Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(4):1693-1716. doi:10.7150/ijbs.127929 This issue Cite

Review

Targeting Lysosomes for Enhanced Anti-Cancer Therapeutics and Immune Response

The Fred Wyszkowski Cancer Research Laboratory, Faculty of Biology, The Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 3200003, Israel.

Received 2025-11-5; Accepted 2026-1-6; Published 2026-1-15

Abstract

Cancer is a leading cause of death in Western countries. Apart from surgical resection, the primary treatment modalities chemotherapy and radiotherapy inflict serious side effects, and significantly remodel both tumor metabolism and the tumor microenvironment. This consequently compromises treatment efficacy, resulting in multiple drug resistance, immune evasion and cancer progression. Lysosomes are unique acidic intracellular organelles crucial for maintaining cellular health and homeostasis via degradation of cellular waste. Lysosomes are also required for autophagy, a stress-induced catabolic pathway that is important for cell survival. Autophagy is typically enhanced in tumor cells, as it can confer cyto-protection against the deleterious cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy, and suppress anti-cancer immune response. Owing to their acidic nature and their role in endocytosis, lysosomes can be readily targeted and manipulated, thus attenuating the autophagic flux and improving cancer treatment outcome. Herein we focused on various classic and innovative lysosome modulators, their impact on autophagy, the enhancement of immune response, and consequent inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis. We discuss modalities to minimize adverse effects in cancer patients by either utilizing harmless compounds, achieving synergistic activity with combination therapies, or specifically targeting the tumor by using advanced nanoparticle technologies.

Keywords: lysosomes, LMP, autophagy, macrophage, immune response

Introduction

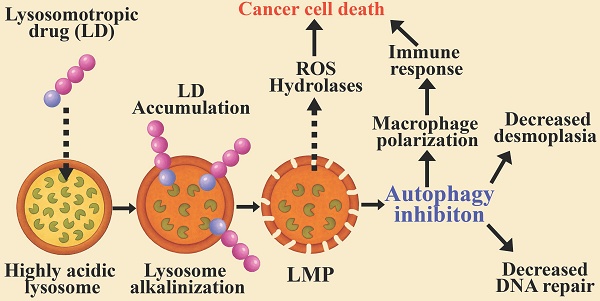

Lysosomes are eukaryotic membrane-bound cellular organelles with an acidic lumen at a pH range of 4.5-5.5 [1-4], containing approximately 60 hydrolytic enzymes [5] displaying optimal activity at acidic pH [6-8]. These hydrolytic enzymes, including proteases, nucleases, lipases, glycosidases, phospholipases, phosphatases, and sulfatases, are responsible for the degradation of proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, glycosides, and cellular debris, including damaged organelles, thereby maintaining cellular health and homeostasis [9-12]. Apart from their major degradative role, lysosomes are central sensory hubs which respond to multiple cues to regulate metabolism, cell differentiation and division, as well as apoptosis and tumorigenesis [13-16]. Furthermore, lysosomes are key components and regulators of the homeostatic autophagy process [17-19]. The latter involves the sequestration of damaged organelles, misfolded proteins, intracellular pathogens and other foreign substances in double-membrane vesicles known as autophagosomes, which fuse with lysosomes for cargo degradation and recycling (Figure 1) [20-22]. Autophagy promotes either cell survival or cell death [23-27]. As a stress-induced catabolic pathway, autophagy facilitates the adaptation of cells to stress conditions such as starvation, by breaking down damaged or non-essential cellular structures and macromolecules to provide essential metabolites [28,29]. Mitochondrial damage triggers mitophagy (mitochondrial autophagy), by which it protects the cell against release of pro-apoptotic proteins and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [30]. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, following accumulation of unfolded proteins can lead to ROS generation and cell death [31,32]. Autophagy provides cyto-protection by degrading damaged ER, thereby attenuating ER-stress defense and apoptosis [33]. Moreover, autophagy can induce anti-cancer drug resistance via several molecular mechanisms which were previously reviewed [34-36]. Enhanced autophagy protects cancer cells from DNA damage [37-39], in part, by the timely degradation of proteins of the DNA damage repair (DDR) system, such as checkpoint kinase 1 (CHEK1) [40,41]. This timely degradation prevents excessive retention of DDR proteins on damaged/repaired chromatin loci, allowing for their replacement by subsequent factors necessary for the next step in the DNA repair pathway. Hence, autophagy promotes enhanced DDR in cancer cells during treatment with DNA damaging modalities, such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) [42] and radiation therapy [43,44]. Given the key role that autophagy plays in cancer development, progression and survival [35,45-48], concentrated efforts were focused on developing novel strategies for the inhibition of autophagy during cancer therapy [49-53]. This development requires efficient assays for monitoring the autophagy steps (Figure 1), to identify and quantify autophagy inhibition [54,55].

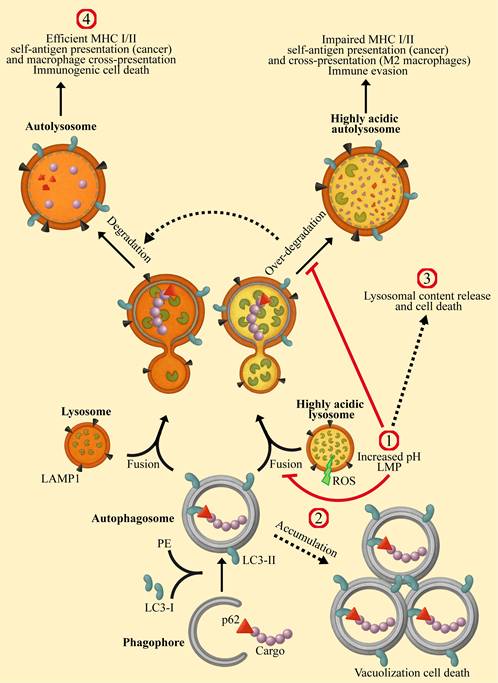

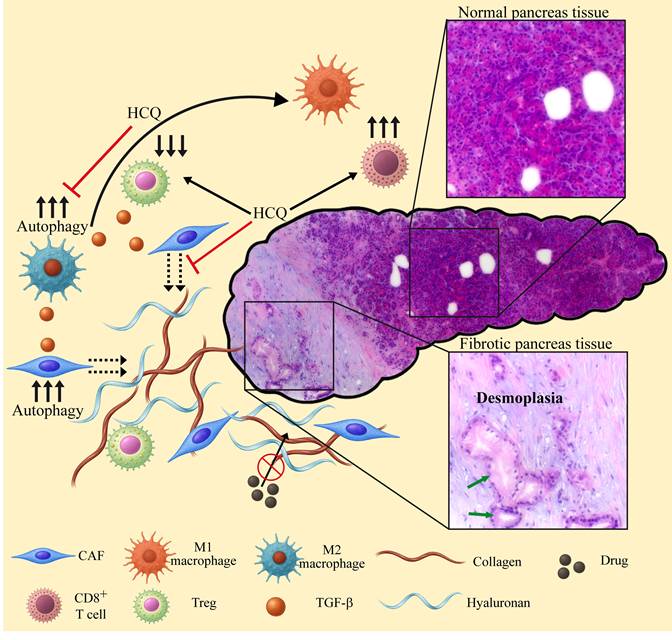

Modulating the enhanced autophagy in cancer cells via lysosomal targeting. The autophagy process is initiated by the formation of a cap shaped, double-membraned phagophore, which expands and elongates to capture cytoplasmic cargo. The cargo is tagged by ubiquitin-binding protein p62 (Sequestosome-1). Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha (LC3) is recruited to the phagophore membrane through phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) lipidation to form a double-membrane autophagosome, decorated with LC3-II. This autophagosome fuses with a lysosome to form an autolysosome, in which the cargo and membrane proteins are degraded. The lysosomes of cancer cells and M2-macrophages are highly acidic, with increased activity of hydrolases. This results in over processing of the digested cargo, thereby preventing cancer antigen presentation, culminating in immune evasion. Lysosomotropic drugs (LDs) affect autophagy at the indicated sites: 1) Lysosomal alkalinization by CQ, HCQ, Naphplatin, hydrotalcite, TFP, and BCZT leads to LMP. Conversely, treatment with ginsenosides Ro and Rh2, UIOQM-IQ, Lys05, and Ir-C3N5 induces LMP, resulting in lysosomal alkalinization. Both alkalinization and LMP can inhibit autophagosome-lysosome fusion and/or decrease degradation within autolysosomes, resulting in autophagy inhibition. 2) Inhibiting autophagosome-lysosome fusion results in the accumulation and enlargement of autophagosomes, leading to vacuolization cell death. 3) LMP mediates the release of lysosomal content to the cytosol, including ROS and hydrolytic enzymes, triggering mitochondrial depolarization and lysosomal cell death. 4) Lysosomal alkalinization decreases the activity of hydrolases, thereby reducing degradation of MHC and antigen molecules within autolysosomes. This potentiates immunity by enhancing self-antigen presentation on cancer cells and cross-presentation by macrophages.

Lysosomal targeting can be achieved using lysosomotropic drugs (LDs), primarily characterized by their hydrophobic weakly basic nature, which allows them to freely diffuse into cells and intracellular organelles [56-58]. LDs diffuse in and out of the cellular membranous compartments, however, once they encounter the acidic lumen of the lysosome, they undergo protonation, become cationic and can no longer traverse the membrane. This results in their intercalation and accumulation within the lysosomes' membranes [59-61]. This sequestration “sink” effect results in the accumulation of LDs in lysosomes at concentrations which are 1000-2500-fold higher than their extracellular drug concentrations within a few hours [62]. From a mechanistic perspective, concentrated positively charged molecules at the water-interface of the membrane bilayer disrupt the electrostatic balance between the lipid headgroups, inducing repulsion between the choline groups of phospholipids and increasing the distance between neighbor lipids [59]. This can lead to membrane fluidization [63-66] and lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) [67]. The utility of lysosomal protons (H+) for the protonation process and loss of protons following LMP, alkalinizes the lysosomal luminal pH [68,69]. Lysosomal targeting can also be achieved by utilizing the endocytic pathway [70].

In this review we focus on strategies, from the last decade, for lysosomal targeting, leading to the induction of lysosomal dysfunction, LMP, lysosomal rupture and lysosomal cell death (LCD), with emphasis on autophagy inhibition, and immunogenic cell death (ICD). We discuss lysosomal targeting with single agents and in combination with other drugs (i.e., chemotherapeutics) or bona fide therapy modalities (i.e., radiotherapy and sonodynamic therapy) for the eradication of cancer cells and tumors. While targeting lysosomes with photosensitizers for efficient photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a rapidly growing research field, it has been widely reviewed in recent years [71-78] and hence will not be discussed herein.

Targeting lysosomes for anti-tumor immune response

Macrophage polarization

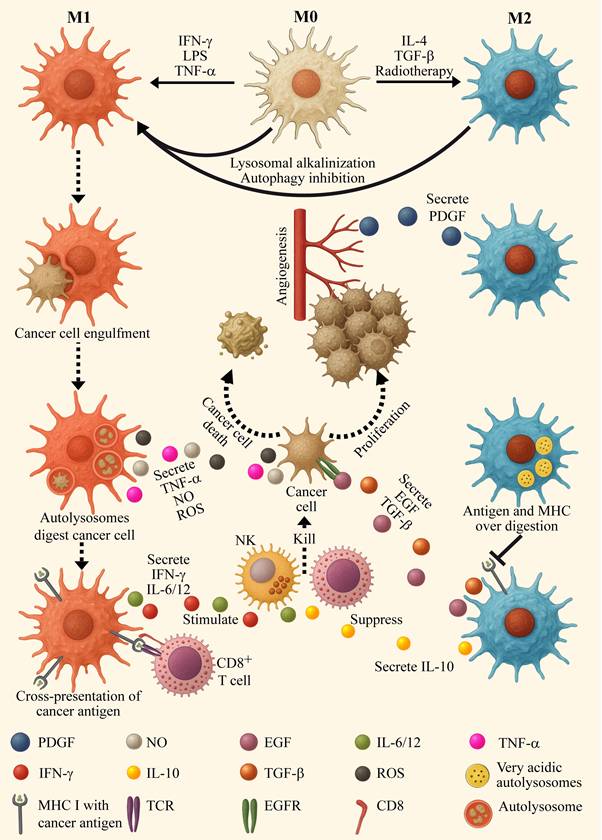

Macrophages are the predominant immune cell population present in cancer tissues [79,80]. While macrophages have tumor-cell killing capacities, most experimental and clinical reports describe macrophages as protumor cells attenuating antitumor immune responses [81-84]. Following macrophage polarization, they assume two main phenotypes designated M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory) depicted in Figure 2 [81-85]. M1 macrophages are stimulated by interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and toll like receptor (TLR) ligands, including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and lipoteichoic acid (LTA). Following stimulation, they express high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and IFN-γ, as well as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [86]. While M1 macrophages eliminate malignant cells, they also promote the antitumor cytotoxic activity of other leukocytes. Their enhanced tumor antigen presenting ability activates cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs, killer T cells, CD8+ T cells), and the cytokines they secrete stimulate and boost the function of natural killer (NK) cells.

In contrast, protumoral M2 macrophages act as immune suppressors [87]. They have an impaired tumor antigen presentation ability, and secrete anti-inflammatory suppressor factors such as IL-10, hence negating any antitumor immune response. Furthermore, M2 macrophages release tumor promoting growth factors, such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), thereby encouraging tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis and metastasis [81-85]. Collectively, high prevalence of M2 tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) predicts dismal prognosis in various cancers, including lung [88], breast [89], pancreatic [90], and prostate cancer [91]. It is well established that one of the most paramount characteristics that distinguishes between M1 and M2 macrophages is their lysosomal status. Lysosomes of M2 macrophages are more acidic than those of their M1 counterparts (pH ~4.5 vs ~5.3, respectively) [92-94]. This affects the degradation process of biomolecules within the lysosomal lumen and the phagocytotic cascade, since many lysosomal proteases possess acidic pH optima below 4.5 [6]. M2 lysosomes display elevated hydrolase activity [95,96], leading to enhanced degradation of proteins (as well as lipids and nucleic acids), resulting in excessive antigen processing and diminished peptide presentation by MHC [97,98]. This enhanced lysosomal activity also promotes an elevated autophagic flux in M2 macrophages [99,100].

In this respect, autophagy promotes lysosomal degradation of MHC I, thereby decreasing cancer-related antigen presentation, and facilitating immune evasion [101,102]. Alkalinization of lysosomal pH with chloroquine (CQ) [101] or bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) [102] attenuated both the lysosomal enzymatic activity and the autophagic flux, resulting in higher surface presentation of MHC-I and an improved immune response against pancreatic cancer. This was also demonstrated by inhibiting the activity of the lysosomal protease cathepsin B (CTSB) [103].

Effectors of macrophage polarization and characteristics of the macrophage phenotypes. On the left side, M0 resting macrophages undergo polarization to the pro-inflammatory/anti-tumoral M1 phenotype by microbial agonists of toll-like receptors, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), as well as the cytokines interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), which are then secreted by M1 macrophages themselves. The latter engulf and digest cancer cells via phagocytosis and autophagy. Lysosomes of M1 macrophages display relatively high pH for lysosomes (~5.3) and low hydrolase activity, resulting is moderate autophagy flux and cargo digestion. This results in optimal cancer-antigen sizes for cross presentation on MHC I, which then activates CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells. M1 macrophages secrete nitric oxide (NO), ROS and TNFα which elicit cancer cell death via apoptosis and necrosis. M1 macrophages activate and stimulate cytotoxic immune cells, including CD8+ T-cells and natural killer cells (NKs), by secreting pro-inflammatory interleukins including IL-6 and IL-12 as well as IFN-γ. On the right side: M0 resting macrophages undergo polarization to the anti-inflammatory/pro-tumoral M2 phenotype by naturally secreted IL-4 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) as well as by radiotherapy (and other anti-cancer treatment modalities). M2 macrophages secrete pro-tumoral growth factors, such as platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), which promote angiogenesis, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and TGF-β that induce cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion. M2 lysosomes present with high acidity (pH~4.5) and enhanced hydrolytic activity. This leads to the over-processing of cargos through the autophagy system, resulting in low cancer-antigen cross-presentation, facilitating immune evasion. M2 macrophages actively suppress the activity of CD8+ T-cells and NKs by secreting anti-inflammatory interleukins such as IL-10.

Strategies are being developed to convert M2 to M1 macrophages, many of which utilize compounds that attenuate the lysosomal acidity and enzymatic activity. Naphplatin, a conjugation product of cisplatin to the core of the topoisomerase II inhibitor amonafide [104], was shown to localize in lysosomes of macrophages and increase their luminal pH [94]. In turn, lysosomal alkalinization promoted the release of Ca+2 via the lysosomal cation channel mucolipin (Mcoln1), resulting in activation of the MAPK p38 signaling pathway. This led to the transformation of bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) and M2-BMDMs to the pro-inflammatory M1-phenotype [94]. In mice transplanted with murine colorectal cancer (CRC) CT-26 cells, treatment with cisplatin monotherapy induced an immune-suppressive response by increasing the percentage of tumoral M2 macrophages to 40% (p < 0.01). In contrast, naphplatin decreased the tumoral M2 macrophage population below 5%, while increasing the M1 population to ~80% (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively). This change was accompanied by a ~50% decrease in the levels of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the tumor, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the blood, further alleviating immune suppression. Naphplatin treatment boosted TAMs to inhibit CRC growth (final tumor weight was 10% of control) and pulmonary metastasis in CT-26 cells bearing mice, resulting in an 82.7% increase in survival time. To assess the contribution of macrophages to the anti-tumor effect of naphplatin, mice were also pretreated with the macrophage depleting agent clodronate [105], which abolishes mitochondrial ATP generation via inhibition of mitochondrial ADP/ATP translocase leading to apoptotic cell death. Pretreatment with clodronate diminished the anti-tumor effect of naphplatin, resulting in only 35% reduction in tumor weight. These findings establish the importance of lysosomal alkalinization to the immune response [94].

The same mechanism of increased lysosomal pH, consequent Ca+2 release and activation of MAPK p38 was demonstrated following treatment of mouse BMDMs and human macrophages with CQ [92]. M2-TAMs were converted to the M1 phenotype, resulting in tumor growth inhibition and prolonged survival of B16 melanoma-bearing mice. Furthermore, following CQ treatment, mouse models of lung metastasis displayed a decreased number of tumor nodules in the lungs, and H22 hepatocarcinoma malignant ascites mouse models displayed reduced volume of ascites as well as reduced number of tumor cells [92].

pH-gated nanoparticles (PGNs) that self-assemble from amphiphilic copolymers were designed to accumulate within- and distinguish between lysosomes of M2-like BMDMs and other cell types, based on subtle lysosomal pH deviations [93]. When conjugated to the TLR7/8 agonist imidazoquinoline (IQ), the now termed pH-gated nanoadjuvant (PGN4.9) selectively increased lysosomal pH in M2 macrophages, decreased cathepsin activity and converted these cells to the M1-phenotype. This in turn increased antigen presentation and activation of CTLs, resulting in tumor regression in a mouse 4T1 breast cancer model and further circumvented the formation of lung metastasis [93].

Yue Chen et al., took a different approach by harnessing the increased expression/activity of CTSB in tumor cells [106-109] and M2 macrophages [95,110] to ignite a newly designed lysosomal “nanorocket” [111]. The latter, termed UIOQM-IQ, consists of an ultrasmall iron oxide (UIO) nanoparticle (NP) conjugated to a CTSB-cleavable peptide, an aggregation-induced emission fluorophore QMTPA, and surface IQ. Following IQ-dependent endocytosis and internalization into lysosomes, CTSB cleaves the peptide within UIOQM, thus releasing QMTPA and UIO NPs with exposed -NH2 and -SH termini which drive cross-linking and aggregation of both QMTPA and UIO NPs. Both aggregates allow tumor visualization, with QMTPA activating a fluorescent “on” switch, and UIO inducing a distinct MRI contrast shift, enabling deep-tissue imaging. Most importantly however, the bulky UIO aggregates within lysosomes lead to elevated osmotic pressure, and consequent LMP [111]. LMP can lead to lysosomal alkalinization and dysfunction, or to the release of lysosomal content into the cytosol, leading to LCD [112,113]. The former will result in autophagy inhibition and macrophage polarization, and the latter should release cancer specific antigens and elicit an immune response. In fact, LMP is regarded as a mechanism driving ICD which triggers an intact antigen-specific adaptive immune response [114,115]. Murine mammary carcinoma 4T1 cells express higher levels of CTSB than normal 3T3 murine fibroblast cells [111,116], hence UIOQM-IQ elicited a specific cytotoxic effect on 4T1 but not on 3T3 cells (surviving fractions ~20% and > 90%, respectively) [111]. In vivo evaluation of UIOQM-IQ was conducted using 4T1 cells bearing mice. The lysosomal “nanorocket” promoted a robust anti-tumor immune response, represented by a remarkable increase in M1:M2 macrophage ratio from ~2 to > 30 (p < 0.0001), > 4-fold increase in secretion of TNFα and IFN-γ as well as IL-6 and IL-12. Moreover, an increase in the percentage of mature dendritic cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes (TDLN), and an increase in infiltrating CTLs was also noted, along with a decrease in the levels of Tregs. The combination of the anti-tumor immune response and the cytotoxic effect of UIOQM-IQ resulted in 5-fold smaller tumors and longer survival time (~35 days vs. > 60 days for control and UIOQM-IQ treated mice, respectively). Notably, UIOQM-IQ reduced lung metastases by ~8-fold [111].

E64-DNA, a DNA nanodevice composed of the small-molecule cysteine protease inhibitor, E-64 (Figure 3) [117], conjugated to a 38-base pair DNA duplex, was developed to selectively enter TAMs via endocytosis and accumulate within their lysosomes. Once there, E64-DNA inhibited lysosomal-specific cysteine proteases which are elevated in M2-TAMs, thereby increasing the cells' ability for antigen cross- presentation and effective CTL activation [95]. When E64-DNA was combined with the widely used alkylating chemotherapeutic cyclophosphamide [118], sustained tumor regression was achieved in a triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) mouse model [95].

Panax ginseng ginsenosides

In an effort to potentiate anti-tumor immunity with minimal chemotherapy-inflicted adverse effects, as well as to improve the quality of life of cancer patients, strategies are being developed for the combined treatment of herbal agents along with chemotherapy [119-122]. One of the most commonly used roots that has been subjected to extensive anti-cancer research is ginseng, primarily its pharmacologically active constituents ginsenosides [123-127].

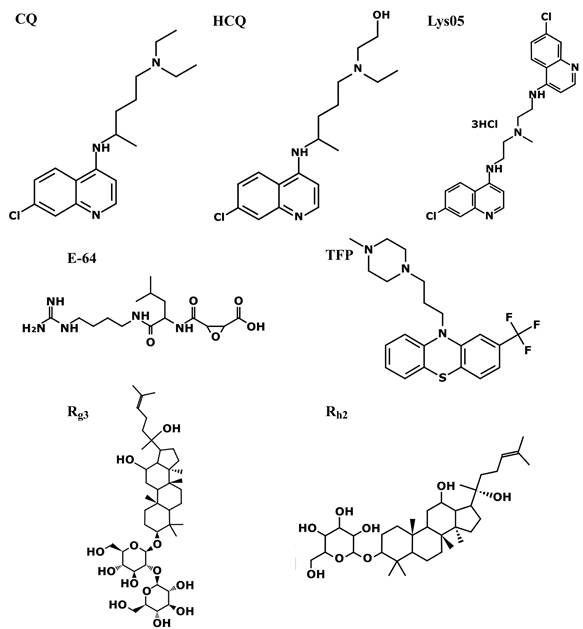

Ginsenosides are triterpene saponins (Figure 3), which include major ginsenosides and their secondary metabolic derivatives [128], of which Rg3 [129,130] and its deglycosylated derivative Rh2 [131,132], exhibit the most beneficial biological activities in various human pathologies. Regarding the present review, various ginsenosides were shown to increase lysosomal pH [42,133], induce LMP [133,134], inhibit autophagy flux [42,133,135-138], and enhance immunity [126,139-141]. These resulted in sensitization to chemotherapy/immunotherapy [42,135,137-139,142,143], and most importantly enhanced in vivo anti-tumor activity [136,139,141,143,144].

Structures of various LDs described in the current review. The anti-malarial drug chloroquine (CQ), its derivative hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), and its bisaminoquinoline dimeric form Lys05. The irreversible and selective cysteine protease inhibitor E-64. The antipsychotic phenothiazine trifluoperazine (TFP). One of the primary pharmacologically active constituents of ginseng, ginsenoside Rg3 and its deglycosylated derivative Rh2. Excluding ginsenosides, all molecules have hydrophobic rings and a hydrophilic amine group which undergoes protonation in acidic lysosomes, leading to their lysosomal accumulation, where they elicit lysosomal alkaliniziation and/or LMP. The ginsenosides act by triggering LMP by increasing cytosolic ROS levels. The molecules were generated using PubChem Sketcher V2.4.

It should be emphasized that although ginsenosides affect lysosomal function, they are not LDs according to their physicochemical properties, endowing them with both low water solubility and poor membrane permeability [145]. Ginsenosides Ro [146,147] and Rh2 were shown to increase cytosolic ROS levels in cancer cells, either via the estrogen receptor 2 (ESR2)-neutrophil cytosolic factor 1 (NCF1)-ROS axis [42], or mitochondrial ROS production [133]. Extralysosomal ROS can damage the lysosomal membrane, and induce LMP with consequent lysosomal alkalinization, as was demonstrated upon mitochondrial ROS generation [148,149]. This was also the case with Ro and Rh2 [42,133,134]. As abovementioned, lysosomal alkalinization reduces the activity of resident hydrolases; consistently, treatment with Ro reduced the activity of CTSB and CTSD [42]. Lysosomal alkalinization can also inhibit autophagosome-lysosome fusion [150]. Both decreased lysosomal enzymatic activity and autophagosome-lysosome fusion result in a reduction in the autophagic flux, as was observed following Ro or Rh2 treatment [42,133]. The ability of ginsenoside Rh2 to inhibit autophagy was utilized to reverse the phenotype of RAW264.7 derived M2 macrophages to the M1 subtype in vitro [140]. While an Rh2 liposome (Rh2-lipo), where Rh2 functioned both as a cholesterol substitute membrane stabilizer, and a chemotherapy adjuvant, successfully polarized macrophages to the M1 phenotype in vivo [141]. The increase in M1 macrophages in an orthotopic breast cancer 4T1 tumor bearing mouse model injected with Rh2-lipo, was accompanied by residual levels of IL-10 and consequently high levels of activated CTLs and a dramatic decline in Tregs. The resulting potentiation of the immune response led to a 40% decrease in tumor volume, an impact which was enhanced to 80% via the co-encapsulation of Rh2 with paclitaxel (PTX) [141]. Utilizing Rh2 as a component of the liposome membrane allowed tumor targeting via the glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) which recognizes ginsenosides as substrates [151], and is overexpressed in tumors [152].

Ginsenoside Rg3, another late-stage autophagy inhibitor [137,138], was also incorporated as a cholesterol substitute in the membrane of liposomes (Rg3-LPs) [139]. In this study, the affinity of ginsenoside-liposomes for GLUT1 was exploited to both penetrate the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), and deliver PTX for the targeted eradication of C6 glioma brain tumors in both mice and rat models. Rg3-LPs, and to a greater extent Rg3-PTX-LPs, polarized M2 macrophages to the M1 phenotype, both in vitro and in vivo, along with an 80% decline in the levels of TGF-β. The immune activation in the tumor microenvironment (TME) drastically reduced the presence of MDSCs and Tregs, while increased the abundance of CTLs from 5% to 30-40%. Collectively, these favorable activities dramatically increased the survival of C6 glioma bearing mice from 21 days to 32 and 54 days for Rg3-LPs and Rg3-PTX-LPs, respectively (p < 0.01). In the rat model, the survival was even longer, with the Rg3-PTX-LPs group exceeding the experiment time of 60 days [139].

A systematic review analyzed the impact of combining first-line chemotherapy with the ginsenoside Rg3 in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [153]. Analysis of 2,200 NSCLC patients from China revealed excellent results highlighting the beneficial effects of Rg3 for cancer patients. When compared to the control group receiving first-line chemotherapy alone, the Rg3 supplemented patients exhibited higher response rates (p < 0.00001), higher Karnofsky performance status index (p < 0.00001), higher one- and two-year survival rates (p = 0.01, p = 0.006), higher rate of weight improvement (p = 0.02), reduced VEGF levels (p = 0.02), less gastrointestinal adverse effects (p = 0.02) as well as lower rates of myelosuppression (p < 0.00001) [153]. An additional review analyzed the benefits of ginsenosides Rh2, Rg3 and compound K [154,155] as adjuvant therapy in 1,448 hepatocellular carcinoma patients, demonstrating similar remarkable results [156]. It should be conveyed, that since ginsenosides display pleiotropic activities [129-132], the beneficial effects they elicit as adjuvants cannot be solely attributed to their lysosomotropic effects.

Radiotherapy

Radiation therapy aka radiotherapy (RDT) is an established hallmark of cancer treatment, along with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, hormone therapy, and surgery [157-159]. RDT employs high-energy ionizing radiation in order to elicit two major antitumor activities [160,161]. The first is the obvious eradication of the irradiated target cells by inducing DNA damage, mitotic catastrophe and apoptosis [162]. The second, is referred to as in situ tumor vaccination [163,164] which stimulates a systemic immune-mediated antitumor response. Following RDT-induced cell death, the local release of tumor-derived antigens promotes their cross-presentation by various antigen presenting cells (APCs), which in turn instigates an immediate and prolonged immune response via the activation of NK cells, CTLs and B-cells [165-168]. This “vaccination” can elicit an abscopal effect, where irradiation of a small tumor area induces a systemic antitumor immune response throughout the body, resulting in regression of tumors in remote, untreated parts of the body [169-171]. Inasmuch as this sounds promising, RDT is actually effective in only a fraction of cancer cases, while in others it has the exact opposite effect. In this respect, various studies have shown that following RDT, a burst in immune-suppressive stimuli occurs [162], leading amongst others, to an elevation in pro-tumoral M2 macrophages [162,172,173]. Moreover, using the lung colonization model of transplanted murine 4T1 breast cancer cells, RDT was shown to enhance lung metastasis in mice [173,174], and the pro-metastatic impact required the presence of macrophages [174]. Although studies have shown that lysosomes and autophagy are main contributors to this RDT-resistance [159,175,176], only a few studies have attempted to target lysosomes to overcome this radioresistance.

A very recent study that targeted lysosomes, followed the example of successfully enhancing immunotherapy by alkalinizing the lysosomes of macrophages, and implemented this strategy following RDT treatment [173]. Using the mouse 4T1 orthotopic breast cancer model, Bei Li et al., demonstrated that an immune-suppressive TME was established following RDT. This included a high prevalence of M2 macrophages and poor tumor infiltration of CTLs [173]. Post-RDT macrophages were stimulated with cytidine monophosphate guanosine oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG), a TLR 9 agonist, resulting in the rewiring of their central carbon metabolism. This promoted these macrophages to engulf and eradicate tumor cells for antigen cross-presentation [177]. However, since M2 macrophages have extremely acidic lysosomes with enhanced hydrolytic activity, as mentioned above, the antigens were over-processed, abolishing antigen-presentation by MHC I. Thus, the authors administered a MgAl-based hydrotalcite (bLDH) alkaline nanoadjuvant to the peritumoral area post-RDT. Hydrotalcite is an antacid currently used to neutralize stomach acidity [178,179]. While the combination of CpG and bLDH was sufficient to increase surface localization of antigen presenting MHC I in macrophages, the effect was even stronger post RDT. A previous study with hydrotalcite-embedded magnetite NPs, showed the accumulation of these NPs in lysosomes [180]. Consistently, bLDH induced lysosomal alkalinization in BMDMs. The enhanced cross-presentation following co-administration of CpG and bLDH resulted in priming of antigen-specific CTLs and tumor infiltrating NKs leading to the consequent suppression of the primary tumor and lung metastasis in the mouse 4T1 breast tumor model [173].

The brain tumor glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is a highly aggressive and fulminant malignancy which displays immune-evasion [181], chemoresistance and radioresistance [182,183]. In the latter respect, to surmount this RDT resistance, Xin Zhang et al., utilized trifluoperazine (TFP, Figure 3) [184], an antipsychotic phenothiazine from the 1950s [185]. TFP has been shown to inhibit proliferation, migration, and invasion of GBM cells, however it failed to extend the survival time of orthotopic U87MG xenograft bearing mice [186]. In contrast, when combined with RDT, TFP significantly increased the survival of orthotopic xenograft GBM mouse models with P3 cells (median survival 46.0 vs 29.7 days for combined treatment vs. radiation alone, p < 0.01) [184]. TFP is a highly hydrophobic weak base compound [187], like the majority of anti-psychotic drugs, and thus highly accumulates in lysosomes [59,188]. Indeed, Xin Zhang et al., demonstrated lysosomal alkalinization following treatment with TFP, along with a decrease in the activity of lysosomal cathepsin proteases, and a consequent decrease in the autophagic flux [184]. In a follow up paper, this group further revealed that TFP induced lysosomal swelling and LMP, resulting in reduction of the autophagic flux [189]. However, the radio-sensitization achieved by TFP was attributed to impaired homologous recombination during radiation-induced DDR, with no mention of abrogating RDT-induced immune-suppressive responses [184].

Qi Xu et al., developed a core-shell copper selenide-coated gold (Au@Cu2-xSe) NPs which were shown to minimally affect lysosomal pH, and to prominently block the autophagic flux [190]. This resulted in radio-sensitization and tumor eradication, leading to prolonged survival of orthotopic mouse xenograft GBM model harboring human U-87MG cells (median survival 42 vs 29 days, for combined Au@CS + X-Ray treatment vs. X-Ray alone) [190]. These NPs required focused ultrasound (US) to better traverse the BBB and reach the intracranial tumor site.

Chloroquine

The anti-malarial drug CQ (Figure 3) has been widely studied in the treatment of various pathological disorders [191] including cancer [192,193]. Its lysosomotropic properties have been exploited for lysosome alkalinization (as discussed in the immunotherapy chapter) and autophagy inhibition [194]. These properties have also been exploited to sensitize tumors to RDT, primarily GBM.

Glioma initiating cells (GICs) [195] are radio-chemo-resistant stem-like cells responsible for relapse following treatment of GBM with RDT [196,197]. Early studies demonstrated that enhanced autophagy promotes differentiation of GICs [198], decreases their tumorigenicity [199] and restores their radio-sensitivity [200]. In contrast, in recent years, autophagy inhibitors were shown to increase sensitivity of GICs to both RDT [201] and chemotherapy [202]. Chenguang Li et al., settled the dispute by showing that inhibition of autophagy at different stages of the process has distinct effects [203]. Blocking the autophagic flux at the end of the process, i.e., autophagosome-lysosome fusion and/or content degradation, leads to the accumulation of degradative vacuoles, and resensitizes GBM cells to anti-cancer treatments.

Autophagy inhibition by CQ at the stage of autophagosome-lysosome fusion [194] potentiated the radio-sensitivity of GICs isolated from the human glioma cell line U87 [201]. The combination of CQ and X-ray markedly decreased the clonogenic surviving fraction of GICs by ~10-fold compared to X-ray alone, and increased apoptosis by a factor of > 2-fold. Finally, the combination exhibited a synergistic activity on GICs generated tumor spheres, decreasing both their numbers and diameters [201].

The potential of CQ in restoring radio-sensitivity to GBM has been tested in several clinical trials over the past 20 years with encouraging outcomes (Table S1) [204-209]. When presenting increased progression free survival (PFS) and median survival time after surgery for CQ-treated patients, it emerged that these clinical trials could have been the initiators of routine CQ administration in GBM treatment. However, the patient numbers in all these trials were too small to attain statistical significance and draw definitive conclusions. For example, the Sotelo group published the results of a prospective controlled randomized trial, where nine patients receiving an additional daily dose of 150-mg CQ to the radiochemotherapy, were compared to nine control patients. The mean survival time was 31±5 and 10.6±2 months, respectively, p<0.0002 [204]. Later, the same group published a post-surgery median survival time of 24 months for CQ-treated patients (n=15) and 11 months for control patients (n=15), with double the number of survivors in the CQ-treated patients at the end of observation (p = 0.139) [205]. Furthermore, a study on the treatment of recurrent GBM (rGBM), retrospectively compared 33 patients in a control group receiving only adjuvant-radiochemotherapy (aRCT) to those receiving aRCT+ bevacizumab (BEV, n = 5) or the triple combination: aRCT+BEV+CQ (n = 4). Median post recurrence survival times were 9.63, 12.97 and 23.92 months, respectively, p = 0.022 [209].

Some beneficial effects were clinically attributed to the addition of CQ in combination with standard chemotherapy, in case of advanced or metastatic anthracycline-refractory breast cancer [210] and metastatic or unresectable pancreatic cancer [211] (Table S1). The maximal tolerable CQ dose in clinical trials was found to be 200-250 mg/day [208,209,212]. Higher doses of CQ elicited multiple adverse effects, including irreversible blurred vision and vomiting [208]. Although CQ is an excellent lysosomal alkalinizing agent, its tolerable dose might not be sufficient to allow for effective autophagy inhibition required for chemo/radio/immuno-sensitization. One plausible modality to circumvent these adverse effects of high dose CQ is its encapsulation and tumor targeting [213].

CQ encapsulation

Temozolomide (TMZ), a DNA alkylating and methylating agent, is the first-line chemotherapeutic drug in the treatment of GBM and anaplastic astrocytoma [214,215]. However, like most cytotoxic drugs, TMZ inflicts adverse effects with up to 20% of glioma patients suffering from thrombocytopenia [216]. The combination of TMZ and CQ has been shown to bear a synergistic effect in eradicating GBM cells [217,218], primarily via lysosomal dysfunction and autophagy modulation [218]. Furthermore, this combination displayed promising results in clinical trials [205,208]. Hence, the combined encapsulation of these drugs in targeted NPs has the potential to exert synergistic anti-tumor effects without harming healthy tissues.

Mesoporous silica NPs (MSNs) have been extensively used experimentally for drug delivery in vivo [219]. The incorporation of polydopamine (PDA) into MSNs allows to modify the surface of the NPs and attach specific ligands for cancer targeting [220]. PDA also adds a pH-responsive element to the NPs as it undergoes degradation under acidic conditions, enhancing drug release in lysosomes or in the acidic TME [221,222]. The arginyl-glycyl-aspartic acid (RGD) tripeptide [223,224] is an established ligand of αvβ3 integrin used for in vivo tumor mapping and targeting [225-227]. The surface integrin αvβ3 is crucial for tumor angiogenesis and is highly expressed predominantly in new blood vessels [228,229], as well as various tumors [230-234] including GBM [230,235]. TMZ and CQ were co-loaded into MSNs coated with PDA decorated with RGD, designated TMZ/CQ@MSN-RGD [236]. In vitro growth inhibition assays, using the αvβ3 integrin expressing human GBM cell line U87 [237], showed a 4-fold lower IC50 value for TMZ/CQ@MSN-RGD compared to free TMZ (24.5 vs. 104.3 µg/ml, respectively), while TMZ/CQ@MSN-RGD had little effect (< 15%) on the viability of rat cortical neuronal cells, even at a high concentration of 1 mg/ml. These results suggest the specificity of the NPs for GBM cells. By accumulating in lysosomes (following endocytosis), inhibiting autophagy, and enhancing apoptosis, TMZ/CQ@MSN-RGD inhibited tumor growth in U87 cells xenograft bearing mice, twice as much as free TMZ, with no apparent toxicity to healthy organs [236].

A cyclic RGD peptide was also used to coat lipid NPs (LNPs) co-loaded with CQ and the anti-malarial drug dihydroartemisinin (DHA) [238]. Apart from integrin αvβ3 being a target, RGD is also an established ligand of integrin αvβ6 [224,239,240], which is highly overexpressed in CRC, where it enhances tumor aggressiveness [241-244]. DHA is considered a sensitizing agent shown to increase ROS levels in cancer cells [245-247], however, its pharmacologic effect as a single agent is usually abrogated by the activation of protective autophagy [248-250]. Hence, it was determined that DHA should be combined with other cytotoxic agents [251], preferably an autophagy inhibitor [252,253]. This was the rational for the design of LNPs co-loaded with CQ and DHA and decorated with RGD (RLNP/DC) for the treatment of CRC [238]. Even when loaded with a relatively low CQ concentration of 7.5 µM, RLNP/DC exhibited superior potency in inhibiting colony formation, increasing ROS production, inhibiting autophagy, and increasing apoptosis in CRC HCT116 cells compared to free CQ+DHA. The results obtained from in vitro invasion and migration assays suggested an anti-metastatic potential for RLNP/DC. Consistently in vivo, murine HCT116 cell models of CRC and metastasis, presented with ~3-fold less CRC tumors, which were ~3-fold smaller upon treatment with RLNP/DC, compared to free CQ+DHA. RLNP/DC-treated mice also developed half the number of liver metastases than those treated with free drugs, and exhibited a 25% increase in survival rates, with all mice being alive at the end of the 60 days experiment. RLNP/DC-treated mice also maintained the highest body weight throughout the experiment [238].

Encapsulation of hydroxychloroquine

The devastating pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [254,255] has a unique TME characterized by hyperactivated stromal fibroblasts, effective immunosuppression, and an elevated dense extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition known as desmoplasia [256] (Figure 4). This physical barrier, promoted by high levels of autophagy [257-259], limits the delivery and efficacy of chemotherapy [260] and immunotherapy [261], while autophagy supports immune evasion [101,102]. Drug encapsulation has been tested to help penetrate this dense desmoplastic ECM barrier and target stromal cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and tumor cells [262,263]. PDAC cells overexpress integrins αvβ6 [264] and αvβ3 [234,265] and thus are good targets for RGD-decorated NPs. The CQ derivative hydroxychloroquine (HCQ, Figure 3) has similar lysosomotropic properties and anti-cancer modes of action to CQ by alkalinizing lysosomes and inhibiting autophagy [193,266]. HCQ has been shown to be ~40% less toxic in animals [267] and have less adverse effects in humans [268], and has been clinically explored in the treatment of PDAC (Table S1) [269-274]. For example, pre-operative treatment of PDAC patients with gemcitabine and HCQ markedly increased the overall survival in patients who had a > 51% increase in the autophagy marker LC3-II in circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (34.8 vs. 10.8 months, p < 0.05) [275]. Moreover, HCQ was shown to possess antifibrotic activity, by reducing collagen levels and inhibiting ECM synthesis in 4T1 mouse tumor models [258]. These findings led to the design of TR-PTX/HCQ-Lip, liposome-based NPs decorated with a multifunctional tandem peptide TH-RGD (TR), loaded with a combination of HCQ and PTX [276]. TR consists of a targeting cyclic RGD tripeptide and a pH-responsive cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) [277]. CPP should become protonated under the acidic pH of the TME, thus converting its charge from negative to positive and facilitating its membrane penetration by electrostatic forces, particularly between the positive charge of the CPP and the negatively charged polar head groups of membrane phospholipids [278,279]. This enhances the RGD-based specificity of the liposomes to tumors. The ability of TR-PTX/HCQ-Lip to penetrate the dense fibrotic stroma and target the PDAC tumor was verified using a murine BxPC-3/NIH 3T3 heterogenous pancreatic tumor model [276]. The heterogenous tumor model consisting of both CAFs and tumor cells is utilized to mimic the complex PDAC architecture and desmoplastic components [280]. In comparison with free HCQ and non-targeted HCQ-containing NPs (PEG-HCQ-Lip, PEG-PTX/HCQ-Lip), TR-PTX/HCQ-Lip completely disrupted lysosomal accumulation of Lysotracker, and robustly inhibited autophagy in BxPC-3 and NIH 3T3 cells [276]. Autophagy inhibition and reduction in ECM deposition were also verified in vivo in harvested tumors. Moreover, TR-PTX/HCQ-Lip was superior in inhibiting migration and invasion of BxPC-3 cells. In an orthotopic BxPC-3 tumor bearing mouse model, administration of free PTX+HCQ had little effect on tumor growth, eliciting a reduction of ~15% in tumor growth. In contrast, TR-PTX/HCQ-Lip exerted a dramatic growth inhibitory effect, resulting in an ~85% reduced tumor weight (p < 0.001). Consistent results were obtained with the heterogenous tumor mouse model, suggesting good response by CAFs. Moreover, TR-PTX/HCQ-Lip completely eliminated any surface liver metastases, compared to 50-90 metastatic nodules on livers of mice treated with free PTX+HCQ (p < 0.001) [276]. In accord with the loss of body weight as a hallmark of PDAC [281], all orthotopic BxPC-3 tumor bearing mice exhibited weight loss with disease progression, while those treated with TR-PTX/HCQ-Lip largely retained their original weight. Importantly, the encapsulation of PTX and HCQ prevented hepatic toxicity induced by the free drugs [276]. Collectively, these findings reveal a good response to HCQ as a drug adjuvant, and the advantages of drug encapsulation and tumor targeting.

The role of autophagy and inhibition of autophagy in reprograming the TME and TIME of PDAC. High levels of autophagy in cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) promote the secretion of ECM components including collagen and hyaluronan. High levels of autophagy in macrophages result in an M2 phenotype, leading to the secretion of TGF-β. The latter further increases autophagy in TME cells, enhances ECM stiffness and stimulates cancer cell proliferation. The dense desmoplastic barrier prevents accessibility of various anti-cancer drugs to the tumor cells. M2 macrophages suppress anti-tumor immune responses, stimulating the differentiation of Tregs that further suppress the immune system. Lysosomotropic drugs like HCQ, block autophagy, thereby reprogramming the TME and TIME as follows: 1) M2 macrophages undergo polarization to the M1 phenotype, thus stimulating the activity of CTLs, reducing the levels of Tregs and TGF-β. 2) The secretion of collagen and hyaluronan by CAFs is halted, thereby preventing the biosynthesis of new ECM. Consequently, the desmoplastic barrier is relieved, restoring the accessibility of anti-cancer drugs to the tumor cells as well as the infiltration of active immune cells. The normal and fibrotic pancreatic tissues shown are representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) histopathological staining performed on a biopsy derived from a patient during the initial diagnosis of PDAC. The slide was scanned using a Leica DMI8 inverted fluorescence microscope. Morphologically abnormal ducts lined with cancerous cells (green arrows) are surrounded by a desmoplastic environment (pale purple staining).

Taking advantage of autophagy a step further, Yang Wang et al., decided to not only prevent the beneficial impacts of autophagy in tumors, but to also use autophagy as a tumor killing approach. By both enhancing the first step and inhibiting the last stage of autophagy, the researchers induced autophagic catastrophic vacuolization and death of both tumor cells in vitro and mouse tumor models in vivo [282]. This was achieved by utilizing a TAT-Beclin 1 peptide (T-B) along with HCQ-loaded liposomes (HCQ-Lip). The T-B peptide consists of the transduction domain of the CPP TAT protein, linked to the HIV-1 Nef-binding domain of Beclin 1 required to initiate autophagy [283]. Indeed, inducing the generation of autophagosomes by T-B and preventing their fusion with lysosomes via HCQ-Lip, led to the overwhelming synergistic accumulation of autophagosomes (6-7-fold over free HCQ or T-B) in four different tumor cell lines. This led to 95% apoptosis/necrosis of cancer cells [282]. Treatment of 4T1 xenograft-bearing BALB/C mice with an intra-tumoral injection of T-B and an intravenous injection of HCQ-Lip resulted in ~90% smaller tumors than in the control group (p < 0.001), which were 3.3-fold smaller than those of mice treated with each component alone (p < 0.001). Examination of the resected tumors revealed vast autophagic vacuolization and necrotic areas at the center of the tumors [282]. Since HCQ is less toxic than CQ, all currently ongoing clinical trials, utilizing autophagy inhibitors to improve the outcome of cancer therapy, include HCQ (Table 1).

Lys05

A CQ derivative that has gained much interest is Lys05 (Figure 3), a bisaminoquinoline dimeric form of CQ which is 10-fold more efficacious as an autophagy inhibitor than HCQ in human GBM LN229 cells [284]. At high doses, Lys05 is such a potent autophagy inhibitor, that it elicited in mice an intestinal phenotype resembling genetic defects in the autophagy gene ATG16L1 [284]. Unlike HCQ, Lys05 was shown to have single-agent antitumor activity without untoward toxicity in mice bearing HT-29 CRC xenografts at low doses (i.e., 10 mg/kg and 40 mg/kg), hence achieving the goal of preventing adverse effects [284]. The mode of action of Lys05 was demonstrated using the GBM U251 and LN229 cell lines [44]. Following its accumulation in lysosomes, Lys05 induced LMP, resulting in lysosomal alkalinization and content release, resulting in mitochondrial depolarization and tumor cell death. While Lys05-induced lysosomal dysfunction did not prevent the fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes, the degradation within autolysosomes was impaired, hence inhibiting the autophagy flux [44]. In accord with the immune-suppressive effects of irradiation detailed above, irradiation of U251 and LN229 cells resulted in increased CTSB activity. In this respect, Lys05 was shown to robustly enhance the cytotoxic effect of irradiation in vitro via LMP and elevated irradiation-induced DNA damage [44].

Overcoming resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have truly revolutionized the treatment of human malignancies [285-287]. However, the efficacy of cancer treatment with TKIs has been hampered by the frequent emergence of multiple mechanisms of TKI resistance [288-290]. In this respect, various TKIs are hydrophobic weak bases which highly accumulate in lysosomes, thereby being sequestered away from their kinase target [291,292]. In fact, many TKIs were shown to enhance protective autophagy [293-299] which constitutes a major resistance mechanism [293,298].

Ongoing clinical trials using a lysosome disrupting agent as an autophagy inhibitor to enhance cancer treatment outcome. All clinical trials utilized hydroxychloroquine in addition to the base therapy.

| Clinical trial | Cancer type | Base therapy mode | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I/II | Solid tumors | Combinations of metformin, sirolimus, dasatanib, nelfinavir | NCT05036226 |

| Phase II | Refractory solid tumors | Devimistat and 5-Fluorouracil or gemcitabine | NCT05733000 |

| Phase I | Advanced solid tumors | MK2206 (highly selective AKT inhibitor) | NCT01480154 |

| Proof of principle | Prostate cancer | A placebo-controlled study | NCT06408298 |

| Phase II | Serous ovarian cancer | Nelfinavir mesylate, bevacizumab | NCT06971744 |

| Interventional | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Chemotherapy and radiotherapy pretreatment | NCT06389201 |

| Phase I/II | Recurrent brain tumors | Dabrafenib and/or trametinib | NCT04201457 |

| Phase I/II | PDAC | mFOLFIRINOX | NCT04911816 |

| Phase 0/I | PDAC | Paricalcitol and losartan | NCT05365893 |

| Phase II | Metastatic PDAC | Trametinib | NCT05518110 |

| Phase I | Metastatic PDAC | Trametinib | NCT03825289 |

| Phase I | Metastatic PDAC | Chlorphenesin Carbamate and mFOLFIRINOX | NCT05083780 |

| Phase II | Metastatic PDAC | Paricalcitol, gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel | NCT04524702 |

| Phase II | Advanced NSCLC | Erlotinib | NCT00977470 |

| Phase II | Metastatic CRC | 5-Fluorouracil, irinotecan and bevacizumab | NCT05843188 |

| Phase II | Metastatic CRC | Encorafenib and cetuximab or panitumumab | NCT05576896 |

| Phase I/II | Recurrent osteosarcoma | Gemcitabine and docetaxel | NCT03598595 |

| Phase I/II | Metastatic melanoma | Nivolumab or nivolumab/ipilimumab | NCT04464759 |

| Phase I/II | Advanced breast cancer | Trastuzumab deruxtecan or sacituzumab govitecan | NCT06328387 |

| Phase II | Dormant breast cancer | Palbociclib | NCT04841148 |

| Phase II | Dormant breast cancer | Everolimus | NCT03032406 |

Abbreviations: CRC: colorectal cancer. mFOLFIRINOX: modified FOLFIRINOX using 80% of drug doses; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Clear cell ovarian carcinoma (CCOC) is a subtype of ovarian cancer characterized by intrinsic chemoresistance, including to established TKIs [300,301]. Sunitinib, a small-molecule multi-targeted TKI [302,303], initially elicited a good response in two CCOC patients [304], but had little effect in a clinical trial [305]. A suggested mechanism of sunitinib resistance was its accumulation and sequestration in lysosomes [306-308], a mechanism that could be exploited for LCD by PDT [309,310]. At low concentrations, sunitinib was shown to impair autophagy, however at clinically relevant cytotoxic drug levels, sunitinib increased the autophagy flux [294,295]. Thus, several studies have shown the benefit of combining sunitinib treatment with an autophagy inhibitor [311-314], as was the case with CCOC [315]. The combination of sunitinib and Lys05 exerted a synergistic growth inhibitory effect on three CCOC cell lines compared to each drug alone; an effect that was recapitulated by combining sunitinib with autophagy protein 5 (ATG5) siRNA. The effect of the combined treatment was further explored in vivo in heterotopic murine models bearing the human CCOC cells TOV21G and OVTOKO. Mice receiving this combination treatment exhibited a substantial reduction of 45% (p < 0.01) and 54% (p < 0.0001) in tumor growth compared with mice treated with monotherapy of sunitinib or Lys05, respectively [315].

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is successfully treated with TKIs including imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib and the newer TKI asciminib [316,317]. However, leukemic stem cells (LSCs) are insensitive to TKIs and persist as a minimal residual disease (MRD) source, resulting in relapse [318-320]. In this respect, inhibition of autophagy has been shown to sensitize CML cells to TKIs [321,322]. Using a CML patient-derived xenograft model, Pablo Baquero et al., showed that hematopoietic LSCs exhibit an increased autophagic flux compared to non-leukemic cells [323]. Remarkably, treatment of these leukemic mice with Lys05 resulted in autophagy inhibition, while HCQ had no inhibitory effect. The latter results were recapitulated in stem cell-enriched (CD34+) cells isolated from CML patients. Lys05 induced autophagy inhibition, which reduced LSCs quiescence and promoted myeloid cell expansion and maturation in the CML mouse model [323]. Lastly, the combination of Lys05 and nilotinib, a second generation TKI [324,325] that was shown to induce autophagy [296,297], resulted in a significant additive therapeutic effect by reducing the fraction of human CD45+ cells in the bone marrow of these CML mouse model (p = 0.05), while HCQ had no additive pharmacological effect [323]. CD45 is a pan-leukocyte marker expressed on nearly all hematopoietic cells, including hematopoietic stem cells [326].

The most common type of leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), accounts for ~33% of newly diagnosed leukemias in the US [327,328]. Survival of CLL cells relies on B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling [329,330], which is conveyed through various kinases, including the pivotal Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) [331,332]. While the TKI ibrutinib, an irreversible inhibitor of BTK [333,334] which induces autophagy [335,336], is considered to have revolutionized CLL treatment, patients still present acquired drug resistance and low complete remission rates [337,338]. Various studies have demonstrated the hypersensitivity of CLL cells to LDs in comparison to healthy B-cells [339-341]. Hence, the combination of ibrutinib with lysosome-sensitizing agents has been explored [342,343]. This included the repurposing of widely used cationic amphiphilic antihistamines (CAAs) which have recently been recognized as LDs [60,63,69,343-347]. These CAAs, including for example desloratadine, clemastine, and ebastine, bear a specific chemical structure containing hydrophobic rings and a hydrophilic amine group. This structure allows them on the one hand to traverse cell membranes and on the other hand undergo accumulation in acidic lysosomes upon amine group protonation.

Sonodynamic therapy

RDT using X ray has an advantage of deep tissue penetration, enabling tumor targeting throughout the body [348]. However, irradiation has inevitable side effects including secondary tumors induced by this mutagenic treatment [349], radiation-induced vasculopathy [350], cardiovascular disorders [351], and serious fatigue [352], all of which limit the biomedical application of RDT. PDT, which combines light energy with a wavelength compatible photosensitizer, is considered a well-established method for cancer treatment, including via lysosomal damage [71-76]. However, PDT has many limitations and disadvantages [353,354]; primarily, near-infrared-based PDT laser has poor tissue penetration (~1-5 mm) [355,356], requires photosensitizers at specific wavelengths and induces serious photosensitivity of healthy tissues like the skin [357].

In comparison to RDT and PDT, US-based sonodynamic therapy (SDT) has high tissue penetration capacity (> 10 cm) [358] and displays negligible side effects [359]. SDT is useful for drug delivery [360,361], including for the temporary opening of the BBB [362] to facilitate delivery of drugs for the treatment of various CNS malignancies [363] including GBM [364] and brain metastases [365]. SDT is also used with various sonosensitizers to generate cytotoxic ROS for cancer therapeutics [359,365,366], including immunotherapy [367-371], eliciting the desirable abscopal effect [366]. However, as observed with other anti-cancer treatment modalities, SDT can induce autophagy which mitigates the anti-cancer therapeutic effects [372-375]. Thus, combining SDT with lysosome-targeted autophagy inhibitors restores tumor sensitivity to treatment [376-379], and induces LMP-driven ICD, stimulating an adaptive immune response [114].

Achieving both inhibition of autophagy and LMP using SDT was demonstrated by Yong Liu et al. [379]. This group implemented an innovative NP strategy by using a piezoelectric material, which can convert mechanical pressure into electrical energy [380,381], to generate Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3 (BCZT) NPs [379]. Following endocytosis, these BCZT NPs localized within lysosomes of murine B16 melanoma cells, where they had only minor deleterious effects on lysosomal function. However, during a 6 min application of 1.5 W/cm2 US, the US-mediated mechanical forces [382] caused the charge centers within the BCZT NPs to shift, resulting in a dipole moment [383] and consequent formation of (e-) electrons on their surface [379]. These electrons interacted with the abundant protons (H+) in the lysosomes to produce hydrogen gas (H2), thereby drastically alkalinizing the lysosomes. This resulted in a 75% reduction in lysosomal acid phosphatase activity and robust LMP, leading to autophagy inhibition and rapid cell death. The combination of BCZT NPs + US was also tested in vivo on B16 tumor-bearing mice, where these NPs consistently accumulated in the tumor's lysosomes. The combined therapy with BCZT NPs + US displayed an efficacious 86.1% tumor suppression rate (p < 0.0001), while the BCZT NPs alone elicited a non-significant 10% reduction in tumor volume. This allows for US-directed targeted therapy, even if the NPs themselves are not tumor specific [379].

An additional piezo-sonosensitizer was designed by Xianbo Wu et al., who synthesized a novel O2 self-sufficient Ir-C3N5 nanocomplex, composed of a nitrogen-rich carbon nitride (C3N5) nanosheet and 30% iridium(III) [384]. Ir-C3N5 exhibited a strong dipole moment and consequent high piezoelectric catalytic performance under US. The surface electrons reacted with O2 to generate singlet oxygen (1O2), and the intermediate ·O2- reacted with additional electrons to form H2O2, followed by H2O2 decomposition to generate ·OH, thus producing high ROS levels. Moreover, as a self-sufficient O2 producer, Ir-C3N5 can be used under hypoxic conditions, which exist in both solid and hematological malignancies [385]. When incubated with human A-375 melanoma cells, Ir-C3N5 was shown to accumulate in lysosomes, though no explanation was given to this specific organelle targeting [384]. However, since the accumulation in lysosomes was not time dependent, this probably did not occur via endocytosis, and the asymmetric structure of the C3N5 component with positive and negative charge centers, probably conferred lysosomotropic characteristics. Upon US activation (0.5W, 1 MHz, 3 min), lysosomal Ir-C3N5 generated high levels of ROS leading to LMP. The latter induced robust autophagy inhibition and cell death, ~70% apoptosis and necrosis for Ir-C3N5 + US vs ~10% for Ir-C3N5 and only ~3% in the control group. To verify that Ir-C3N5 + US induced ICD, the authors conducted an in vitro transwell macrophage polarization assay. As controls for M1 and M2 polarization, mouse J774A.1 macrophages were incubated with the canonical stimuli LPS and IL-4 for M1 and M2, respectively. Apoptotic A-375 cells following treatment with Ir-C3N5 + US, stimulated M1 polarization as strong as LPS, including the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-6. Using subcutaneous murine B16-F10 tumor models, Ir-C3N5 + US was shown to stimulate CTLs infiltration into the tumor and lymph nodes. This stimulation resulted in the complete inhibition of both the primary tumor and distant tumor growth as well as eliminated lung metastases, suggesting an efficient abscopal effect. The combined treatment with Ir-C3N5 + US increased the survival rate of the mice beyond the scope of the experiment (> 50 days) [384].

Future perspectives

The current review highlights the burning necessity of simultaneously targeting tumor cells as well as the TME and tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) [386]. Targeting only tumor cells often results in chemoresistance, as the TME and TIME actively promote tumor cell survival, growth, invasion, immune evasion and metastasis [387-391]. Lysosomal modulating agents that impair autophagy simultaneously target the tumor and its TME and TIME, while minimizing adverse effects. Targeting lysosomes of TAMs and stroma cells can convert an immunosuppressive microenvironment into an immune-supportive one, enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapies. Several clinical trials using CQ/HCQ in combination therapy, have shown great promise (Table S1) [53] and warrant further dedicated studies. This is particularly relevant in high mortality cancer types with no efficacious therapy like PDAC. As abovementioned, PDAC is characterized by a highly dense desmoplasia. The latter is present in other types of tumors, e.g., cervical cancer [392], breast cancer [393], lung cancer [394], squamous cell carcinoma [395] and small intestine neuroendocrine tumors [396], leading to chemoresistance and dismal prognosis [392,395,397-399]. Thus, it is paramount to overcome this desmoplastic barrier for efficient cancer eradication. In this regard, recent studies reveal that desmoplasia is promoted by autophagy [257-259]. Hence, we find autophagy inhibition via lysosomal targeting a promising therapeutic strategy. Figure 4 illustrates the role of autophagy in shaping the TME and TIME of PDAC, and the reversal effect of autophagy inhibition by lysosome targeting agents. The anti-fibrotic activity of HCQ inhibits ECM synthesis by reducing the secretion of collagen and hyaluronan by stromal fibroblasts [258,276]. The polarization of macrophages to the M1 phenotype reduces the levels of TGF-β which promotes autophagy and ECM stiffness [400]. Reduction in desmoplasia along with immune stimulation restores chemotherapeutic drug accessibility to the tumor and chemosensitivity, as well as an enhanced anti-tumor immune response. It should be noted that HCQ is used in this demonstration since it was shown to reduce desmoplasia in murine models [258,276]. However, since an HCQ dose of 1,200 mg/day is required to induce inhibition of autophagy in cancer patients [275,401], a dose that can elicit grade 3-4 adverse effects [401-403], other more potent lysosome disrupting agents should be tested, or HCQ should be encapsulated. A potential candidate as an HCQ substitute is the FDA approved TKI nintedanib [404]. From a mechanistic perspective, nintedanib blocks multiple tyrosine kinase receptors including VEGFR, PDGFR, and FGFR, which are paramount in the signaling pathways which culminate in pathological lung fibrosis. Nintedanib accumulates in the membrane of lysosomes and disrupts their integrity and function [59,405,406], leading to autophagy inhibition and autophagic cell death [405,407]. Consistently, nintedanib has displayed potent antifibrotic activities that reprogram the TME by reducing ECM secretion by CAFs as well as enhancing immunity and reducing TGF-β levels [408-410]. While these abilities are exploited for the treatment of lung fibrosis [411,412], nintedanib is still primarily referred to as a TKI and not as a bona fide lysosomotropic agent. Based on the established anti-fibrotic activity of nintedanib, clinical trials are warranted that will explore its plausible antitumor activity as a desmoplasia inhibitor, as monotherapy or in combination with other chemotherapeutics, in desmoplastic cancers like PDAC. In this respect, a clinical trial has been already conducted in PDAC (NCT02902484).

In a recent review, Stephanie Nagy et al., retrospectively analyzed the impact of CAAs on the efficiency of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)-based immunotherapy in cancer patients [413]. The six studies included in this analysis, encompassing 4,171 patients with different types of malignancies, showed great potential. Collectively, patients who received a combination of CAAs and ICIs displayed a significant improvement in overall survival rates and longer progression-free survival rates compared to patients who did not receive antihistamines [413]. Considering the minimal adverse effects of second generation CAAs [414], and their ability to induce lysosomal alkalinization and LMP [69,343,345,347], further clinical evaluation should be performed. The same can be conveyed about ginsenosides which exhibit multiple beneficial properties, including health improvement, anti-tumor activity and enhanced immunity. Thus, drug repurposing to generate efficacious combination therapies targeting the tumor as well as the stroma should be in the epicenter of future innovative therapeutic drug development efforts (Figure 5).

Abbreviations

5-FU: 5-Fluorouracil; APCs: antigen presenting cells; aRCT: adjuvant-radiochemotherapy; ATG5: autophagy protein 5; Au@Cu2-xSe: core-shell copper selenide-coated gold NPs; BafA1: bafilomycin A1; BBB: blood-brain-barrier; BCR: B-cell receptor; BCZT: Ba0.85Ca0.15Zr0.1Ti0.9O3; BEV: bevacizumab; bLDH: MgAl-based hydrotalcite; BMDMs: bone marrow derived macrophages; BTK: Bruton's tyrosine kinase; CAFs: cancer associated fibroblasts; CAAs: cationic amphiphilic antihistamines; CCOC: clear cell ovarian carcinoma; CHEK1: checkpoint kinase 1; CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CML: chronic myeloid leukemia; CpG: cytidine monophosphate guanosine oligodeoxynucleotide; CPP: cell-penetrating peptide; CQ: chloroquine; CRC: colorectal cancer; CTLs: cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, CD8+ T cells; CTSB: cathepsin B; DDR: DNA damage repair; DHA: dihydroartemisinin; ECM: extracellular matrix; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; ESR2: estrogen receptor 2; GBM: glioblastoma multiforme; GICs: glioma initiating cells; GLUT1: glucose transporter 1; H&E: hematoxylin and eosin; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; HCQ-Lip: HCQ-loaded liposomes; ICD: immunogenic cell death; ICIs: immune checkpoint inhibitors; IFN-γ: interferon gamma; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; IQ: imidazoquinoline; Ir-C3N5: nitrogen-rich carbon nitride nanosheet and iridium(III); LCD: lysosomal cell death; LDs: lysosomotropic drugs; LMP: lysosomal membrane permeabilization; LNPs: lipid NPs; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; LSCs: leukemic stem cells; LTA: lipoteichoic acid; Mcoln1: mucolipin; MDSCs: myeloid-derived suppressor cells; MRD: minimal residual disease; MSNs: mesoporous silica NPs; NCF1: neutrophil cytosolic factor 1; NK: natural killer; NP: nanoparticle; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; PDA: polydopamine; PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor; PDT: photodynamic therapy; PFS: progression free survival; PGN: pH-gated nanoadjuvant; PGNs: pH-gated nanoparticles; PTX: paclitaxel; RDT: radiation therapy, radiotherapy; Rg3-LPs: ginsenoside Rg3 liposomes; rGBM: recurrent GBM; RGD: arginyl-glycyl-aspartic acid tripeptide; Rh2-lipo: ginsenosides Rh2 liposome; RLNP/DC: LNPs co-loaded with CQ and DHA, and decorated with RGD; SDT: sonodynamic therapy; TAMs: tumor associated macrophages; T-B: TAT-Beclin 1 peptide; TDLN: tumor-draining lymph nodes; TFP: trifluoperazine; TGF-β: transforming growth factor β; TIME: tumor immune microenvironment; TKIs: tyrosine kinase inhibitors; TLR: toll like receptor; TME: tumor microenvironment; TMZ: temozolomide; TNBC: triple negative breast cancer; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor α; TR: a targeting cyclic RGD tripeptide with a pH-responsive CPP; Tregs: regulatory T cells; TR-PTX/HCQ-Lip: liposome-based NPs decorated with TR, loaded with HCQ and PTX; UIO: ultrasmall iron oxide; UIOQM-IQ: UIO NP conjugated to a CTSB-cleavable peptide, an aggregation-induced emission fluorophore, and surface IQ; US: ultrasound; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

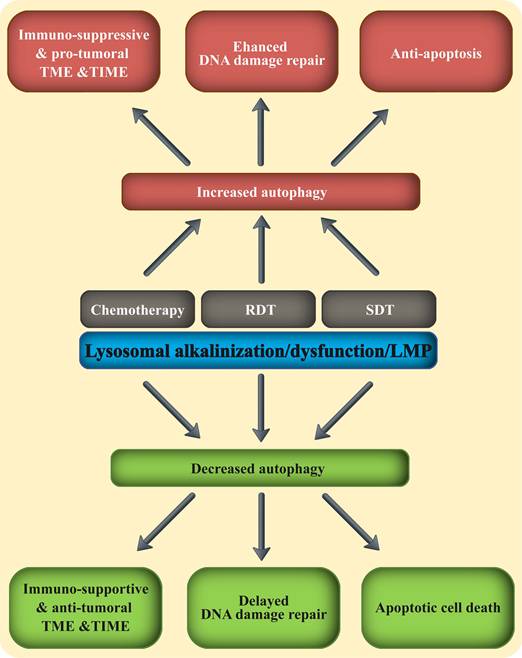

Combining lysosomal disrupting agents with the three fundamental anti-cancer treatment modalities. The three main anti-cancer therapeutic modalities including chemotherapy, RDT and SDT, were all shown to increase autophagy in malignant and immune cells. This enhanced autophagy mitigates their therapeutic activity, by promoting an immune-suppressive TME & TIME and immune evasion, upregulated DNA damage response and repair, as well as anti-apoptosis. Adding a lysosomal disrupting agent to any of these three therapeutic modalities, blocks autophagy and reverses the pro-tumoral TME & TIME to anti-tumor environment.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary table.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Edmond Sabo, director of the surgical pathology unit at Carmel Medical Center, Haifa, Israel, for providing us with H&E-stained pancreas biopsy slides, generated during initial diagnosis of a PDAC patient. A written consent was obtained from the patient.

ChatGPT 5 academic was used to generate individual images within Figures 1, 2 and 4.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Ohkuma S, Poole B. Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH by various agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75(7):3327-31

2. Johnson DE, Ostrowski P, Jaumouillé V, Grinstein S. The position of lysosomes within the cell determines their luminal pH. J Cell Biol. 2016;212(6):677-92

3. Webb BA, Aloisio FM, Charafeddine RA, Cook J, Wittmann T, Barber DL. pHLARE: A new biosensor reveals decreased lysosome pH in cancer cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2021;32(2):131-42

4. Hu Y, Wang X, Lu K, Cheang C, Liu Y, Zhu Y. et al. Aggregation-induced emission of DNA fluorescence as a novel pan-marker of cell death, senescence and sepsis in vitro and in vivo. Theranostics. 2026;16(2):1063-81

5. Schröder BA, Wrocklage C, Hasilik A, Saftig P. The proteome of lysosomes. Proteomics. 2010;10(22):4053-76

6. Ratto E, Chowdhury SR, Siefert NS, Schneider M, Wittmann M, Helm D. et al. Direct control of lysosomal catabolic activity by mTORC1 through regulation of V-ATPase assembly. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4848

7. Yoon MC, Hook V, O'Donoghue AJ. Cathepsin B Dipeptidyl Carboxypeptidase and Endopeptidase Activities Demonstrated across a Broad pH Range. Biochemistry. 2022;61(17):1904-14

8. Abe A, Shayman JA. Purification and characterization of 1-O-acylceramide synthase, a novel phospholipase A2 with transacylase activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(14):8467-74

9. Patra S, Patil S, Klionsky DJ, Bhutia SK. Lysosome signaling in cell survival and programmed cell death for cellular homeostasis. J Cell Physiol. 2023;238(2):287-305

10. Ballabio A, Bonifacino JS. Lysosomes as dynamic regulators of cell and organismal homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(2):101-18

11. Settembre C, Perera RM. Lysosomes as coordinators of cellular catabolism, metabolic signalling and organ physiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(3):223-45

12. Zhang Z, Yue P, Lu T, Wang Y, Wei Y, Wei X. Role of lysosomes in physiological activities, diseases, and therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2021 14(1)

13. Inpanathan S, Botelho RJ. The Lysosome Signaling Platform: Adapting With the Times. Front cell Dev Biol. 2019;7(JUN):113

14. Lawrence RE, Zoncu R. The lysosome as a cellular centre for signalling, metabolism and quality control. Vol. 21, Nature Cell Biology. Nature Publishing Group. 2019 p. 133-42

15. Eriksson I, Öllinger K. Lysosomes in Cancer—At the Crossroad of Good and Evil. Cells. 2024 13(5)

16. Davidson SM, Vander Heiden MG. Critical Functions of the Lysosome in Cancer Biology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;57(1):481-507

17. Mahapatra KK, Mishra SR, Behera BP, Patil S, Gewirtz DA, Bhutia SK. The lysosome as an imperative regulator of autophagy and cell death. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(23):7435-49

18. Nanayakkara R, Gurung R, Rodgers SJ, Eramo MJ, Ramm G, Mitchell CA. et al. Autophagic lysosome reformation in health and disease. Autophagy. 2023;19(5):1378-95

19. Kuchitsu Y, Taguchi T. Lysosomal microautophagy: an emerging dimension in mammalian autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2024;34(7):606-16

20. Trelford CB, Di Guglielmo GM. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian autophagy. Biochem J. 2021;478(18):3395-421

21. Vargas JNS, Hamasaki M, Kawabata T, Youle RJ, Yoshimori T. The mechanisms and roles of selective autophagy in mammals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24(3):167-85

22. Chen T, Tu S, Ding L, Jin M, Chen H, Zhou H. The role of autophagy in viral infections. J Biomed Sci. 2023 30(1)

23. Yan X, Zhou R, Ma Z. Autophagy—Cell Survival and Death. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1206:667-96

24. Bata N, Cosford NDP. Cell Survival and Cell Death at the Intersection of Autophagy and Apoptosis: Implications for Current and Future Cancer Therapeutics. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4(6):1728-46

25. Das S, Shukla N, Singh SS, Kushwaha S, Shrivastava R. Mechanism of interaction between autophagy and apoptosis in cancer. Apoptosis. 2021;26(9-10):512-33

26. Yu G, Klionsky DJ. Life and Death Decisions—The Many Faces of Autophagy in Cell Survival and Cell Death. Biomolecules. 2022 12(7)

27. Liu SZ, Yao SJ, Yang H, Liu SJ, Wang YJ. Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2023 14(10)

28. He C. Balancing nutrient and energy demand and supply via autophagy. Curr Biol. 2022;32(12):R684-96

29. Feng Y, Chen Y, Wu X, Chen J, Zhou Q, Liu B. et al. Interplay of energy metabolism and autophagy. Autophagy. 2024;20(1):4-14

30. Lemasters JJ. Variants of mitochondrial autophagy: Types 1 and 2 mitophagy and micromitophagy (Type 3). Redox Biol. 2014;2(1):749

31. Fu X, Cui J, Meng X, Jiang P, Zheng Q, Zhao W. et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, cell death and tumor: Association between endoplasmic reticulum stress and the apoptosis pathway in tumors (Review). Oncol Rep. 2021;45(3):801-8

32. Merighi A, Lossi L. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling and Neuronal Cell Death. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 23(23)

33. Chipurupalli S, Samavedam U, Robinson N. Crosstalk Between ER Stress, Autophagy and Inflammation. Front Med. 2021 8

34. Qin Y, Ashrafizadeh M, Mongiardini V, Grimaldi B, Crea F, Rietdorf K. et al. Autophagy and cancer drug resistance in dialogue: Pre-clinical and clinical evidence. Cancer Lett. 2023 570

35. Niu X, You Q, Hou K, Tian Y, Wei P, Zhu Y. et al. Autophagy in cancer development, immune evasion, and drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2025 78

36. Hu X, Wen L, Li X, Zhu C. Relationship Between Autophagy and Drug Resistance in Tumors. Mini-Reviews Med Chem. 2022;23(10):1072-8

37. Qiang L, Zhao B, Shah P, Sample A, Yang S, He YY. Autophagy positively regulates DNA damage recognition by nucleotide excision repair. Autophagy. 2016;12(2):357-68

38. Eliopoulos AG, Havaki S, Gorgoulis VG. DNA Damage Response and Autophagy: A Meaningful Partnership. Front Genet. 2016 7(NOV)

39. Ambrosio S, Majello B. Autophagy Roles in Genome Maintenance. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(7):1-24

40. Park C, Suh Y, Cuervo AM. Regulated degradation of Chk1 by chaperone-mediated autophagy in response to DNA damage. Nat Commun. 2015 6

41. Elliott IA, Dann AM, Xu S, Kim SS, Abt ER, Kim W. et al. Lysosome inhibition sensitizes pancreatic cancer to replication stress by aspartate depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(14):6842-7

42. Zheng K, Li Y, Wang S, Wang X, Liao C, Hu X. et al. Inhibition of autophagosome-lysosome fusion by ginsenoside Ro via the ESR2-NCF1-ROS pathway sensitizes esophageal cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil-induced cell death via the CHEK1-mediated DNA damage checkpoint. Autophagy. 2016;12(9):1593-613

43. Saleh T, As Sobeai HM, Alhoshani A, Alhazzani K, Almutairi MM, Alotaibi M. Effect of Autophagy Inhibitors on Radiosensitivity in DNA Repair-Proficient and -Deficient Glioma Cells. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022 58(7)

44. Zhou W, Guo Y, Zhang X, Jiang Z. Lys05 induces lysosomal membrane permeabilization and increases radiosensitivity in glioblastoma. J Cell Biochem. 2020;121(2):2027-37

45. Debnath J, Gammoh N, Ryan KM. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24(8):560-75

46. Vitto VAM, Bianchin S, Zolondick AA, Pellielo G, Rimessi A, Chianese D. et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Autophagy in Cancer Development, Progression, and Therapy. Biomedicines. 2022 10(7)

47. Turek K, Jarocki M, Kulbacka J, Saczko J. Dualistic role of autophagy in cancer progression. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2021 30(12)

48. Bhol CS, Senapati PK, Kar RK, Chew G, Mahapatra KK, Lee EHC. et al. Autophagy paradox: Genetic and epigenetic control of autophagy in cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2025 630

49. Chen JL, Wu X, Yin D, Jia XH, Chen X, Gu ZY. et al. Autophagy inhibitors for cancer therapy: Small molecules and nanomedicines. Pharmacol Ther. 2023 249

50. Jain V, Singh MP, Amaravadi RK. Recent advances in targeting autophagy in cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2023;44(5):290-302

51. Hama Y, Ogasawara Y, Noda NN. Autophagy and cancer: Basic mechanisms and inhibitor development. Cancer Sci. 2023;114(7):2699-708

52. Tonkin-Reeves A, Giuliani CM, Price JT. Inhibition of autophagy; an opportunity for the treatment of cancer resistance. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023 11

53. Mohsen S, Sobash PT, Algwaiz GF, Nasef N, Al-Zeidaneen SA, Karim NA. Autophagy Agents in Clinical Trials for Cancer Therapy: A Brief Review. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(3):1695-708

54. Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K. et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8(4):445-544

55. Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy. 2007;3(5):452-60

56. Pisonero-Vaquero S, Medina DL. Lysosomotropic Drugs: Pharmacological Tools to Study Lysosomal Function. Curr Drug Metab. 2017;18(12):1147-58