reduce the production of SCFAs while increasing the levels of uremic toxins such as PCS and TMAO [162]. In contrast, HD patients displayed an increased relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and serum levels of IS and PCS [163]. Additionally, HD patients showed a reduced abundance of beneficial genera, such as Megamonas, which is responsible for acetate and propionate production [164]. Both dialysis modalities are also associated with disruption of the intestinal barrier integrity, which facilitates the translocation of endotoxins and contributes to systemic inflammation [165]. These findings highlight the complex interplay between gut microbiota, metabolic dysregulation, and systemic health in patients undergoing renal replacement therapy.

3.2.9. Kidney transplantation

Kidney transplantation is regarded as the optimal treatment for ESRD, providing superior survival and quality of life compared with dialysis [10, 166]. However, alterations in the gut microbiota and metabolite profiles have been observed in kidney transplant recipients, particularly in those experiencing antibody-mediated renal allograft rejection or post-transplant diarrhea [167, 168]. Recipients with antibody-mediated rejection exhibit reduced gut microbial richness and diversity, accompanied by significant changes in key metabolites, such as 3β-hydroxy-5-cholic acid and taurocholic acid, both of which correlate strongly with microbial compositional shifts [168]. Furthermore, transplant recipients with post-transplant diarrhea display decreased abundances of beneficial bacteria such as Eubacterium and Ruminococcus, along with increased abundances of pro-inflammatory taxa such as Enterococcus and Escherichia [167]. These microbial changes are associated with alterations in carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, suggesting that diarrhea may result from a dysbiotic state [167]. Together, these findings emphasize the intricate relationship between gut microbiota dysbiosis and metabolic dysfunction in kidney transplant recipients, highlighting the need for microbiome-targeted strategies to improve post-transplant outcomes.

3.3 The transition from AKI to CKD

For patients with AKI, recovery of renal function is a critical determinant of survival and long-term prognosis [169]. Although many patients experience reversible improvement, a substantial proportion continue to exhibit progressive renal decline, ultimately leading to CKD [169]. With increasing recognition of the gut-kidney axis, recent studies have highlighted the pivotal role of gut microbial dysbiosis in the transition from AKI to CKD [169, 170]. For example, in elderly individuals, reduced microbial diversity and decreased abundance of beneficial bacteria lead to lower SCFA levels and increased intestinal permeability [170]. These changes promote low-grade chronic inflammation, thereby facilitating the progression of AKI to CKD [170]. Animal studies have shown that compared with age-matched sham mice, IRI mice exhibit reduced abundance of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium [171]. Concurrently, microbial dysbiosis contributes to persistently elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines during the AKI-to-CKD transition [171]. Zhu et al. reported that IRI-induced AKI mice with gut dysbiosis exhibited reduced SCFA levels and impaired metabolic activity in the renal tubular epithelial cells, which collectively promoted CKD development and renal fibrosis [169]. Similarly, Lee et al. observed that compared with the sham group, mice undergoing the AKI-to-CKD transition displayed decreased abundance of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes [169]. Moreover, gut microbial alterations, such as enrichment of Enterorhabdus, are associated with elevated plasma TMAO levels, leading to exacerbated renal fibrosis and functional decline through activation of oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways (Figure 4) [169]. These findings demonstrate the pivotal role of gut microbiota in mediating the transition from AKI to CKD. Further research into the mechanistic interactions between gut dysbiosis, inflammation, and metabolic reprogramming is essential for understanding kidney disease progression and identifying effective microbiota-targeted therapeutic strategies.

4. Targeting gut microbiota as a promising therapy for the treatment of kidney disease

Numerous studies have demonstrated that gut microbial dysbiosis is intricately involved in the development and progression of kidney disease (Figure 2) [33, 39, 172]. Consequently, targeting gut microbiota has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for treating kidney diseases. Increasing evidence indicates that both AKI and CKD can be ameliorated through several microbiota-directed interventions, including microbial therapeutics (probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics), natural products (traditional Chinese medicines (TCM) and natural compounds), and FMT (Figure 2 and Table 2) [81, 84, 173].

4.1 Reshaping gut microbiota in kidney disease by gut microecological prescription

4.1.1 Remodeling gut microbiota in AKI by microbial therapeutics

The modulation of intestinal microbiota through probiotics, prebiotics, and symbiotic bacteria has emerged as a potential therapeutic approach for managing AKI [170, 174]. A growing body of evidence highlights the importance of maintaining intestinal barrier integrity to prevent the translocation of harmful bacteria and their metabolites into systemic circulation [102]. Probiotics-defined as live microorganisms that confer health benefits on the host-have shown efficacy in protecting against AKI [170, 174]. For instance, Lactobacillus casei Zhang (L. casei Zhang) and P. goldsteinii (Table 2) modulate gut microbiota-derived metabolites and prevent AKI by regulating immune and inflammatory responses (Figure 3) [100, 170]. Furthermore, Pediococcus acidilactici GKA4, its heat-killed form (“death probiotic” GKA4), and postbiotic GKA4 have been shown to mitigate cisplatin-induced AKI by reducing serum biomarkers and renal histopathological injury (Table 2) [100, 174]. These findings highlight the intricate relationship between intestinal health and renal function, suggesting that microbiome modulation can improve the clinical outcomes of patients with AKI [175]. Consequently, targeted combinations of symbiotic bacteria may enhance the intestinal microbial composition, attenuate renal tissue injury, and improve kidney function indicators in AKI.

4.1.2 Reshaping gut microbiota in CKD by microbial therapeutics

Dietary interventions aimed at increasing the production of SCFAs have gained prominence because of the strong correlation between CKD and microbial dysbiosis [176]. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics exert renoprotective effects by modulating the gut-kidney axis, thereby alleviating uremic toxicity and systemic inflammation (Figure 3) [24, 177]. These agents promote the proliferation of beneficial bacteria, while suppressing harmful strains (Table 2) [178, 179]. Clinical studies have demonstrated that probiotic supplementation reduces plasma uremic toxin levels in patients with CKD by increasing beneficial bacteria and decreasing harmful metabolites associated with dysbiosis [180, 181]. For example, supplementation attenuated renal injury by inhibiting AHR pathway through its metabolite IAld in adenine-induced CKD rats (Figure 3) [106]. Similarly, animal studies have shown that probiotics, such as F. prausnitzii, B. ovatus, and B. fragilis, inhibit renal inflammation and fibrosis via multiple molecular mechanisms (Table 2) [107-109]. These include modulation of butyrate-renal GPR43 expression, promotion of intestinal hyodeoxycholic acid synthesis through upregulation of C. scindens, and reduction of LPS while increasing 1,5-anhydroglucitol levels (Figure 3) [107-109]. In addition, treatment with Bifidobacterium animalis A6 has been shown to ameliorate renal fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis by decreasing the relative abundance of toxin-producing species, such as Eggerthella lenta and Fusobacterium, and by reducing serum levels of uremic toxins, creatinine, and urea in CKD rats [110].

Synbiotic supplementation has also been reported to beneficially modulate inflammation, oxidative stress, and lipid metabolism, with evidence demonstrating its efficacy in lowering IS and PCS levels [182, 183]. These effects are mediated through restoration of gut microbial balance and repair of intestinal barrier integrity, thereby reducing the uremic toxin burden and alleviating cardiovascular and metabolic disorders [184]. Animal experiments further support the potential of synbiotics to improve gut microbial composition, reduce uremic toxins, and prevent renal function decline in CKD models [183, 185]. In summary, probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics represent promising therapeutic approaches for CKD management, offering mechanistically grounded interventions targeting the gut-kidney axis.

The effects of gut microecological prescription on gut microbiota, metabolites, and molecular mechanisms in AKI and CKD

| Intervention method | Patients/animal models | Dose | Microbial dysbiosis | Metabolic pathways | Molecular mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. goldsteinii | IRI-induced AKI mice | 1×108 CFU | Increasing P. goldsteinii. | Decreasing LPS level. | Blunting renal injury by reducing inflammation, cell apoptosis, and ROS accumulation. | [100] |

| Pediococcus acidilactici GKA4, etc. | Cisplatin-induced AKI mice | 250 mg/kg | Increasing Pediococcus acidilactici, etc. | Reducing malondialdehyde level, increasing glutathione level. | Alleviating AKI by enhancing activating HO-1/Nrf2 pathway, and mitigating apoptosis and autophagy pathway. | [174] |

| L. casei Zhang | CKD patients, bilateral I/R-induced AKI and CKD mice | 1×109 CFU | Altering Alloprevotella, NK3B31 groups, Allobaculum, etc. | Increasing SCFA and nicotinamide levels. | Improving microbial dysbiosis, intestinal inflammation, promoting kidney repair, and alleviating chronic TIF. | [170] |

| L. johnsonii | Denine-induced CRF rats | 0.2 µL of 1×109 CFU | Increasing L. johnsonii | Increasing IAld levels. | Ameliorating renal fibrosis by restoring microbial dysbiosis and inhibiting AHR pathway via increasing IAld level. | [106] |

| F. Prausnitzii | 5/6 nephrotomy-induced CKD mice | 200 µL of 2×108 CFU | Altering Roseburi, Faecalibacterium, Collinsella, etc. | Increasing butyrate levels, reducing PCS and TMAO levels. | Alleviating renal fibrosis and inflammation by reducing intestinal inflammation and permeability, and upregulating GPR43 expression. | [107] |

| B. ovatus | UUO and adenine-induced CKD mice | 200 µL of 2×108 CFU | Increasing B. ovatus and C. scindens. | Increasing gut HDCA level. | Attenuating renal fibrosis by raising HDCA level, reducing LPS absorption, and inhibiting TGF-β/Smad3 and ERK1/2 pathways. | [108] |

| B. fragilis | UUO and adenine-induced CKD mice | 200 µL of 2×108 CFU | Increasing B. fragilis. | Increasing 1,5-AG level, decreasing LPS level. | Improving renal fibrosis by reducing LPS level, increasing SGLT2, and inhibiting TGF-β/Smad pathway. | [109] |

4.1.3 Regulating gut microbiota in the transition from AKI to CKD by microbial therapeutics

Recently, increasing attention has been directed toward the use of probiotics to modulate disease progression during the transition from AKI to CKD. For example, Zhu et al. reported that the probiotic L. casei Zhang slowed the progression of both AKI and CKD by modulating inflammatory responses in renal tubular epithelial cells and macrophages via gut microbiota-derived metabolites [170]. Animal studies further demonstrated that L. casei Zhang not only enhanced intestinal mucosal barrier integrity and suppressed inflammatory signaling but also exerted renoprotective effects through mechanisms independent of the native microbiota [170]. Kim et al. found that in IRI-induced aged mice, probiotic supplementation with Bifidobacterium bifidum and Bifidobacterium longum reduced the abundance of Parabacteroides and Akkermansia, while increasing the abundance of Alistipes, Muribaculaceae, and Oscillospiraceae [171]. Additional animal studies have confirmed that ameliorating microbial dysbiosis delays the AKI-to-CKD transition by elevating SCFA levels, improving intestinal barrier function, and modulating inflammatory responses [171]. Furthermore, L. casei Zhang mitigated AKI and subsequent chronic renal fibrosis by increasing SCFA and nicotinamide levels and restoring gut microbial homeostasis [186]. In summary, the targeted modulation of microbial dysbiosis during the AKI-to-CKD transition represents an effective strategy to prevent CKD development by enhancing intestinal integrity, reducing inflammation, and promoting metabolic homeostasis.

4.2 Reshaping gut microbiota in kidney disease through natural products

Natural products, including TCMs and plant extracts, have long been used and are widely recognized as important therapeutic interventions for diverse kidney diseases, including AKI and CKD [132, 187, 188]. Recent studies have highlighted the ability of TCMs to modulate the intestinal microbiota and restore metabolic homeostasis in both AKI and CKD (Table 3) [96, 189-191].

4.2.1 Regulating gut microbiota in AKI through natural products

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that natural products can ameliorate AKI by modulating gut microbiota (Table 3) [96, 97]. Zou et al. reported that Qiong-Yu-Gao (QYG), a TCM formula derived from Poria, Ginseng Radix, and Rehmanniae Radix, protects against cisplatin-induced AKI by enhancing the fecal abundance of Akkermansia, Faecalibaculum, and Bifidobacterium [96]. These microbial changes are associated with altered metabolite profiles, including increased acetate and butyrate levels, reduced IS and PCS concentrations, and improvements in AKI biomarkers and indicators of fibrosis and inflammation [96]. Mechanistically, QYG treatment inhibited histone deacetylase expression and activity [96]. The renoprotective effects were abolished following antibiotic-induced microbial depletion but were transferable via FMT, confirming a microbiota-dependent mechanism (Figure 5) [96]. Yang et al. demonstrated that Aconitum carmichaelii Debx attenuates cisplatin-induced AKI by restoring microbial homeostasis, increasing SCFA levels, and decreasing uremic toxins [97]. This restoration was accompanied by the recovery of glutathione and tryptophan metabolism, inhibition of IκB/NF-κB signaling, and activation of Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathways (Figure 5) [97]. Zhu et al. reported that chromone hamaudol, an oxygen-containing heterocyclic compound, ameliorated AKI-associated renal injury by enhancing the abundance of P. goldsteinii [99]. Additionally, Flammulina velutipes polysaccharides (FVP) reduced the abundance of Proteobacteria, Enterococcus, and Shigella while increasing the abundance of Firmicutes, Lactobacillus, Ruminococcus, Bifidobacterium, Lactococcus, Christensenella, and Allobaculum [192]. These microbial shifts were accompanied by elevated SCFA levels, particularly acetate and butyrate [192]. Kidney metabolomic analysis revealed that FVP treatment inhibited ferroptosis by increasing glutathione (GSH), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), and solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) expression while reducing AA accumulation (Figure 5) [192]. These findings illustrate the potential of TCMs and natural products to beneficially modulate the gut-kidney axis, thereby alleviating AKI and potentially preventing its progression to CKD (Figure 5).

4.2.2 Regulating gut microbiota in CKD through natural products

Compared with AKI, a larger body of research has reported that natural products ameliorate CKD by reshaping microbial dysbiosis (Table 3) [189-191, 193]. Liu et al. found that Zicuiyin decoction reduced serum creatinine levels in patients with DKD, accompanied by an increased abundance of Prevotellaceae and Lactobacillaceae and a decreased abundance of Enterobacteriales, Clostridiaceae, and Micrococcaceae (Table 3) [189]. Dong et al. reported that Yi-Shen-Hua-Shi granules, a traditional Chinese patent medicine used to treat patients with CKD, increased the relative abundance of Lachnospiraceae, Sutterella, Lachnoclostridium, and Faecalibacterium, while reducing Eggerthella and Clostridium innocuum group after four months of treatment [190]. Reduction in proteinuria was positively correlated with the abundance of Lachnospiraceae and Lachnoclostridium, suggesting a link with vitamin, lipid, and glycan metabolic pathways (Table 3) [190]. Lin et al. further demonstrated that Fushen granules increased the abundance of Bacteroides, Rothia, and Megamonas, which was correlated with alterations in amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism [193]. These findings indicate that multi-herbal TCM preparations improve renal function in patients with CKD by modulating gut microbiota composition and metabolism.

An expanding number of studies have also emphasized that natural compounds serve as valuable sources for new drug development [194-197]. Our research group demonstrated that treatment with both barleriside A and 5,6,7,8,3',4'-hexamethoxyflavone improved renal function and fibrosis while increasing L. johnsonii abundance in CKD rats (Table 3) [106, 198, 199]. Liu et al. reported that madecassoside, an oxolane-type triterpene glycoside, improves renal function and attenuates fibrosis, while promoting the growth of B. fragilis (Table 3 and Figure 5) [109]. The same group also showed that neohesperidin decreased serum urea and creatinine levels, ameliorated renal fibrosis, and increased B. ovatus abundance in mice with adenine-induced CKD and UUO (Table 3 and Figure 5) [108]. These findings suggest that natural compounds alleviate renal fibrosis through gut microbiome-dependent pathways. Wang et al. further demonstrated that isoquercitrin modulates the microbial electron transport chain, thereby regulating tryptophan transport and indole biosynthesis in adenine-induced CKD mice (Table 3 and Figure 5) [200]. In addition, treatment with coumarins isolated from Hydrangea paniculata improved colonic integrity, decreased the Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes ratio, reduced the relative abundance of Allobaculum and Desulfovibrio, decreased uremic toxin precursors, and enhanced SCFA production in MN rats [136]. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that natural compounds hold great promise as therapeutic agents for kidney diseases (Figure 5).

4.3 Reshaping gut microbiota in kidney disease through FMT

4.3.1 Remodeling gut microbiota in AKI through FMT

FMT represents a novel and promising strategy for reshaping intestinal microbiota in AKI [173]. In experimental models, FMT has been shown to alleviate renal lesions, improve renal function, and reduce inflammatory responses in experimental models [201-203]. Moreover, FMT mitigates the adverse effects of chemotherapeutic nephrotoxicity by restoring intestinal microbial balance and promoting kidney recovery following AKI [203]. These findings suggest that FMT is a promising adjunct therapy for AKI.

4.3.2 Reshaping gut microbiota in CKD through FMT

FMT has also emerged as a promising therapeutic approach for restoring intestinal homeostasis in CKD patients [204-206]. Clinical and preclinical studies have demonstrated that FMT effectively restores microbial diversity and composition, thereby ameliorating microbial dysbiosis [173]. A clinical trial further reported that FMT facilitates the decolonization of multidrug-resistant organisms by replacing resistant strains with beneficial non-extended-spectrum beta-lactamase bacteria, highlighting a potential role for FMT in combating antimicrobial resistance [207]. In addition, FMT has been shown to reduce proteinuria and gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with IgAN and MN, while simultaneously enhancing the production of beneficial metabolites such as SCFAs and reducing levels of harmful uremic toxins [204, 206]. Furthermore, FMT modulates immune responses by counteracting CKD-associated inflammation and metabolic dysfunction [208]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that FMT benefits DKD models by restoring gut microbiota composition, enhancing microbial diversity, and reducing tubulointerstitial injury and inflammatory cytokines [209]. The study also emphasized the critical role of acetate-producing gut flora and their metabolites in mediating the metabolic and inflammatory balance [209].

The effects of natural products on gut microbiota, metabolites, and molecular mechanisms in AKI and CKD

| Intervention method | Patients/animal model | Dose | Microbial dysbiosis | Metabolic pathways | Molecular mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aconitum carmichaelii Debx | Cisplatin-induced AKI mice | 5, 10 mg/kg | Altering Ligilactobacillus, Bacteroides, Escherichia-Shigella, etc. | Increasing SCFA levels, decreasing uremic toxins, and kynurenic acid levels. | Alleviated AKI by inhibiting NF-κB and promoting Nrf2/HO-1 signalling pathways. | [97] |

| FVP | Cisplatin-induced AKI mice | 50, 100, 200 mg/kg | Increasing Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, Shigella, etc. | Increasing SCFA level, decreasing AA level. | Retarding renal fibrosis by inhibiting ferroptosis via increasing GSH, GPX4, and SLC7A11 expression. | [192] |

| Hamaudol | IRI-induced AKI mice | 30 mg/kg | Increasing P. goldsteinii | Decreasing LPS level. | Improving renal injury by retarding intestinal barrier, renal inflammation, and cell apoptosis. | [100] |

| Qiong-Yu-Gao | Cisplatin-induced AKI mice | 7 g/kg | Increasing Faecalibaculum and Bifidobacterium, decreasing Lactobacillus, and Bacteroides | Increasing SCFA level, reducing uremic toxin level. | Improved renal fibrosis by suppressing histone deacetylase expression and activity. | [96] |

| Zicuiyin decoction | DKD patients | 75 g/100 ml | Altering Lactobacillaceae, Enterobacteriales, Clostridiaceae, etc. | Increasing SCFA level, decreasing creatinine level. | Improving kidney function by ameliorating gut microbiota and relieving persistent albuminuria. | [189] |

| Yi-Shen-Hua-Shi Granules | CKD patients | 3 bags/day | Altering Bacteroides, Sutterella, Clostridium innocuum group, etc. | Increasing SCFA level. | Mitigating CKD by regulating metabolism of polysaccharides, lipids, and vitamins via altering gut microbiota. | [190] |

| Suyin Detoxification granules | CKD rats | 3.3, 6.6 g/kg | Increasing Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, and Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group | Decreasing serum TMAO level. | Mitigating CKD by affecting lipid metabolism and renal tubular ferroptosis. | [211] |

| Yiqi-Huoxue-Jiangzhuo formula | NX mice | 23.6, 11.8, 5.9 g/kg | Increasing Lachnospiraceae-NK4A136-group but decreasing Eubacterium-nodatum-group | Decreasing serum TMAO level | Mitigated renal injury and exerted cardiac protective effects by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome. | [212] |

| BSA and HMF | Adenine-induced CKD rats | 10 mg/kg | Increasing L. johnsonii | Increasing IAld level. | Improved renal fibrosis by inhibiting profibrotic protein expression. | [106] |

| Neohesperidin | UUO and adenine-induced CKD mice | 50 mg/kg | Increasing B. ovatus | Increasing HDCA level. | Retarding renal fibrosis by increasing Bacteroides ovatus. | [108] |

| Madecassoside | UUO and adenine-induced CKD mice | 80 mg/kg | Increasing B. fragilis | Increasing 1,5-AG level. | Retarding renal fibrosis by increasing B. fragilis, inhibiting oxidative stress, and TGF-β/Smad pathway. | [109] |

| Isoquercitrin | Adenine-induced CKD mice | 80 mg/kg | Decreasing E. coli | Decreasing IS level. | Blunting CKD by inhibiting tryptophan transport and indole synthesis via gut bacteria. | [200] |

| Moutan cortex polysaccharides | high-sugar diet and STZ-induced DKD rats | 80, 160 mg/kg | Altering Akkermansia, Ruminococcus, Ruminococcus_2, etc. | Increasing SCFA level but decreasing branched-chain fatty acids and LPS levels. | Mitigating renal injury by reducing pro-inflammatory mediators and increasing SCFA. | [213] |

| Paotianxiong polysaccharides | Adenine-induced CKD rats | 62.5, 125, 250 mg/kg | Altering B. fragilis, L. murinus, L. animalis, and P. aeruginosa | Decreasing stearic acid, linoleic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid levels. | Improving kidney damage by regulating unsaturated fatty acid metabolism and reducing inflammatory factors. | [214] |

| Astragalus membranaceus and Salvia miltiorrhiza | DKD rats | 2.95, 5.9 g/kg | Altering Akkermansia_muciniphila, Lactobacillus, Lactobacillus_murinus | Decreasing IS and PCS levels. | improving DKD by inhibiting inflammation and regulating glucose and lipid metabolism. | [127] |

Impact of microbial dysbiosis on inflammatory response and immune system. Microbial dysbiosis leads to the accumulation of uremic toxins and LPS, which affect the immune system and inflammatory response via two pathways. Harmful metabolites interact with intestinal epithelial cells, leading to activation of NF-κB signaling pathway. Harmful metabolites cross the gut intestinal barrier, activate immune cells, including dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, leading to inflammatory reactions. Harmful metabolites also promote antigen presentation and initiate host adaptive immune responses by affecting the inflammatory factors. Microbial dysbiosis exacerbates renal fibrosis by increasing the levels of uremic toxins and LPS and by regulating the immune system and inflammatory response.

Comprehensive effects of natural products on kidney diseases by regulating gut microbiota. Natural products, including TCMs and plant extracts, are important therapies for intervening in diverse kidney diseases, including AKI and CKD. They retard renal fibrosis in a gut microbiome-dependent pathway. They attenuated AKI by increasing levels of SCFAs and decreasing levels of LPS, inhibiting NF-κB and TGF-β/Smad signaling pathways, and upregulating GSH, GPX4, and SLC7A11 expression. They improved renal fibrosis and inflammation by increasing levels of SCFAs and IAld, decreasing levels of uremic toxins, inhibiting TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway, as well as inflammatory factors, reducing tryptophan transport and indole synthesis.

Additional evidence indicates that FMT effectively mitigates microbial dysbiosis and reduces circulating uremic toxins, including p-cresyl glucuronide and PCS, which are strongly associated with CKD progression [210]. Taken together, these findings support FMT as an emerging therapeutic modality that not only restores microbial equilibrium but may also slow CKD progression through multi-target modulation of metabolic, inflammatory, and immune pathways.

5. Conclusion and challenges

Growing evidence supports a reciprocal relationship between the host and the intestinal microbiome across various kidney diseases. Further studies are critically needed to delineate the distinct features of the gut microbiome in kidney disorders and clarify its specific associations with different renal pathologies. Intestinal inflammation and compromised epithelial barrier integrity accelerate the systemic dissemination of bacterially derived uremic toxins such as IS, PCS, and TMAO, which induce oxidative stress and cause progressive renal damage. Recent research on the gut-kidney axis has revealed novel therapeutic pathways to alleviate inflammation, renal injury, and uremia, thereby preventing adverse clinical outcomes in CKD (Figure 2). Multiple promising strategies have been proposed to restore gut microbial equilibrium and slow the progression of kidney diseases. Approaches such as gut microecological prescriptions and TCM formulations provide innovative, signaling-directed interventions that may surpass conventional pharmacotherapies, often burdened by adverse effects. Moreover, the selection of probiotic strains with well-defined metabolic and immunomodulatory functions has the potential to mitigate diverse renal pathologies (Figure 2). Future studies should rigorously evaluate these interventions in large-scale clinical trials to translate microbiome-based strategies into tangible clinical benefits for CKD patients. Mounting evidence has identified key microorganisms, microbial enzymes, and metabolites as potential therapeutic targets. An enhanced grasp of host-microbiome metabolic interactions will pave the way for developing innovative probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics, facilitating the emergence of personalized, microbiota-targeted therapies for preventing and treating kidney diseases.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82474062, 82274192 and 82274079) and Shaanxi Key Science and Technology Plan Project (No. 2023-ZDLSF-26).

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Abbad L, Esteve E, Chatziantoniou C. Advances and challenges in kidney fibrosis therapeutics. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2025;21:314-29

2. Ndongo M, Nehemie LM, Coundoul B, Diouara AAM, Seck SM. Prevalence and outcomes of polycystic kidney disease in African populations: a systematic review. World J Nephrol. 2024;13:90402

3. Blum MF, Neuen BL, Grams ME. Risk-directed management of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2025;21:287-98

4. Zarbock A, Forni LG, Ostermann M, Ronco C, Bagshaw SM, Mehta RL. et al. Designing acute kidney injury clinical trials. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024;20:137-46

5. Hukriede NA, Soranno DE, Sander V, Perreau T, Starr MC, Yuen PST. et al. Experimental models of acute kidney injury for translational research. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18:277-93

6. Meng XM, Wang L, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. Innate immune cells in acute and chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2025;21:464-82

7. Allinson CS, Pollock CA, Chen X. Mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the AKI-to-CKD transition. Integr Med Nephrol Androl. 2023;10:e00014

8. Huang MJ, Ji YW, Chen JW, Li D, Zhou T, Qi P. et al. Targeted VEGFA therapy in regulating early acute kidney injury and late fibrosis. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44:1815-25

9. Araji G, Keesari PR, Chowdhry V, Valsechi Diaz J, Afif S, Diab W. et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency in dialysis patients: risk factors, diagnosis, complications, and treatment: a comprehensive review. World J Nephrol. 2024;13:100268

10. Basile G, Pecoraro A, Gallioli A, Territo A, Berquin C, Robalino J. et al. Robotic kidney transplantation. Nat Rev Urol. 2024;21:521-33

11. Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Wang AYM, Kalyesubula R, Schaeffner E, Agarwal R. Epidemiology and risk of cardiovascular disease in populations with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18:696-707

12. Luyckx VA, Al Aly Z, Bello AK, Bellorin Font E, Carlini RG, Fabian J. et al. Sustainable development goals relevant to kidney health: an update on progress. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17:15-32

13. Khandpur S, Mishra P, Mishra S, Tiwari S. Challenges in predictive modelling of chronic kidney disease: a narrative review. World J Nephrol. 2024;13:97214

14. Zhao BR, Hu XR, Wang WD, Zhou Y. Cardiorenal syndrome: clinical diagnosis, molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2025;46:1539-55

15. Nakazawa D, Masuda S, Nishibata Y, WatanabeKusunoki K, Tomaru U, Ishizu A. Neutrophils and NETs in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2025;21:383-98

16. Yang X, Bayliss G, Zhuang S. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and current treatments. Integr Med Nephrol Androl. 2024;11:e24-00011

17. Anders HJ, Huber TB, Isermann B, Schiffer M. CKD in diabetes: diabetic kidney disease versus nondiabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:361-77

18. Youhua L. Kidney fibrosis: fundamental questions, challenges, and perspectives. Integr Med Nephrol Androl. 2024;11:e24-00027

19. Jafry NH, Manan S, Rashid R, Mubarak M. Clinicopathological features and medium-term outcomes of histologic variants of primary focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in adults: a retrospective study. World J Nephrol. 2024;13:88028

20. Balakumar P. Unleashing the pathological role of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in diabetic nephropathy: the intricate connection with multifaceted mechanism. World J Nephrol. 2024;13:95410

21. De Gregorio V, Barua M, Lennon R. Collagen formation, function and role in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2025;21:200-15

22. Agarwal R, Verma A, Georgianos PI. Diuretics in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2025;21:264-78

23. Kishi S, Nagasu H, Kidokoro K, Kashihara N. Oxidative stress and the role of redox signalling in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024;20:101-19

24. Krukowski H, Valkenburg S, Madella AM, Garssen J, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Overbeek SA. et al. Gut microbiome studies in CKD: opportunities, pitfalls and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19:87-101

25. Cao G, Miao H, Wang YN, Chen DQ, Wu XQ, Chen L. et al. Intrarenal 1-methoxypyrene, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist, mediates progressive tubulointerstitial fibrosis in mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022;43:2929-45

26. Chia ZJ, Cao YN, Little PJ, Kamato D. Transforming growth factor-β receptors: versatile mechanisms of ligand activation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2024;45:1337-48

27. Miao H, Wang YN, Su W, Zou L, Zhuang SG, Yu XY. et al. Sirtuin 6 protects against podocyte injury by blocking the renin-angiotensin system by inhibiting the Wnt1/β-catenin pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;45:137-49

28. Miguel V, Shaw IW, Kramann R. Metabolism at the crossroads of inflammation and fibrosis in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2025;21:39-56

29. Wang YN, Zhang ZH, Liu HJ, Guo ZY, Zou L, Zhang YM. et al. Integrative phosphatidylcholine metabolism through phospholipase A2 in rats with chronic kidney disease. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44:393-405