10

Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(6):2842-2868. doi:10.7150/ijbs.126580 This issue Cite

Review

Role of Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Cardiovascular Disease: Molecular Insights and Metabolic Perspectives

1. Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, No. 37 GuoXue Xiang, Chengdu, Sichuan 610041, China.

2. Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Chengdu Shang Jin Nan Fu Hospital, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan 610041, China.

3. Institute of Human Genetics, Jena University Hospital, Jena 07747, Germany.

4. Department of Medical Oncology, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, No. 37 GuoXue Xiang, Chengdu, Sichuan 610041, China.

5. Lung Cancer Center/Lung Cancer Institute, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, No. 37 GuoXue Xiang, Chengdu, Sichuan 610041, China.

#These authors contributed equally: Xianzhe Yu, Dou Yuan.

Received 2025-10-11; Accepted 2026-2-5; Published 2026-2-18

Abstract

Copper is an essential trace element; however, its homeostasis is frequently disrupted in cardiovascular diseases, which are a leading cause of mortality worldwide. The recent discovery of cuproptosis—a copper-dependent form of regulated cell death (RCD)—has provided a crucial mechanistic link between this imbalance and cardiomyocyte loss. In this review, we synthesize the current understanding of how dysregulated copper metabolism and cuproptosis drive the pathogenesis of major cardiovascular conditions, including myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, atherosclerosis, diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), and sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction, through pathways such as mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation. We further evaluated emerging therapeutic strategies that target copper homeostasis—including chelators, chaperone inhibitors, and ionophores—and critically analyzed the translational challenges they face, such as off-target effects and preclinical model limitations. Advancing our knowledge of cardiac copper biology holds significant promise for the development of novel and precise therapeutic approaches for cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: copper, cuproptosis, copper homeostasis, cardiovascular disease, mitochondrial dysfunction

Introduction

Cell death is a critical driver of cardiovascular disease pathogenesis, contributing to tissue damage, dysfunction, and inflammation [1]. Among the various regulated cell death (RCD) pathways, a novel form—cuproptosis—has recently emerged, uniquely triggered by disruptions in copper metabolism [2]. Mechanistically distinct from other forms of cell death, cuproptosis is characterized by the direct binding of copper to lipoylated enzymes in the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, leading to proteotoxic stress and subsequent cell death, independent of classical apoptotic signaling [3].

Copper, an essential trace element, acts as a cofactor for numerous metabolic enzymes and is vital for physiological processes, including antioxidant defense, mitochondrial respiration, and energy metabolism [4]. Cellular function relies on a tightly regulated copper metabolic network that maintains copper concentrations within a narrow range. Copper deficiency impairs copper-dependent enzymes, whereas copper overload promotes excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, leading to oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA [5, 6]. This oxidative stress can activate classical apoptotic pathways, a process termed copper-induced apoptosis, which is mediated by DNA/membrane damage and the caspase/Bcl-2/p53 pathway and can be inhibited by caspase inhibitors [7]. In contrast, cuproptosis represents a separate copper-dependent pathway in which excess copper directly targets mitochondrial metabolism, inducing cell death through aggregated lipoylated proteins and iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster loss, independent of apoptotic signaling [3, 8]. Copper-induced oxidative stress, although a key modulator of cellular damage, is not a direct cell death pathway. It is a cellular stress state resulting from copper-driven ROS accumulation, which can facilitate apoptosis or other death modalities, such as ferroptosis, and can be alleviated by antioxidants [9, 10].

Given that cellular function depends critically on precise copper homeostasis, any disturbance in this balance can have severe pathological consequences [11]. As a novel RCD modality involving multiple signaling and metabolic pathways, cuproptosis has been implicated in various cardiovascular conditions, including cardiomyopathy, heart failure (HF), and myocardial injury [12]. Therefore, this review aims to summarize the regulation of copper homeostasis in cardiomyocytes, explore cuproptosis-related targets in cardiovascular diseases, and discuss the translational potential of therapies targeting this pathway.

Molecular and Metabolic Drivers of Cuproptosis

Cells undergoing cuproptosis exhibit unique biochemical, genetic, metabolic, and morphological features that distinguish them from other recognized forms of cell death, such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, necroptosis, and ferroptosis [13, 14] (Table 1). Apoptosis is a caspase-dependent process activated by intrinsic (e.g., mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization) or extrinsic (e.g., death receptor activation) stimuli. Key cardiac triggers include hypoxia, oxidative stress, and neurohormonal overload [15]. Its morphological hallmarks include cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and formation of apoptotic bodies [15]. Ferroptosis is driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, primarily initiated by glutathione (GSH) depletion or inactivation of GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4). It is a key contributor to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury [16]. Morphologically, it is associated with distinct mitochondrial changes, such as mitochondrial reticulum shrinkage and fragmentation [3]. Although cuproptosis can intersect with pathways such as apoptosis and ferroptosis, its initiation and execution are uniquely co-regulated by interconnected metabolic pathways involving copper, GSH, and lipids, which are particularly critical in cardiomyocytes [17]. Given these distinct mechanisms, cuproptosis has been implicated as a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of diverse cardiovascular diseases, including dilated cardiomyopathy, HF, and atherosclerosis [12].

Molecular intersections and distinctions between cuproptosis and other regulated cell-death pathways

| Cell death pathway | Primary trigger | Morphological features | Biochemical characteristics | Core execution mechanism | Key molecules/ hallmarks | Key genes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cuproptosis | Excess copper ions | Mitochondrial shrinkage and plasma membrane rupture | Cu2+ binds to lipoacylated DLAT and induces disulphide bond-dependent aggregation of lipoylated DLAT | Copper-binding to lipoylated TCA cycle proteins, leading to protein aggregation and proteotoxic stress. | Copper, FDX1, and lipoylated DLAT | FDX1 | [265] |

| Apoptosis | Death receptor signaling, DNA damage, and cellular stress | Apoptotic bodies' chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, and cell shrinkage | DNA fragmentation, and the dismantling of cellular components | Caspase activation, DNA fragmentation, and the dismantling of cellular components. | Caspases, BCL-2 family, and cytochrome c | BCL-2, Bak, and caspases | [266] |

| Ferroptosis | Iron-dependent generation of lipid peroxidation | Small mitochondria and elevated mitochondrial membrane density. | Decreased expression of GSH and GPX4, increased divalent iron and lipid peroxidation | Inactivation of GPX4, leading to lethal accumulation of lipid peroxides. | Iron, lipid peroxides, and GPX4 | GPX4 | [267] |

| Pyroptosis | Pathogen Shigella infection | Cell swelling, plasma membrane leakage, and chromatin condensation | Caspase-1 activation dependent, GSDMD cleavage and inflammatory factor release | Pore formation in the plasma membrane, causing inflammatory cell lysis. | Gasdermin D, inflammasome, and IL-1β | GSDMD, NLRP 3, and caspases-1/4/5 | [268] |

| Necroptosis | Tumor necrosis factor receptor signaling and caspase-8 inhibition | Disintegration of plasma membrane, swelling of organelles, and spillage of cellular contents | Activation of RIPK1, RIPK4, and MLKL and a decrease in ATP levels | RIPK1/RIPK3/MLKL-mediated plasma membrane rupture. | RIPK3 and phosphorylated MLKL | RIPK3 and MLKL | [269] |

Heart Copper Metabolism and Cuproptosis

Regulation of Copper Homeostasis in the Cardiovascular System

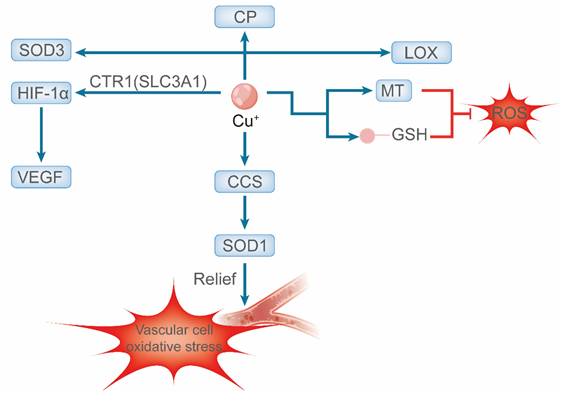

Copper homeostasis is a tightly regulated process that is essential for cardiovascular health and balances systemic absorption, distribution, utilization, and excretion. This equilibrium is particularly critical in high-energy-demand tissues, such as the heart, where copper serves as an indispensable cofactor for key metabolic enzymes and mitochondrial function [18, 19]. Intracellularly, copper buffering by molecules such as GSH and metallothionein (MT) prevents ROS generation via Fenton reactions [20]. Specific chaperones then deliver copper to target proteins; for instance, the copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase (CCS) activates Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), which is a key antioxidant enzyme in vascular cells [21]. Notably, CCS expression is regulated by copper levels, increasing during deficiency and degrading under excess conditions [22].

The cardiovascular roles of copper are multifaceted. As the catalytic core of cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV, CCO), it is fundamental to mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production [23]. It also activates other crucial enzymes, including extracellular SOD3, ferroxidase ceruloplasmin (CP) (vital for iron metabolism), and lysyl oxidase (LOX) [24]. LOX crosslinks collagen and elastin, providing structural integrity and elasticity to the heart and vasculature [25]. The critical dependence on copper is underscored by pathologies arising from its dysregulation. For example, copper restriction impairs CCO assembly and function, leading to reduced mitochondrial ATP production and oxygen consumption [26]. Beyond metabolism and structure, copper promotes angiogenesis by stabilizing hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) via transporters such as Copper Transporter 1 (CTR1; Solute Carrier Family 31 Member A1, SLC31A1) and ATPase Copper Transporting Alpha (ATP7A), thereby enhancing pro-angiogenic gene expression [27, 28].

Given these essential functions, serum copper levels are closely associated with cardiometabolic risk factors, including dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, and obesity, and are regarded as predictive indicators of cardiovascular disease risk [29]. In summary, disruptions in copper homeostasis—whether arising from deficiency, excess, or dysfunction of molecular chaperones and transporters—are fundamentally implicated in the pathogenesis of various cardiovascular diseases [30] (Figure 1).

Schematic representation of copper-mediated regulation of vascular redox homeostasis. Intracellularly, Cu⁺ acts as an essential cofactor that activates secretory enzymes (e.g., CP and LOX) is delivered to SOD1 via CCS to combat superoxide and stabilizes HIF-1α to promote VEGF expression. Cellular redox balance is maintained by copper buffers (MT) and antioxidants (GSH).

Copper Homeostasis Imbalance and Cardiovascular Disease

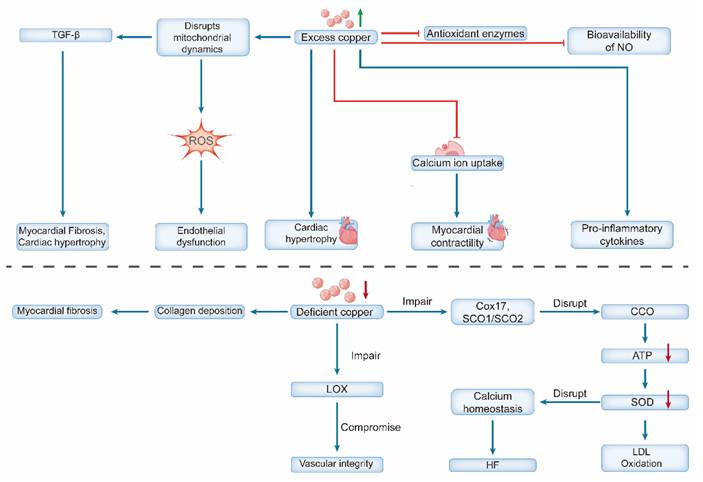

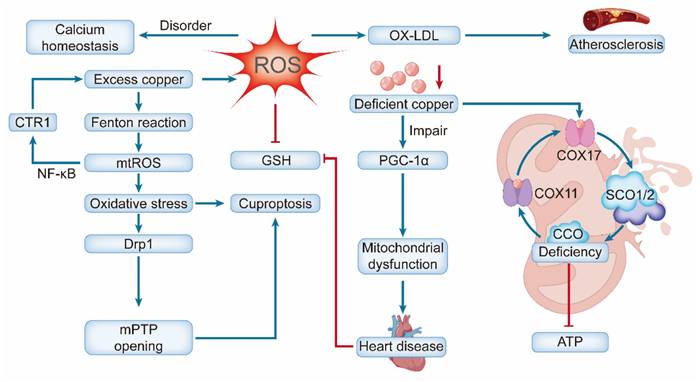

Copper overload induces cardiovascular injury through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Systemically, excess copper catalyzes Fenton-like reactions, generating excessive ROS that cause oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA [31]. It concurrently impairs antioxidant defenses (e.g., by inhibiting catalase) [32] and promotes inflammation by elevating pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and reducing nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability [33]. At the cellular level, these insults trigger distinct pathogenic pathways. In endothelial cells (ECs), copper overload disrupts mitochondrial dynamics, increases fission and ROS production, and ultimately leads to cell death [34] In cardiomyocytes, copper promotes hypertrophy and inflammation [35], disrupts fatty acid and lipid metabolism, upregulates autophagy-associated proteins and genes, and impedes calcium ion uptake by the sarcoplasmic reticulum, thereby inhibiting myocardial contractility [36]. Chronic copper overload is a potent driver of pathological cardiac remodeling, primarily by inducing sustained oxidative stress. The accumulation of copper catalyzes excessive ROS production, which directly damages mitochondrial integrity and function and activates pro-fibrotic signaling pathways—most notably transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) [37]. These structural and cellular alterations culminate in adverse outcomes. The resulting myocardial fibrosis disrupts the normal electrical conduction system of the heart, creating a substrate for electrophysiological instability. This, combined with the accompanying hypertrophic and neurohormonal changes, significantly increases the susceptibility to severe arrhythmias, including ventricular tachycardia and atrial fibrillation [38, 39]. Elevated serum copper levels, often observed in aging and diabetes, are both a driver and a biomarker of vascular damage, forming a vicious cycle that accelerates vascular aging and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease [40, 41]. Recent bioinformatic studies have further underscored its clinical relevance by highlighting a pronounced cuproptosis signature in myocardial infarction, involving key regulators such as SLC31A1 and ferredoxin-1 (FDX1) [42].

In contrast, copper deficiency promotes cardiovascular pathology through distinct mechanisms, primarily mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired structural integrity [43]. Deficiency disrupts the assembly and function of CCO by impairing copper-delivery proteins (e.g., COX17, SCO1/SCO2), severely reducing ATP production [44]. The resultant energy crisis and diminished SOD activity increase oxidative stress, promote low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation [45], and disrupt calcium homeostasis, leading to diastolic dysfunction and HF [46].

In the myocardium, a reduction in LOX activity disrupts the connective tissue architecture and impairs contractile function [47]. Conversely, elevated LOX activity promotes pathological cardiac remodeling by driving excessive collagen crosslinking and deposition. This leads to myocardial fibrosis, increased tissue stiffness, impaired angiogenesis, and ultimately contributes to HF [48, 49]. These defects ultimately lead to extensive structural and functional pathological alterations. The heart undergoes concentric hypertrophy, characterized by thickened ventricular walls without cavity enlargement, resembling pressure overload hypertrophy [50].

A critical aspect of copper deficiency is that its effects are often reversible. Copper supplementation in both animal models and humans (e.g., patients with SCO2 mutations) can restore CCO activity, reverse hypertrophy and fibrosis, and significantly improve cardiac function [51, 52]. This reversibility underscores the crucial and dynamic role of copper in maintaining cardiovascular health (Figure 2).

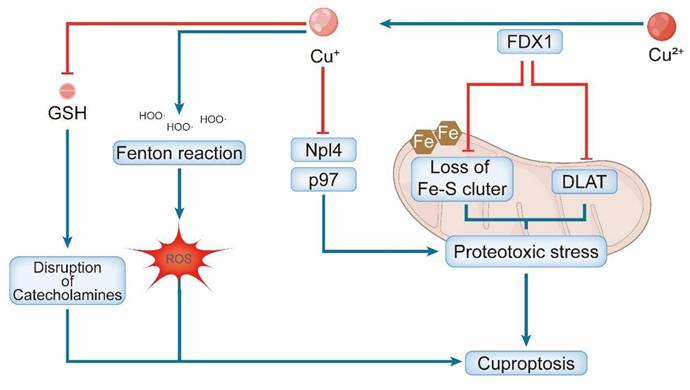

Copper Metabolism in Cuproptosis

Cuproptosis is a unique form of RCD driven by the cytotoxic accumulation of copper, with its upstream regulation and execution being critically dependent on the mitochondrial reductase FDX1 [53]. It reduces Cu²⁺ to the more reactive Cu⁺ and concurrently supplies electrons for the biosynthesis of the lipoyl moiety on key mitochondrial enzymes, such as Dihydrolipoamide Acetyltransferase (DLAT) [54]. This lipoylation creates high-affinity Cu + binding sites. Subsequent copper binding induces aberrant oligomerization of these proteins, disrupting the TCA cycle and initiating cell death [55].

The FDX1-mediated process culminates in profound proteotoxic stress driven by the aggregation of lipoylated mitochondrial proteins and the concomitant destabilization of Fe-S cluster proteins, which together lead to acute mitochondrial failure [3]. The copper ionophore elesclomol exhibits a paradoxical dual role that is critically dependent on the cellular context. In the presence of FDX1 and adequate copper, cuproptosis is induced by delivering extracellular Cu²⁺ into cells [56]. Conversely, under conditions of copper deficiency or FDX1 loss, elesclomol shifts to a protective function, restoring mitochondrial respiration by delivering copper to CCO [57]. This duality highlights the precise metabolic context required for cuproptosis. The physiological importance of copper import is further underscored by the essential role of the standard importer SLC31A1, as evidenced by reduced cardiac copper levels in SLC31A1-deficient mice [50, 58].

Furthermore, cuproptosis is amplified by secondary mechanisms. Copper ions can participate in Fenton-like reactions, generating ROS that cause oxidative damage to DNA and lipids [59]. Additionally, copper may inhibit the p97-Npl4 complex, which is essential for protein degradation, thereby exacerbating underlying proteotoxic stress [60]. GSH depletion and copper-catalyzed oxidation of catecholamines generate toxic quinones and ROS, which synergistically contribute to cuproptosis [3]. These parallel pathways collectively intensify the proteotoxic and oxidative burdens, ultimately leading to irreversible cell death (Figure 3).

Dual effects of copper dyshomeostasis on cardiovascular pathophysiology. Copper excess triggers oxidative stress (by impairing antioxidant enzymes and NO bioavailability) and disrupts Ca²⁺ homeostasis, leading to endothelial dysfunction, cardiac hypertrophy, and contractile impairment. Copper deficiency compromises cuproenzyme function, causing mitochondrial dysfunction (via impaired CCO), reduced antioxidant defense (via SOD downregulation), and structural defects (via reduced LOX activity leading to fibrosis). Collectively, these changes promote heart failure.

Crosstalk between Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis

Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of RCD driven by GSH depletion and GPX4 inactivation, is potently accelerated by copper through multi-pronged mechanisms that converge on iron-dependent lipid peroxidation [61, 62]. Copper promotes ferroptosis primarily by dismantling the core GPX4-centered antioxidant defense system. It depletes the intracellular pool of GSH, which is GPX4's essential cofactor, through the formation of Cu-GSH complexes and catalyzing its oxidation to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) [63, 64]. More critically, copper can directly bind to the cysteine residues of GPX4, triggering its autophagic degradation and consequent loss of activity, which impairs the cell's ability to repair lipid peroxidation [65].

Fe²⁺ acts as a key catalyst driving lipid peroxidation. The Fenton reaction generates highly reactive hydroxyl radicals. These radicals directly target polyunsaturated fatty acids within cell membranes, thereby initiating and propagating the chain reaction of lipid peroxidation [66]. This pro-ferroptotic effect is significantly amplified by the intricate crosstalk between copper and iron metabolism. Copper modulates post-translational regulation of iron homeostasis, potentially by inhibiting Fe-S cluster biosynthesis, and transcriptionally upregulates key iron uptake genes, such as transferrin receptor 1. These actions collectively lead to an expansion of the intracellular labile iron pool, thereby supplying more catalysts for Fenton reactions and intensifying lipid peroxidation [67, 68]. In cardiovascular diseases, the ferroptosis and cuproptosis pathways exhibit significant crosstalk. Copper stress promotes iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, whereas ferroptosis-derived mtROS enhance cuproptosis by accelerating DLAT oligomerization [69]. This interplay creates a vicious cycle of cardiomyocyte and vascular cell death, exacerbating cellular injury and pathological remodeling.

The clinical significance of the copper-ferroptosis axis is underscored by bioinformatic analyses revealing the co-dysregulation of ferroptosis and cuproptosis signatures in human diseases [70]. The shared dysregulation of key genes (e.g., POR, SLC7A5, and STAT3) in conditions such as sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy highlights the interplay between these metal-dependent death pathways [71]. Furthermore, the copper transporter ATP7A has been identified as a novel ferroptosis regulator, as its deficiency downregulates the cystine transporter SLC7A11, impairing GSH synthesis and sensitizing cells to ferroptosis [72]. Collectively, these findings illustrate an intricate network in which copper ions modulate cell fate by targeting multiple nodes of the ferroptotic pathway, presenting a promising avenue for therapeutic interventions.

Schematic representation of copper-induced cuproptosis. Excess copper is reduced by FDX1 to generate Cu⁺, which drives cell death via two primary mechanisms: (1) Cu⁺-mediated aggregation of lipoylated TCA cycle proteins (e.g., DLAT) and loss of Fe-S clusters, and (2) Cu⁺-induced disruption of the Npl4/p97 protein quality-control system. Both pathways converge to induce fatal proteotoxic stress in the mitochondria. Elevated Cu⁺ levels also deplete glutathione (GSH) and promote ROS generation, further contributing to cellular toxicity.

Chemotherapy-induced Cardiac Insult: Copper Homeostasis Disruption

Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity encompasses a range of cardiovascular complications, including cardiomyopathy, HF, and arrhythmias. Among the key causative agents, anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin (DOX), are particularly notable, as the severe cardiac damage they induce—characterized by ventricular dilatation, interstitial fibrosis, and progression to HF—significantly limits their clinical utility [73]. DOX-induced cardiotoxicity is driven by established mechanisms, such as oxidative stress, and centrally by dysregulated copper homeostasis and cuproptosis. Disruption of this critical ion balance impairs essential cardiac functions, including the maintenance of myocardial structure, electrical conduction, and contractile performance [74, 75].

This detrimental cascade begins with pathological intracellular copper accumulation. Mechanistically, DOX stabilizes the copper importer SLC31A1 (CTR1) by inhibiting its proteasomal degradation and downregulating the copper efflux transporter ATPase Copper Transporting Beta (ATP7B), leading to a net increase in cellular copper [17, 76]. The cuproptosis pathway is triggered in this copper-rich environment. DOX upregulates the expression and activity of FDX1, a reductase that converts accumulated Cu²⁺ to the more reactive Cu⁺ [77]. Furthermore, DOX upregulates the expression of key mitochondrial enzymes, including DLAT [78]. The increased abundance of lipoylated proteins, combined with the elevated labile copper pool induced by DOX, creates a permissive environment that drives cuproptosis. Cu⁺ ions directly bind to the lipoyl groups, inducing aberrant oligomerization of DLAT and other TCA cycle enzymes, promoting the loss of Fe-S cluster proteins. This cascade results in irreversible proteotoxic stress, ultimately leading to cardiomyocyte death [74]. The pivotal role of FDX1 in this pathway is underscored by experimental evidence that genetic ablation of FDX1 confers significant protection against DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in mice, preserving the left ventricular ejection fraction [76]. The intrinsic oxidative damage mediated by DOX is further amplified by Cu⁺-catalyzed Fenton-like reactions. This compounded oxidative insult exacerbates mitochondrial membrane damage, respiratory chain dysfunction and DNA damage [79, 80].

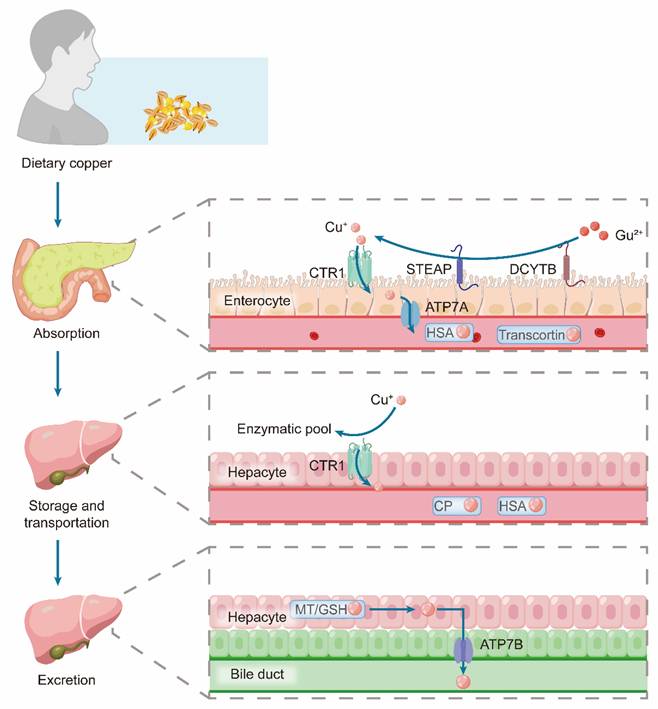

Physiological Copper Metabolism

Copper homeostasis is maintained through a tightly coordinated process involving systemic absorption, distribution, and excretion. Dietary copper absorption occurs primarily in the stomach, duodenum, and small intestine [81]. In this process, Cu²⁺ is first reduced to Cu⁺ by metalloreductases, such as duodenal cytochrome B (DCYTB) and six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate (STEAP). The resulting Cu⁺ is then transported to the apical membrane of intestinal cells via copper importers, including CTR1/SLC31A1, CTR2, and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) [82]. Subsequently, the copper-transporting ATPase ATP7A facilitates copper efflux from these cells into the portal circulation, a process that is upregulated during copper deficiency to enhance absorption [83]. ATP7A, which mediates dietary copper absorption in the intestine, and ATP7B, which promotes hepatic copper excretion, exert complementary functions that are critical for maintaining systemic copper homeostasis [84].

The liver is the central hub for systemic copper regulation. Dietary copper, which is bound to albumin, enters hepatocytes via the portal vein [85]. Within the liver, the closely related ATPase ATP7B performs two critical location-dependent functions: under normal conditions, it loads copper onto CP in the Golgi apparatus for secretion into the bloodstream, and during copper excess, it traffics to the biliary canaliculus to expel excess copper into the bile [86, 87]. This biliary pathway is the primary and irreversible route of copper elimination [88]. The entire system is dynamic; high copper intake downregulates intestinal absorption and upregulates biliary excretion, whereas deficiency states promote intestinal uptake and reduce biliary loss to conserve copper [89].

At the cellular level, a sophisticated chaperone network minimizes cytotoxic free copper levels. Upon entry via CTR1, copper is buffered by GSH or MTs [90]. The cytoplasmic chaperone Antioxidant 1 (ATOX1) then distributes copper to the ATP7A and ATP7B transporters in the trans-Golgi network for incorporation into cuproenzymes [91]. Under copper overload, these transporters relocate to vesicles or the plasma membrane to mediate the efflux [92]. Beyond its cytoplasmic role, ATOX1 can translocate to the nucleus and function as a copper-dependent transcription factor, potentially regulating pathways such as HIF-1α signaling [93] (Figure 4).

Additional chaperones target copper to specific organelles. CCS delivers copper to SOD1 in the cytoplasm and intermembrane space, whereas COX17 relays it to the mitochondria [83]. Within the mitochondria, copper is passed through secondary chaperones (SCO1, SCO2, and COX11) for incorporation into CCO, which is essential for respiratory function [94]. Proteins such as MEMO1 further fine-tune this network by suppressing ATOX1-mediated ROS under excess copper [95]. This precise regulation is critical for cardiovascular function. In the vasculature, it stabilizes endothelial NO synthase to preserve NO bioavailability and vasodilatory function [96].

Copper Homeostasis Dysregulation and Myocardial Pathological Reprogramming

The progression of cardiovascular diseases, such as myocardial infarction and HF, is driven by core pathological processes, including structural remodeling (e.g., hypertrophy and fibrosis) and metabolic reprogramming of cardiomyocytes toward a fetal-like state [97]. A growing body of evidence has identified disrupted copper homeostasis and subsequent activation of cuproptosis as key upstream drivers of this maladaptive process [98]. Pathological stressors, such as pressure overload or myocardial infarction, create an inflammatory microenvironment that elevates local copper concentrations, partly due to its release from necrotic cells and upregulated import in immune cells [99]. Excess copper exerts a dual pathological effect. First, it directly induces cardiomyocyte loss through cuproptosis, characterized by mitochondrial lipoylated protein aggregation and respiratory chain collapse [100]. Second, profound metabolic and oxidative stress from cuproptosis acts as a potent trigger for pathological myocardial reprogramming. It forces a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis and activates established pro-reprogramming signaling pathways, such as YAP/TAZ, which exacerbate inflammatory responses and fibrosis, thereby accelerating adverse ventricular remodeling [49, 101]. In vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), it disrupts the TCA cycle and provokes ROS production, leading to cellular hypertrophy and phenotypic switching, which culminates in pathological thickening of the vascular wall [102].

Schematic representation of copper metabolism in the body, including absorption, storage, transport, and excretion. Dietary copper is absorbed by enterocytes, where Cu²⁺ is reduced and transported via proteins such as CTR1, STEAP, DCYTB, and ATP7A, and then carried in circulation by HSA and Transcortin. In hepatocytes, copper is taken up via CTR1 for incorporation into enzymatic pools or is transported by CP and HSA. Excretion occurs through the bile duct, with ATP7B and MT/GSH mediating copper transport into bile.

Conversely, copper deficiency contributes to pathology via distinct mechanisms. It impairs the activity of SOD1, exacerbating intracellular oxidative stress and sensitizing cardiomyocytes to damage [12, 103]. Furthermore, by reducing CCO activity and compromising oxidative phosphorylation, copper deficiency compels cardiomyocytes to rely more heavily on anaerobic glycolysis, thereby reinforcing the metabolic shift that underpins pathological reprogramming [104]. In summary, both excess and deficiency of copper converge to promote myocardial reprogramming and remodeling, highlighting copper homeostasis as a critical nodal point in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases.

GSH Metabolism and Cuproptosis in the Heart

GSH, a tripeptide composed of glycine, cysteine, and glutamic acid, is a pivotal hub in cellular defense, functioning as both a primary antioxidant and a crucial regulator of copper ion bioavailability [105]. Its cardioprotective role is mediated primarily through two synergistic mechanisms: direct copper chelation and maintenance of redox homeostasis [106].

Beyond simple chelation, GSH also acts as a molecular chaperone, facilitating the delivery of Cu⁺ to specific copper chaperones (e.g., ATOX1) and supporting their function, particularly in copper export [107]. Crucially, the GSH/Glutaredoxin 1 system maintains the reduced state of cysteine residues within the copper-binding motifs of the transporters ATP7A and ATP7B, which is essential for their copper-transport activity [108].

These dual roles converge to inhibit cuproptosis. Mitochondrial GSH sequesters copper, preventing its binding to lipoylated proteins, such as DLAT, thereby blocking the aberrant protein oligomerization that drives this cell death pathway [109]. Consequently, intracellular GSH depletion increases the free copper pool, promotes protein oligomerization, and heightens sensitivity to copper-mediated cell death [110].

Under cardiac stress conditions, such as I/R injury, HF, or drug toxicity, GSH depletion initiates a vicious cycle of damage. The resulting increase in free copper exacerbates oxidative stress and proteotoxicity, further depleting GSH pools and impairing its metal-binding capacity [111, 112]. This cycle is amplified by copper's ability to catalyze the oxidation of catecholamines, generating additional toxic quinones and ROS that contribute to cardiotoxicity [113].

Notably, GSH's cardioprotective role extends beyond cuproptosis. As an essential cofactor for GPX4, GSH reduces lipid peroxides and inhibits ferroptosis [114]. However, this function can be compromised during copper overload, as Cu²⁺ binding to the cysteine residues of GPX4 promotes its ubiquitination and autophagic degradation, thereby disrupting lipid peroxide metabolism and sensitizing cells to ferroptosis [65]. This finding reveals a complex interactive network between copper dyshomeostasis, oxidative stress, and distinct programmed cell death pathways involved in cardiac pathology.

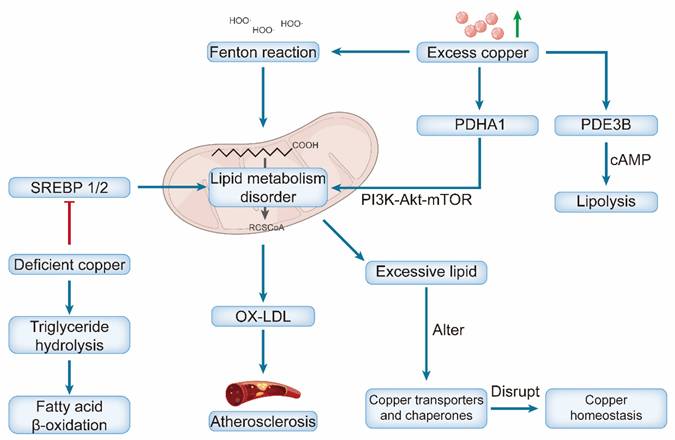

Lipid Metabolism and Cuproptosis in the Heart

Copper and lipid metabolism exhibit complex bidirectional interactions that critically influence the development and progression of cardiovascular diseases [115]. Dysregulation of one pathway often propagates dysfunction in another, establishing a vicious cycle that amplifies cellular injury and ultimately drives disease progression [116].

Copper exerts a profound influence on lipid metabolism, with both deficiency and excess producing distinct but detrimental effects [117]. Copper deficiency primarily disrupts lipid homeostasis by impairing the activation of key transcription factors, sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBP-1 and SREBP-2), which regulate fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis [88]. This disruption leads to suppressed lipogenesis and failure to maintain normal lipid homeostasis. Furthermore, copper deficiency concurrently promotes triglyceride hydrolysis and enhances fatty acid β-oxidation, creating a state of metabolic imbalance that contributes to pathology [118]. These disturbances, compounded by impaired mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, ultimately contribute to dyslipidemia—characterized by elevated serum triglycerides, LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), and total cholesterol—which accelerates pathological processes such as atherosclerosis and fatty liver disease [119, 120].

Copper Overload promotes cardiomyocyte injury by inducing oxidative stress, which in turn disrupts lipid metabolism [36]. The hydroxyl radicals produced via copper-catalyzed Fenton reactions mediate oxidative damage, primarily by oxidizing LDL into oxidized LDL (ox-LDL), which serves as a key driver of atherosclerotic plaque formation [121]. Moreover, copper influences lipid signaling by modulating the activity of phosphodiesterase PDE3B, an enzyme that hydrolyzes cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) to regulate lipolysis [122]. The cuproptosis-related gene PDHA1 may serve as a node linking these pathways, regulating lipid metabolism through its interaction with the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway [123] (Figure 5).

The lipid composition and fluidity of cell membranes affect the efficiency of the primary copper importer SLC31A1 (CTR1), thereby influencing the intracellular copper balance [124]. Excessive lipid accumulation disrupts copper homeostasis by altering the expression and localization of key copper transporters and chaperones [125]. The lipid microenvironment can also modulate susceptibility to cuproptosis. Under certain conditions, it may synergize with copper chaperones to facilitate efficient copper transport, thereby preventing cuproptosis [126]. More broadly, alterations in lipid metabolism, such as those mediated by short-chain fatty acids (e.g., butyric acid), can influence cell death pathways by modulating the expression of copper-related genes [127]. This establishes a feedback loop, as copper is an essential cofactor for numerous lipid metabolic enzymes; thus, initial copper deficiency can directly disrupt lipid homeostasis, which, in turn, further perturbs copper handling [116].

Central Role of Mitochondrial Metabolism in Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiac Cuproptosis

Mitochondrial metabolism serves a dual role in the cardiovascular system: it is the primary energy source for cardiomyocytes and a central integrator of overall cardiac health, and its dysfunction is a key driver of disease pathogenesis [128]. This centrality is underscored by the heart's exceptional dependence on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, which supplies approximately 95% of the ATP required for contraction [23]. Consequently, mitochondrial dysfunction has been identified as a central contributor to the onset and progression of various cardiovascular diseases, including HF, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, and atherosclerosis. The progressive decline in mitochondrial function, characterized by impaired ATP synthesis, excessive ROS production, and structural abnormalities, triggers a vicious cycle involving energy crises, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses, ultimately accelerating cardiomyocyte death [129, 130].

Dual effects of copper dyshomeostasis on lipid metabolism and atherosclerotic progression. Excess copper triggers the Fenton reaction, which induces mitochondrial lipid metabolism disorders. It also modulates PDHA1 and PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling to promote lipid metabolism disorders and PDE3B (promoting cAMP-mediated lipolysis). Excessive lipids further disrupt copper transporters/chaperones, forming a vicious cycle. Accumulated lipids drive OX-LDL production, ultimately leading to atherosclerosis. Conversely, deficient copper impairs SREBP 1/2 activity, reducing triglyceride hydrolysis and fatty acid β-oxidation (also contributing to lipid dysregulation).

At the molecular level, this dysfunction mediates pathology via several interconnected pathways. The mitochondrial electron transport chain (particularly Complexes I and III) is a major site of ROS generation. Beyond directly damaging mitochondrial components, ROS oxidize LDL to form ox-LDL, which promotes atherosclerosis by driving macrophage-to-foam cell formation [131, 132]. ROS can activate pro-inflammatory pathways, such as NF-κB, thereby inducing cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, apoptosis, and myocardial fibrosis, which further exacerbate cardiac structural and functional impairments [133].

Mitochondrial calcium (Ca²⁺) homeostasis disorder represents another crucial mechanism that exhibits close crosstalk with the ROS pathway. As a key regulator of ATP synthesis, Ca²⁺ modulates enzymes such as pyruvate dehydrogenase. Abnormal Ca²⁺ influx impairs energy production and activates caspase proteins, initiating the intrinsic apoptotic pathway and accelerating cardiomyocyte loss [134, 135]. Notably, excessive ROS can further exacerbate calcium homeostasis disorders by damaging the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca²⁺-ATPase and mitochondrial calcium uniporter, forming a malignant cascade of “excessive ROS-calcium imbalance-energy crisis” [136].

Of particular relevance, the heart is exquisitely vulnerable to copper imbalance owing to its profound reliance on mitochondrial energy production—organelles central to both copper homeostasis and the execution of cuproptosis [75, 137]. The initiation of cuproptosis critically depends on mitochondrial oxidative stress, as the oxidation of lipoyl groups on target proteins is a prerequisite for their high-affinity binding to Cu⁺, which drives toxic protein aggregation [3]. The accumulated Cu⁺ catalyzes intramitochondrial Fenton-like reactions, generating a burst of mtROS and amplifying oxidative stress. This creates feed-forward cycles that exacerbate cuproptosis: mtROS oxidize cytosolic GSH, releasing bound Cu⁺, and may upregulate the copper importer CTR1 via pathways such as NF-κB, increasing copper influx [65]. The resulting oxidative stress promotes Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission, mPTP opening, and membrane depolarization, thereby amplifying apoptotic signaling [52, 138]. The copper-induced ROS burst, coupled with disrupted TCA cycle-derived GSH precursors, leads to irreversible GSH depletion [108, 139]. This inactivates GPX4, halting lipid peroxide clearance and driving cell death [140].

Conversely, copper deficiency impairs cardiac mitochondria via distinct mechanisms. It disrupts the copper chaperone system (e.g., COX17, SCO1/SCO2), drastically reducing CCO biosynthesis and activity. This compromises ATP production and myocardial oxygen consumption rate, which is vital for contractile function [46, 141]. Deficiency also impairs PGC-1α, the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Notably, both its loss and uncontrolled overexpression are destructive, highlighting the need for precise regulation to maintain cardiac metabolism [142, 143]. Biochemically, these failures manifest as enlarged and degenerated mitochondria with loss of cristae, driving pathological cardiac remodeling [144]. A self-amplifying vicious cycle lies at the heart of this pathology. Pre-existing mitochondrial dysfunction due to aging, diabetes, or ischemia creates a permissive environment for cuproptosis by depleting GSH and reducing SOD2 activity, thereby compromising the organelle's ability to chelate copper and neutralize mtROS [145, 146]. This expands the labile Cu⁺ pool and lowers the threshold for cuproptosis initiation. In turn, cuproptosis inflicts further mitochondrial damage, disrupting membrane integrity and metabolic pathways [147]. This reciprocal relationship establishes a bidirectional causal link that accelerates the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases (Figure 6).

To counteract this vicious cycle, the heart is dependent on a robust mitochondrial quality-control system. This system replenishes healthy mitochondria through biogenesis, maintains network integrity via dynamics (fusion/fission), and clears damaged units through mitophagy [148]. Given their pivotal roles, targeting mitochondrial metabolism and copper homeostasis presents a promising strategy for novel therapeutic interventions in several cardiovascular diseases.

Cell-type-specific Cuproptosis in Cardiovascular System

The cardiovascular system comprises diverse cell types—including cardiomyocytes, ECs, VSMCs, and fibroblasts—each exhibiting distinct susceptibilities and responses to cuproptosis [149]. This heterogeneity is primarily determined by three interlinked factors: mitochondrial abundance, metabolic activity, and intrinsic copper handling capabilities. Consequently, cell types with high mitochondrial respiration, the primary target of copper toxicity, are disproportionately vulnerable [80].

Cardiomyocytes are the primary site of copper-induced injury because of their immense reliance on mitochondrial metabolism. The high density of mitochondria provides numerous targets for copper binding to lipoylated TCA cycle enzymes, directly disrupting the energy supply vital for contraction [75]. This intrinsic vulnerability is compounded by a weak copper export system, characterized by low expression of ATP7A/B transporters, which facilitates toxic accumulation [100]. In pathologies such as myocardial I/R injury, this confluence of factors leads to extensive cuproptosis, directly worsening systolic function [150].

ECs exhibit significant susceptibility, which is dictated more by their physiological context than their metabolic rate. Their direct contact with circulating copper and pro-oxidants (e.g., ox-LDL), combined with limited copper export capacity, creates a precarious copper balance [151, 152]. Given their role as central regulators of vascular homeostasis, EC cuproptosis can initiate widespread dysfunction, impairing barrier integrity and vasoreactivity [153].

The susceptibility of VSMCs is not fixed but is a direct function of their phenotypic state. Differentiated contractile VSMCs are relatively resistant. In contrast, synthetic, proliferative VSMCs—which dominate pathologies such as atherosclerosis—undergo a metabolic shift toward glycolysis and possess reduced antioxidant defenses, rendering them highly vulnerable to cuproptosis [154, 155]. This phenotypic targeting makes cuproptosis a potential modulator of vascular remodeling.

Fibroblasts are the most resistant cell type, protected by their low mitochondrial content and high expression of copper-buffering proteins, such as MTs [12]. However, this resilience does not render them inert. Instead, they are activated by damage-associated molecular patterns released from neighboring cardiomyocytes or ECs undergoing cuproptosis. Thus, paradoxically, fibroblast resistance fuels chronic disease progression by promoting pathological fibrosis [156].

The cell-type-specific impact of cuproptosis creates a dualistic injury pattern: it directly causes acute loss of contractile and endothelial function by eliminating cardiomyocytes and ECs, while simultaneously driving chronic maladaptive remodeling through the activation of resistant VSMCs and fibroblasts [154, 157]. This refined understanding underscores the necessity of cell-type-targeted therapeutic strategies that either protect vulnerable cells or modulate the response of resistant cells in cardiovascular diseases.

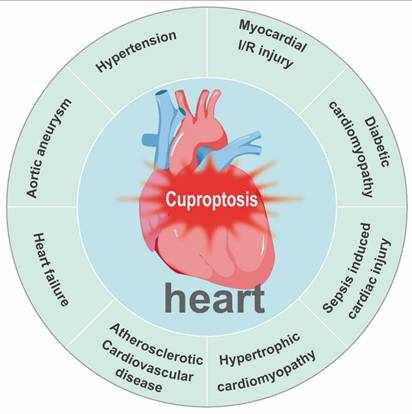

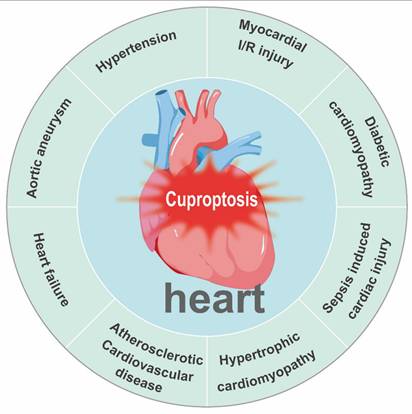

Role of Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Cardiovascular Disease

Copper acts as a quintessential “double-edged sword” in cardiovascular biology. Although it serves as an essential cofactor for critical enzymes governing antioxidant defense, energy production, and structural integrity, its dysregulation—manifesting as either deficiency or excess—is a common pathogenic thread across diverse cardiovascular conditions. These include myocardial I/R injury, diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM), sepsis-induced cardiac injury, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, HF, aortic aneurysm (AA), and hypertension (Figure 7). In each of these pathologies, disrupted copper homeostasis contributes to disease progression through distinct but convergent molecular mechanisms (Table 2).

Key cuproptosis molecular changes in cardiovascular diseases

| Disease/condition | FDX1 | DLAT | SLC31A1 (CTR1) | ATP7A/B expression | Key pathological outcome | Key evidence and proposed mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial I/R injury | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | Increased cardiomyocyte cuproptosis; larger infarct | Reperfusion triggers intense oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to coordinated upregulation of copper uptake and cuproptosis execution, resulting in secondary cardiomyocyte death. | [17] |

| Doxorubicin induced cardiotoxicity | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ATP7B ↓ | Mitochondrial injury and HF progression | Doxorubicin directly targets mitochondria, inducing severe oxidative stress and clearly activating the FDX1/DLAT-mediated cuproptosis pathway. | [74] |

| Diabetic cardiomyopathy | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | Impaired contractility and myocardial fibrosis | Hyperglycemia and metabolic disorders cause persistent mitochondrial stress, creating a pro-cuproptotic environment. The coordinated upregulation accelerates cardiomyocyte loss and fibrosis. | [169] |

| Sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy | ↑ | - | ↑ | Systemic inflammation and oxidative stress can activate FDX1 in the heart, leading to myocardial injury and functional impairment. | [270] | ||

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | ↑ | - | ↑ | ATP7A↑ | Endothelial dysfunction | In vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, inflammation and oxidative stress can activate cuproptosis, promoting cell death. | [187] |

| Heart failure | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ATP7A↑ | Progressive failure of the pump function | Heart failure and fibrosis of the heart were more obvious, suggesting the existence of a large number of cardiomyocyte loss. | [100] |

| Aortic aneurysm | ↓ | ↑ | - | - | Elastic fiber rupture, loss of smooth muscle cells | Cuproptosis is activated in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), leading to VSMC loss, which weakens the aortic wall. | [271] |

| Hypertension | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ATP7A↓ | Cardiac hypertrophy and myocardial fibrosis | Pressure overload leads to hypertrophy and mitochondrial dysfunction | [12] |

Copper dyshomeostasis in heart disease via mitochondrial pathways. Excess copper enters via CTR1, and excess ROS reduces GSH and drives OX-LDL production, contributing to atherosclerosis, Drp1-mediated fission, mPTP opening, and ultimately cuproptosis. Copper deficiency impairs mitochondrial biogenesis (PGC-1α) and disrupts COX assembly (via COX17, SCO1, and SCO2), resulting in bioenergetic failure due to ATP deficiency.

Cuproptosis is associated with major cardiac and vascular diseases, including myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, diabetic cardiomyopathy, sepsis-induced cardiac injury, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, heart failure, aortic aneurysm, and hypertension.

Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion Injury

Copper homeostasis is critically involved in the pathophysiology of myocardial I/R injury, with both deficiency and excess exacerbating damage through distinct mechanisms [158]. The acute inflammatory and oxidative stress that characterizes I/R injury is profoundly influenced by cellular copper status [159].

Copper deficiency impairs the heart's intrinsic defense mechanisms, thereby exacerbating I/R injury. It disrupts antioxidant defenses by reducing the activity of copper-dependent enzymes, such as CCS, leading to uncontrolled oxidative stress and intensified inflammatory responses [160, 161]. Chronic deficiency may elevate the baseline risk of ischemia by impairing vascular elasticity (via compromised LOX function) and promoting platelet aggregation [162]. Mechanistically, aberrant copper homeostasis during I/R impairs Fe-S cluster integrity, increases ROS production, and depletes GSH, culminating in synergistic proteotoxic and oxidative damage [160]. Supporting this, therapeutic strategies aimed at correcting deficiencies or restoring copper-dependent signaling have shown promise. In preclinical models of I/R injury, copper supplementation improves functional recovery by mitigating oxidative damage and enhancing mitochondrial bioenergetics [96]. In animal models, low-dose copper sulfate intake exerts potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-proliferative effects, attenuating I/R-induced tissue damage [163]. Similarly, controlled administration of copper ions can protect against tissue death by mitigating oxidative stress and inflammation, as evidenced by reduced lipid peroxidation and enhanced antioxidant reserve levels [164].

In contrast, copper overload causes damage through direct cytotoxic mechanisms. Excess copper can promote ferritin depletion and disrupt iron metabolism, thereby sensitizing cardiomyocytes to ferroptosis, a process that synergistically aggravates I/R injury [67]. This is supported by clinical observations; serum copper and CP levels rise post-myocardial infarction, indicating a stress response that, when excessive, may transition from a compensatory mechanism to a contributor of damage [165]. In summary, maintaining copper levels within a strict physiological range is paramount for mitigating I/R injury. Deficiency compromises intrinsic defensive capacity, whereas overload directly instigates oxidative and proteotoxic stress, including crosstalk with ferroptosis [166]. Therapeutic interventions must be precisely calibrated to restore homeostasis without inducing toxicity.

Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Diabetic cardiomyopathy

DCM is characterized by a pathological triad of cardiomyocyte death, interstitial fibrosis, and structural remodeling, culminating in HF [167]. Beyond the established mechanisms, a pivotal contributor to DCM pathogenesis is the disruption of systemic and cellular copper homeostasis, which primarily inflicts damage through the aberrant compartmentalization of copper within cardiac tissues [80].

The imbalance in copper metabolism in DCM presents a paradox. Systemic diabetes is associated with elevated plasma and urinary copper concentrations; however, the myocardium exhibits a marked reduction in copper content [168]. This discrepancy arises from defective myocardial copper handling, as evidenced by impaired expression and trafficking of key copper chaperones, which disrupts mitochondrial copper delivery in diabetic hearts [169]. The consequent sequestration of redox-active Cu²⁺ in the extracellular compartment and certain intracellular pools is a key mediator of cytotoxicity and cardiotoxicity in diabetes [51, 170]. Evidence from human studies and experimental models has linked cuproptosis to DCM. Mechanistically, high-glucose-induced AGEs promote cuproptosis in cardiomyocytes by upregulating SLC31A1 expression, which drives pathogenic Cu⁺ accumulation [80]. This extracellular and mislocalized intracellular copper exacerbates DCM through multiple pathways, activating the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway and amplifying oxidative stress, collectively promoting extracellular matrix deposition and fibrotic remodeling [171].

Given that direct coronary perfusion of low-concentration copper impairs cardiac function, dysregulation of copper homeostasis presents a clear and actionable therapeutic target. Accordingly, the copper chelator triethylenetetramine (TETA) has shown efficacy in markedly improving cardiac performance in preclinical models of DCM [80]. These findings underscore the fact that the core pathology stems from dysregulated copper transport and tissue distribution, not dietary copper intake [169]. Consequently, the therapeutic promise for DCM lies not in generic copper restriction but in strategies capable of rectifying this specific copper mislocalization. Approaches such as targeted chelation or restoration of chaperone function present a rational and promising avenue for halting DCM progression.

Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Sepsis-induced Cardiac Injury

Sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction is a primary cause of death and a major determinant of poor long-term outcomes [172]. Its pathogenesis involves excessive oxidative stress, dysregulated inflammatory cascades and profound mitochondrial damage [173]. Beyond these established factors, emerging evidence suggests that the disruption of copper homeostasis and the induction of cuproptosis are critical integrative mechanisms that potentially link systemic inflammatory-metabolic stress to direct cardiomyocyte death [174].

The relevance of this pathway is underscored by the significant dysregulation of cuproptosis-related genes in experimental models of septic cardiomyopathy [126]. The septic milieu itself—characterized by a cytokine storm and metabolic acidosis—acts as a potent upstream disruptor of copper homeostasis, priming the heart for copper-dependent injury [175]. This dysregulation is systemically reflected by a marked elevation in CP, a key copper-transporting acute-phase protein and a recognized clinical biomarker of sepsis [176]. However, the pathophysiological role of elevated CP levels may be dualistic. Although it has protective antioxidant functions, its surge may also alter copper kinetics, potentially increasing the delivery of redox-active copper to tissues or disrupting its cellular utilization, thereby paradoxically exacerbating copper-mediated toxicity in cardiomyocytes [177]. The elucidation of cuproptosis as a mechanism connecting inflammatory, metabolic, and mitochondrial damage to cardiomyocyte death opens new therapeutic avenues. Consequently, targeting this pathway—for instance, by modulating systemic copper distribution or using specific cuproptosis inhibitors—represents a promising strategy for cardioprotection in sepsis.

Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Copper deficiency is a well-established causative factor of cardiac hypertrophy, which manifests as concentric thickening of the ventricular walls and interventricular septum, resembling pressure-overload hypertrophy [178]. This pathology is primarily driven by severe mitochondrial dysfunction, which impairs energy production and triggers compensatory hypertrophic responses [179]. This process is exacerbated by dysregulated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and ROS generated via the Fenton reaction, collectively promoting maladaptive remodeling [180].

In a pressure overload-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy model, COX17 deletion inactivated CCO. This mitochondrial respiratory defect likely secondarily impairs MFN1-mediated mitochondrial fusion, potentially through mechanisms involving energy depletion or elevated oxidative stress [52]. Similarly, mutations in the SCO2 gene impair mitochondrial function and can cause cardiomyopathy, underscoring the critical role of copper delivery systems [181]. Beyond bioenergetics, copper ions are essential cofactors for specific signaling pathways. For instance, copper is required for the activation of MEK1 kinase, and disruption of this copper-dependent signaling contributes directly to myofibrillar disorganization and pathological hypertrophy [182, 183].

In the context of dietary copper deficiency, supplementation can restore cardiac copper levels. This restoration leads to improved mitochondrial health, enhanced CCO activity, angiogenesis (via VEGF signaling), and attenuation of cardiac hypertrophy [35, 178]. In cases of specific chaperone deficiencies (e.g., SCO2 mutations), copper-histidine therapy can improve cardiac function by restoring copper availability [184]. Targeting the downstream effectors of copper-dependent pathways is another strategy. For instance, MEK1 inhibitors have been shown to improve cardiac function and reverse myocardial fibrosis and hypertrophy [185]. In pathological states where localized or systemic copper excess contributes to hypertrophy, copper chelators can alleviate oxidative stress and subsequent remodeling [12].

Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

Atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease of the arterial wall, is characterized by the accumulation of lipids, inflammatory cells, and extracellular matrix, leading to plaque formation [186]. Copper homeostasis plays a complex, context-dependent role in this pathology, with both excess and deficiency contributing to disease progression via distinct mechanisms [187, 188].

Intracellular copper accumulation is a key feature of atherosclerosis. In atherosclerotic cells, such as ox-LDL-treated macrophages, copper levels are significantly elevated (by approximately 62%), providing a catalyst for redox reactions [154]. Through the Fenton reaction, redox-cycling copper ions potently catalyze hydroxyl radical formation, causing DNA damage and propagating lipid peroxidation [3]. Serum Cu²⁺ also drives the oxidation of LDL to form copper-ox-LDL, a key ligand that binds to the LOX-1 receptor on ECs to initiate plaque formation [189]. Furthermore, copper stimulates acute-phase proteins and activates the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB via ROS generation. This cascade promotes vascular inflammation, a process further amplified by upregulated CP expression [190].

Paradoxically, copper-dependent processes can also impair VSMC accumulation within the neointima, thereby affecting plaque stability [191, 192]. Moreover, copper homeostasis critically regulates the migration of VSMCs. The release of free copper ions, facilitated by transporters such as ATP7A and ATOX1, induces neointimal thickening following vascular injury, contributing directly to lesion development [193, 194]. In human studies, the expression level of the copper transporter SLC31A1 was directly correlated with atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability [42].

The pathogenic role of copper is context-dependent and exhibits a U-shaped risk curve. As described above, excess copper drives oxidative and inflammatory injuries. Conversely, copper deficiency elevates the risk of atherosclerosis by increasing cholesterol levels and reducing the activity of the copper-dependent antioxidant enzyme SOD1. This diminishes the overall antioxidant defenses and reduces NO bioavailability, leading to endothelial dysfunction [187]. The intertwined dysregulation of copper and iron metabolism further exacerbates the disease by promoting apoptosis in lipid-rich foam cells and VSMCs, which are particularly vulnerable to metal-dependent cell death [195, 196].

Epidemiological evidence shows that a high dietary copper intake is associated with a reduced incidence of coronary heart disease [39]. In animal models of copper deficiency, copper supplementation mitigated atherosclerotic lesion progression, as evidenced by reductions in lesion area, endothelial cell death, and plasma cholesterol levels [188]. Conversely, given the pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory effects of excess copper within plaques, preclinical studies have reported that strategies utilizing copper chelators may hold potential for attenuating plaque progression, although this requires further investigation. Additionally, copper-related DNA methylation alterations are linked to an elevated risk of acute coronary syndrome, suggesting an epigenetic role in the disease [197, 198].

Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Heart Failure

HF, a complex clinical syndrome characterized by significant functional impairment and high morbidity, stems from impaired cardiac contractility and/or ventricular filling [199]. A growing body of evidence underscores the critical role of disrupted copper homeostasis in its pathogenesis, wherein both excess and deficiency of copper significantly contribute to disease progression [30].

A meta-analysis conducted by Liu et al. [200] confirmed that elevated serum copper levels have been repeatedly are associated with an increased risk of HF. A meta-analysis of 1,504 individuals confirmed a positive association between high serum copper levels and HF [201]. Clinically, elevated copper levels and their carrier protein CP are significant predictors of adverse outcomes, including mortality, in patients with HF [202]. The underlying pathophysiology involves intracellular copper accumulation in cardiomyocytes, which directly induces cuproptosis [100]. Copper overload impairs mitochondrial electron transport, leading to excessive ROS production and a diminished antioxidant capacity. This is notably exacerbated by increased hydrogen peroxide production at the flavin site of mitochondrial complex IV [203]. The resultant oxidative damage triggers an inflammatory response characterized by the upregulation of acute-phase proteins, such as CP, further exacerbating cardiac dysfunction [204].

Paradoxically, copper deficiency worsens HF. Experimental studies have demonstrated that a copper-deficient diet exacerbates myocardial dysfunction in HF models [205]. In mouse models, copper deficiency impairs cardiac function, manifesting as reduced diastolic and systolic performance alongside a diminished inotropic response to beta-adrenergic stimulation, which compromises the heart's ability to adapt to stress [206].

This dual pathophysiology suggests the need for targeted therapeutic strategies. In states of copper overload, interventions that remove excess copper or restore normal cellular copper transport have shown promise in improving cardiac and mitochondrial function in preclinical studies [51]. In contrast, copper supplementation can fully restore cardiac function and normalize the β-adrenergic response in deficiency states [206]. In summary, maintaining precise copper homeostasis is essential for cardiac function. Therapeutic strategies that correct specific imbalances—whether through chelation in overload or supplementation in deficiency—hold significant promise for mitigating HF progression.

Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Aortic Aneurysm

AA, a life-threatening pathological dilation of the aortic wall and the ninth leading cause of death globally, arises from a complex interplay of factors, including inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress [207]. Emerging evidence firmly establishes that the disruption of copper homeostasis is a significant contributor to this process, driving aortic wall degeneration through interconnected pathways involving oxidative damage, inflammation, vascular dysfunction, and metabolic defects [208].

A pivotal initiating event is the downregulation or dysfunction of the key copper exporter, ATP7A. This defect leads to intracellular copper accumulation, exacerbating local oxidative stress and promoting aneurysm progression. Part of this effect is mediated by the upregulation of miR-125b, which amplifies copper-dependent pro-inflammatory signaling [209]. The accumulated copper ions function as potent catalysts for destructive processes within the aortic wall. They directly drive lipid peroxidation and inhibit essential enzymes, compromising vascular integrity [210]. Furthermore, copper imbalance disrupts the critical equilibrium that governs NO synthesis and degradation. As NO is a central regulator of vascular tone and remodeling, this disruption promotes the pathological dilation characteristic of aneurysms [211]. Underlying mitochondrial defects, often linked to disturbances in the TCA cycle, can be worsened by copper imbalance, further contributing to the energetic deficit and cellular stress that propel AA progression [212]. The delineation of these copper-mediated pathways has revealed promising therapeutic targets. Strategies aimed at correcting copper transport (e.g., by restoring ATP7A function) or mitigating the downstream consequences of excess copper (e.g., using targeted antioxidants) could potentially slow or halt aortic wall degeneration.

Copper Homeostasis and Cuproptosis in Hypertension

Clinical and experimental evidence confirms a U-shaped relationship between copper levels and blood pressure, indicating that both copper deficiency and excess are associated with a higher prevalence of hypertension [213]. This duality reflects the distinct pathogenic mechanisms at each extreme of copper homeostasis.

On the one hand, copper deficiency promotes hypertension primarily through impaired antioxidant defense and vascular dysfunction. Deficiency inactivates the copper-dependent antioxidant enzyme SOD1, leading to increased vascular oxidative stress. This oxidative environment uncouples endothelial NO synthase, reducing NO bioavailability and impairing vasodilation—a direct pathway to increased vascular resistance [214, 215]. Furthermore, as copper is a physiological inhibitor of angiotensin-converting enzyme, its deficiency disinhibits the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, further exacerbating hypertension [216, 217]. Consistent with this mechanistic link, lower blood copper levels have been observed in hypertensive animal models [215].

Copper dysregulation and excess copper also contribute to disease progression. In the vasculature, cuproptosis directly induces EC death and drives VSMCs toward a pro-inflammatory synthetic phenotype. This dual insult exacerbates endothelial dysfunction and promotes pathological vascular remodeling and sclerosis, creating a vicious cycle that elevates blood pressure [198, 218]. In the heart under pressure overload, intracellular copper accumulation can trigger cardiomyocyte cuproptosis via FDX1 activation, leading to lipoylated protein aggregation and mitochondrial damage, thereby exacerbating cardiac injury [12].

Population-based studies have corroborated this complex relationship. A cross-sectional study reported demographic variations and a potential independent association between serum copper and hypertension [219]. Notably, the protective negative association between dietary copper intake and myocardial infarction appears particularly strong among patients with hypertension, underscoring the clinical importance of maintaining optimal copper status in this high-risk group [39]. In summary, precise copper homeostasis is crucial for maintaining normal vascular tone and cardiac health, and deviations in either direction contribute to the pathogenesis and complications of hypertension.

Clinical Application of Copper Targeting Strategy for Cardiovascular Disease

Targeting dysregulated copper homeostasis represents a promising frontier in cardiovascular therapy, offering a mechanistic approach that is distinct from conventional treatments. Current strategies aim to restore balance through two principal means: chelation to mitigate copper overload or supplementation to correct deficiency, both with the goal of re-establishing metabolic equilibrium. In contrast, conventional therapies, such as β-blockers, statins, and ACEIs/ARBs, primarily target neurohormonal pathways, lipid metabolism, and hemodynamics [220] (Table 3). Therefore, modulating copper homeostasis and cuproptosis addresses a novel pathogenic axis that is not directly targeted by existing first-line drugs, suggesting the potential for synergistic or personalized therapeutic strategies.

Copper Chelators

Copper chelators are therapeutic agents that bind copper ions to form stable complexes, alleviating cardiovascular pathologies, primarily by reducing the labile intracellular copper pool. This inhibits cuproptosis and associated oxidative damage by preventing ROS generation [80] (Table 4). Furthermore, the reduction in bioavailable copper impairs the function of copper-dependent proteins and signaling pathways, including SOD1, copper chaperones (ATOX1, ATP7A), and transcription factors, such as HIF-1α and NF-κB [221]. The overarching cardioprotective effect is achieved through the restoration of mitochondrial integrity and function, as evidenced by the recovery of key components (e.g., SCO1, CCO, and SOD1) and upregulating the biogenesis regulator PGC-1α [51, 204]. The benefits of this approach have been validated in several disease models. Copper chelation inhibits pivotal VSMC migration in intimal hyperplasia [194] improves recovery after myocardial infarction [222] and reduces neointimal formation and atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice [223]. Overall, by chelating excess copper, these agents help to restore metabolic homeostasis and protect cardiovascular cells.

Characteristics of conventional cardiovascular drugs and copper metabolism-related drugs

| Class of agent | Representative drugs | Core mechanism | Indications | Key adverse effects | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional drugs | Metoprolol (β-blocker) | Blocks β-adrenergic receptors to inhibit sympathetic nervous system excitation | Hypertension, heart failure, and arrhythmia | Bradycardia, fatigue, and bronchospasm | [272] |

| Conventional drugs | Enalapril (ACE inhibitor) | Inhibits angiotensin-converting enzyme, reducing the production of the potent vasoconstrictor angiotensin II | Hypertension, heart failure, cardiac protection after myocardial infarction, and diabetic nephropathy | Dry cough, angioedema, hyperkaliemia, and kidney damage | [273] |

| Conventional drugs | Losartan/valsartan (ARB) | Blocks the binding of angiotensin II to its receptor | Hypertension, heart failure, and diabetic nephropathy | Hyperkaliemia and kidney damage | [274] |

| Conventional drugs | Atorvastatin (statin) | Inhibits HMG-CoA reductase and lowers LDL cholesterol | Atherosclerosis, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) | Muscle soreness or myopathy, elevated liver enzymes, and risk of new-onset diabetes | [275] |

| Copper metabolism-Targeted agents | TTM (trientine tetrahydrochloride) and TETA (trientine) | Chelates labile Cu⁺ and reduces bioavailable copper | Copper metabolic disorders | Copper deficiency, bone marrow suppression, and kidney damage | [276] |

| Copper metabolism-Targeted agents | Elesclomol (copper ionophore, repurposed) | Binds to extracellular copper ions (Cu²⁺) to form complexes that enter cells | Cancer treatment | Oxidative stress-related toxicity and mitochondrial dysfunction | [58] |

Copper chelators for use in clinical trials

| Conditions | Phases | Primary Objective | Results | Enrolled | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Status | Organizing Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilson Disease | The period of the day best correlated with 24 h urinary copper excretion | 30 | NCT06430359 | Recruiting | France | ||

| Head and Neck Cancer | II | The safety and efficacy of penicillamine (a common copper chelator) | 10 | NCT06103617 | Recruiting | China | |

| Wilson Disease | Assess copper parameters in participants with Wilson disease | 64 | NCT02763215 | Completed | United States/ Austria/Germany/ Poland/United Kingdom | ||

| Wilson Disease | The clinical efficacy and safety of trientine | 48 | NCT03299829 | Completed | Taiwan | ||

| Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis | I/II | The safety of the administration of a copper chelating agent, tetrathiomolybdate | The primary endpoint is safety with secondary endpoints including change in pulmonary function, exercise capacity, and quality of life | 23 | NCT00189176 | Completed | United States |

| Psoriasis Vulgaris | II | The safety and efficacy of Tetrathiomolybdate in psoriasis therapy | 10 | NCT00113542 | Completed | United States | |

| Wilson Disease | I/II | the safety of single IV doses of UX701 | 82 | NCT04884815 | Active, not recruiting | United States/Canada/ Portugal/Spain/ United Kingdom | |

| Wilson Disease | Not Applicable | A single daily treatment with trientine is as effective or better than a patient's current maintenance therapy | The primary endpoint is the demonstration of equivalence to a patient's prior therapy. Secondary endpoints include: 1) demonstration of stability or improvement in parameters of copper metabolism; 2) improvement in adherence to therapy; and 3) no progression of liver disease | 8 | NCT01472874 | Completed | United States |

| Epithelial Ovarian Cancer | I/II | copper chelator in conjunction with cytotoxic agents to conquer platinum-resistance | 18 | NCT03480750 | Completed | Taiwan |

Tetrathiomolybdate (TTM) is a highly selective copper chelator that prevents copper accumulation and toxicity in vivo by sequestering excess copper ions [224]. TTM inhibits their uptake and delivery by chaperone proteins to downstream cuproenzymes, such as LOX, inducing functional defects in these enzymes [225]. The efficacy of TTM stems from its ability to modulate copper bioavailability across diverse cardiovascular disease models. It attenuates atherosclerosis in ApoE⁻/⁻ mice by reducing bioavailable copper and suppressing vascular inflammation [198] and protects against AAs in ATP7A-deficient mice by inhibiting endothelial ROS [209]. In the heart, TTM improves myocardial injury in diabetes and after ischemia by enhancing mitochondrial protein activity and reducing infarct size [80]. It also alleviates chronic stress-induced myocardial fibrosis by regulating the cardiac copper levels [49]. Additionally, TTM inhibits TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB and AP-1, leading to the suppressed expression of adhesion molecules (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) and the chemokine MCP-1. This attenuates endothelial activation and contributes to the inhibition of atherosclerotic progression [226, 227].

TETA, typically administered as a dihydrochloride salt, restores cardiac function by rectifying copper homeostasis and repairing mitochondrial integrity. Its primary mechanism involves restoring the activity of key mitochondrial enzymes, such as SOD1, CCS, and CCO, thereby re-establishing metabolic function [51]. Animal studies have validated this efficacy, showing that TETA therapy enhances cardiac pumping efficiency and normalizes the levels of copper, copper-binding proteins, and CCO in the myocardial tissue [51]. Furthermore, it ameliorates hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and reverses diabetes-induced mitochondrial damage by restoring the expression and function of crucial cardiac energy metabolic proteins [37, 228].

Small-molecule Inhibitors of Copper Chaperone Proteins

The clinical utility of conventional copper chelators is limited by dose-dependent toxicities, primarily stemming from systemic copper deficiency and off-target chelation of essential metals, such as zinc and iron. This underscores the pressing need for novel agents capable of selectively modulating intracellular copper homeostasis without systemic depletion [46]. Emerging strategies focus on precise molecular targets within copper transport machinery.

A key approach involves the development of small molecules that directly inhibit intracellular copper trafficking. The drug DCAC50 exemplifies this strategy by binding to the copper chaperones ATOX1 and CCS, thereby disrupting copper delivery and its dependent signaling without harming normal cells [229, 230]. The copper chaperone ATOX1 is a particularly compelling target in this context. Beyond its cytoplasmic transport role, ATOX1 is critically involved in vascular pathology; it promotes VSMC migration—a key process in neointimal and atherosclerotic lesion formation—and recruits inflammatory cells [93, 194]. Mechanistic insights have revealed that ATOX1 translocates to the nucleus in response to inflammatory cytokines or copper ions [93]. Moreover, in TNF-α-stimulated ECs, the copper-dependent ATOX1-TRAF4 interaction promotes nuclear translocation and initiates ROS-dependent inflammatory responses, solidifying this axis as a promising therapeutic target [45].

In contrast, a distinct pharmacological strategy employs copper ionophores, such as elesclomol. Instead of inhibiting copper flux, these agents form complexes with copper to facilitate cellular uptake. Their pro-oxidative action exploits copper to induce selective toxicity in target cells, representing a different therapeutic logic that is useful in specific contexts [231, 232]. Together, these approaches—precise inhibition of copper chaperones and conditional use of copper ionophores—represent innovative strategies for targeting copper dyshomeostasis in cardiovascular and other diseases.

Copper Ionophore

Copper ionophores are small molecules that enhance intracellular copper bioavailability by shuttling copper across the cell membrane. Primarily used to treat research overload or exploit copper toxicity in therapy, this class includes disulfiram and pyrithione [233].

Their intracellular effects are complex and context dependent. Some ionophores can increase NO levels and reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, indicating their anti-inflammatory potential [234]. Others, such as members of the 8-hydroxyquinoline family, can synergize with SOD transporters to mitigate intracellular ROS, thereby protecting against oxidative stress and apoptosis [235]. A central therapeutic challenge is their lack of cell-type specificity, which leads to off-target effects [236]. To overcome this limitation, targeted delivery systems are being developed. For example, Su et al. [237] conjugated N-acetylgalactosamine to a copper ionophore to create Gal-Cu, a liver-targeting system. This design enhances copper delivery to hepatocytes while reducing exposure to nontarget organs, thereby minimizing systemic toxicity.

However, the use of ionophores remains a pharmacological double-edged sword. Cells possess adaptive homeostatic mechanisms, such as upregulation of the copper efflux transporter ATP7B, to counteract increased influx [238]. Excessive ionophore administration can overwhelm these defenses, leading to systemic copper poisoning, characterized by hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and hematopoietic suppression [239]. Therefore, the therapeutic window for ionophores is narrow, and precision in their delivery and dosing is paramount.

Limits and Challenges