10

Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2021; 17(3):683-688. doi:10.7150/ijbs.56037 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Depression and its relationship with quality of life in frontline psychiatric clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: a national survey

1. Department of Psychiatry, Xiamen Xianyue Hospital, Xiamen, China.

2. Unit of Psychiatry, Institute of Translational Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Macao SAR, China.

3. Centre for Cognitive and Brain Sciences, & Institute of Advanced Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Macau, Macao SAR, China.

4. The National Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders & Beijing Key Laboratory of Mental Disorders Beijing Anding Hospital & the Advanced Innovation Center for Human Brain Protection, Capital Medical University, School of Mental Health, Beijing, China.

5. Department of General Surgery, Beijing Liangxiang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China.

6. School of Nursing, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China.

7. Global and Community Mental Health Research Group, New York University (Shanghai), Shanghai PR China.

8. School of Global Public Health, New York University, NY, USA.

#These authors contributed equally to the work.

Received 2020-11-17; Accepted 2021-1-7; Published 2021-1-30

Abstract

This was a national survey that determined the prevalence of depressive symptoms (depression thereafter) and its relationship with quality of life (QOL) in frontline clinicians working in psychiatric hospitals in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Depression and QOL were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire nine items (PHQ-9) and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire-brief version (WHOQOL-BREF), respectively. Multivariable logistic regression analyses and analysis of covariance were used. A total of 10,516 frontline clinicians participated in this study, of which, 28.52% (n=2,999) met screening criteria for depression. Compared to those without depression, clinicians with depression had a lower quality of life (F (1, 10515) =2874.66, P<0.001). Higher educational level (OR=1.225, P=0.014), if the number of COVID-19 patients in the hospital catchment area surpassed 500 (OR=1.146, P=0.032), having family/friends/colleagues who were infected (OR=1.695, P<0.001), being a current smoker (OR=1.533, P<0.001), and longer working hours (OR=1.020, P=0.022) were independently associated with higher risk of depression. Living with family members (OR=0.786, P<0.001), and being junior clinicians (OR=0.851, P=0.011) were independently associated with lower odds of depression. The results showed that depression was common in frontline psychiatric clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Timely assessment and effective interventions of depression for frontline clinicians in psychiatric hospitals were warranted.

Keywords: COVID-19, depression, psychiatric clinician, quality of life, prevalence

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first reported in China, and then was rapidly found in more than 200 countries and territories [1]. To reduce rapid transmission, mass quarantine measures were adopted. Many public services including public transports were suspended [2]. Such containment measures were associated with a range of psychological problems, such as anxiety, panic disorder, and depression [3-5]. For instance, one study found that depressive symptoms (depression thereafter; 30.3%), anxiety (36.4%) and stress symptoms (32.1%) were common in the general population during the COVID-19 outbreak [6]. With the rapid increase in the number of confirmed and suspected COVID-19 cases and insufficient preventive measures and personal protective equipment, uncertainty about the new virus and the known high risk of infection may have triggered common mental health problems in frontline health professionals [7]. A survey reported that the prevalence of depressive symptoms was 50.4% and anxiety symptoms was 44.6% in health professionals who had previous exposure with COVID-19 [8]. Another study found that medical professionals reported insomnia (38.4%), anxiety (13.0%), depression (12.2%), and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (5.3%) during the COVID-19 outbreak [9].

Compared to those working in general hospitals, clinicians in psychiatric hospitals are presumed to work in a highly stressful clinical environment which makes them more vulnerable to higher risk of mental health problems [10, 11]. Patients with severe mental illness in psychiatric hospitals often live in a crowded clinical environment compared to patients residing in general hospitals. Psychiatric patients may have limited intellectual ability / capacity to comply with infection control measures to protect themselves due to their poor mental health status and active symptomatology. Consequently, psychiatric patients are at heightened risk of susceptibility of the disease during the COVID-19 outbreak [12]. Indeed, hundreds of psychiatric inpatients and many mental health professionals were infected with COVID-19 in China, and South Korea [13, 14]. All of these aforementioned factors could increase the likelihood of mental health problems, particularly depression, among frontline clinicians in psychiatric hospitals since they have the most frequent direct contact with psychiatric patients on a daily basis. Aside from their heavy workload, clinicians may also experience fear of contagion and transmitting the virus to their family members and colleagues. Quality of life (QOL) is a widely used comprehensive health outcome measure involving many aspects such as physical and mental health, family relationship, education, employment, sense of security [15]. Psychiatric problems particularly depression are negatively associated with QOL [16-18].

To alleviate the negative effect of depression on mental wellbeing and quality of care, it is essential to explore the pattern of depression in frontline psychiatric clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, to date, no relevant studies have been published, which gave us the impetus to conduct a large-scale study to examine the prevalence of depression and its relationship with QOL in frontline psychiatric clinicians in China.

Methods

Study design

This national, anonymous survey was carried out from 15 to 20 March, 2020. Considering the risk of infection, face-to-face assessments were not adopted. Instead, online assessment with the QuestionnaireStar program has been used based on convenience sampling as recommended previously in other epidemiological studies [19, 20]. There were over 1 billion WeChat users in China and it has been widely used in continuing education for psychiatric clinicians. With the help of the Psychiatric Working Committee of the Chinese Nursing Association and the Chinese Society of Psychiatry, the Quick Response code (QR code) and the link to the assessment instruments were delivered to all member panels in each province by WeChat. The panel members then distributed the QR Code and the link to all psychiatric hospitals/units in their respective areas. Psychiatric clinicians in these hospitals/units completed the assessment on a voluntary basis. To be eligible, participants needed to be: 1) aged 18 years or older; 2) frontline clinicians (including psychiatric nurses, nursing assistants and psychiatrists) working in psychiatric departments/hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic; The University of Macau Research Ethics Panel approved the study protocol, and all participants provided informed consent.

Assessment tools

Demographic and clinical data were collected, including gender, age, marital status, educational level (e.g., primary and secondary school vs. college education and above). In addition, we also asked about the total number of local COVID-19 patients in participants' hospital catchment area (at the provincial level), whether they provided clinical services for COVID-19 patients, and having family, friends, or colleagues infected with the COVID-19.

We administered the Patient Health Questionnaire nine items (PHQ-9) to measure the presence of depression [21] , with each item scoring from “0” (not at all) to “3” (almost every day) [22]. Having a PHQ-9 total score of ≥5 was considered 'having depression' [23]. Specifically, a PHQ-9 total score of 5-9 indicated 'mild depression', 10-14 'moderate depression', 15-19 'moderately severe depression' [21]. The total score ranged from 0-27. QOL was evaluated with the sum of the first two items (overall QOL) of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire-brief version (WHOQOL-BREF) that has been validated in Chinese populations [24, 25]. Higher total scores indicated higher QOL [26].

Statistics

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 20.0. Comparisons between clinicians with and without depression in demographic and clinical factors were performed using Chi-square tests, independent samples t-tests, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests, as appropriate. Independent associated factors of depression were examined in multivariable logistic regression analyses using the “enter” method. Depression was the dependent variable, and all variables with a P value of < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were included as independent variables. The overall QOL between clinicians with and those without depression was compared with analysis of covariance. Significance level was set at 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Altogether, 10,516 frontline clinicians fulfilled the entry criteria and participated in this study. The PHQ-9 mean score was 3.27 (SD=4.29). Of the frontline clinicians, 28.52% (95% CI: 27.66%-29.38%; 2,999/10,516) suffered from depression. Among the 2,999 clinicians with depression, 20.3% (2,137/10,516) reported mild depression, 5.5% (583/10,516) moderate depression, 1.8% (187/10,516) moderately severe depression, and 0.9% (92/10,516) severe depression. Demographic characteristics of the whole sample separated by depression were presented in Table 1.

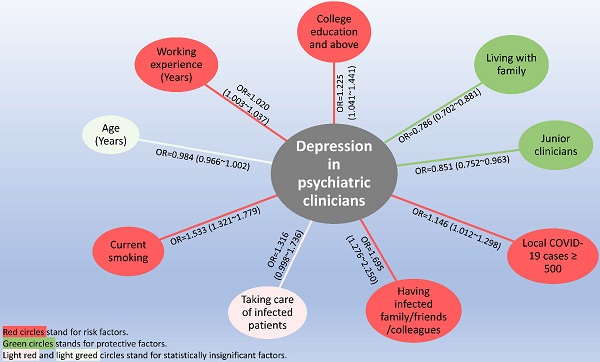

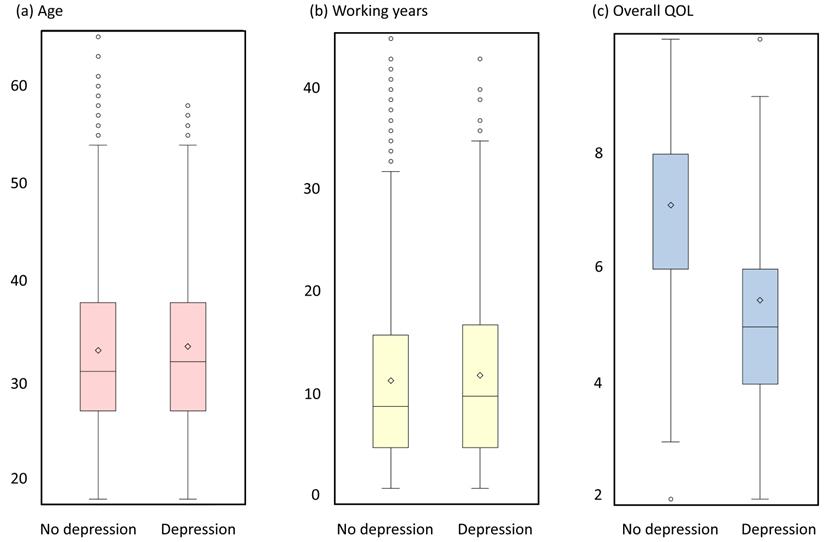

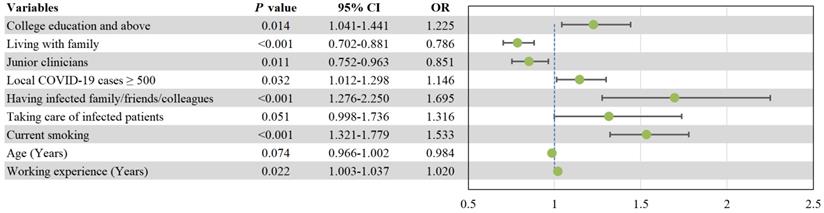

Table 1 shows that depression was significantly associated with age, educational level, living with family, clinicians' rank, and length of working experience, current smoking behavior, total number of local COVID-19 patients, having family/friends/colleagues who were infected, direct patient care of infected patients. ANCOVA revealed that clinicians with depression had lower QOL compared with those without depression (F (1, 10515) =2874.66, P<0.001). Multivariable analysis found that higher educational level (OR=1.225, P=0.014), if the total number of local COVID-19 patients in residence area surpassed 500 (OR=1.146, P=0.032), having infected family/friends/colleagues (OR=1.695, P<0.001), current smoking behavior (OR=1.533, P<0.001), and longer working experiences (OR=1.020, P=0.022) were independently associated with higher odds of depression. Living with family (OR=0.786, P<0.001), and being junior clinicians (OR=0.851, P=0.011) were independently associated with lower risk of depression (Figure 2).

Discussion

We found that 28.52% (95% CI: 27.66%-29.38%) of frontline clinicians reported depression, which was higher than the corresponding figures in most (e.g., 14.9% using the Depression Status Inventory (DSI) [27]; 16.67% using the Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) [28]), but not all studies (e.g., 47.25% using the SDS [29]) among psychiatric clinicians in China. Similar studies were also conducted in other countries, but only a few reported the prevalence of depression among clinicians in psychiatric hospitals. A study in Japan using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies for Depression Scale (CES-D) [30] showed that depression among male and female psychiatric clinicians were 36.4% and 37.2%, respectively. Nonetheless, direct comparisons should be conducted with caution due to different measurements and cut-off values used to assess depression between studies.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Variables | Total (N=10,516) | No depression (N=7,517) | Depression (N=2,999) | χ2 | df | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||

| Male gender (ref = female) | 1,635 | 15.5 | 1,145 | 15.2 | 490 | 16.3 | 1.999 | 1 | 0.157 |

| Married (ref = not married) | 7,273 | 69.2 | 5,231 | 69.6 | 2,042 | 68.1 | 2.260 | 1 | 0.133 |

| College education and above | 9,635 | 91.6 | 6,861 | 91.3 | 2,774 | 92.5 | 4.187 | 1 | 0.041 |

| Living with family | 8,629 | 82.1 | 6,234 | 82.9 | 2,395 | 79.9 | 13.740 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Junior clinicians (ref = senior) | 7,341 | 69.8 | 5,326 | 70.9 | 2,015 | 67.2 | 13.652 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Experience of fighting SARS | 948 | 9.0 | 666 | 8.9 | 282 | 9.4 | 0.771 | 1 | 0.380 |

| Working in tertiary hospitals | 6,564 | 62.4 | 4,713 | 62.7 | 1,851 | 61.7 | 0.873 | 1 | 0.350 |

| Working in inpatient department | 9,642 | 91.7 | 6,881 | 91.5 | 2,761 | 92.1 | 0.775 | 1 | 0.379 |

| Shift duty clinicians | 7,719 | 73.4 | 5,482 | 72.9 | 2,237 | 74.6 | 3.039 | 1 | 0.081 |

| Local COVID-19 cases ≥ 500 | 1,361 | 12.9 | 927 | 12.3 | 434 | 14.5 | 8.709 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Family/friends/colleagues infected | 213 | 2.0 | 121 | 1.6 | 92 | 3.1 | 22.964 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Taking care of infected patients | 235 | 2.2 | 146 | 1.9 | 89 | 3.0 | 10.317 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Current smoking | 854 | 8.1 | 542 | 7.2 | 312 | 10.4 | 29.294 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t/Z | df | P | |

| Age (Years) | 33.25 | 8.40 | 33.14 | 8.50 | 33.50 | 8.16 | -1.974 | 10514 | 0.048 |

| Working experience (Years) | 11.66 | 9.10 | 11.51 | 9.21 | 12.04 | 8.83 | 4.71* | — | <0.001 |

| Total QOL score | 6.64 | 1.60 | 7.12 | 1.42 | 5.46 | 1.39 | 54.288 | 10514 | <0.001 |

Bolded values: <0.05; SD: standard deviation; COVID-19: Corona Virus Disease 2019; SARS: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; QOL: Quality of Life; * Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Box plots of age, working years and overall QOL.

Independent correlates of depression by multiple logistic regression analysis. CI: confidential interval; OR: odds ratio; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

Frontline clinicians play a pivotal role in health services by rendering clinical care, advocating health education, and contributing to rehabilitation [31, 32]. Compared with their counterparts working in other specialties, clinicians in psychiatric hospitals are more prone to suffer from psychological distress, such as burnout and depression because psychiatric patients may exhibit severe psychiatric symptoms, such as aggressive behaviors and suicidality [33]. In addition, inadequate health resources are persistent problems in psychiatric hospitals in China [34, 35]. More significantly, stigma still exists towards the field of psychiatry in China, and thus, clinicians working in psychiatric hospitals tend to have a relatively low social status [36].

Clinicians in psychiatric hospitals might end up with excessive workload during the COVID-19 pandemic as they were the first-line staff responsible for taking care of their inpatients [33]. To make the situation worse, many COVID-19 patients suffered from psychiatric comorbidities [37], as such, psychiatric response teams were urgently established in many areas and provided services for these infectious patients with psychiatric symptoms in designated infectious hospital [38, 39], which may have further lowered the nurse-patient ratio in psychiatric hospitals. All these factors could immediately elevate the likelihood of depression among clinicians working in psychiatric hospitals.

In this study, clinicians with higher educational level and with more clinical experience in senior ranks reported a higher prevalence of depression. Apart from a heavy clinical workload, senior clinicians and experienced staff with higher educational backgrounds are primarily responsible for supervision of junior colleagues and conducting research [11]. These senior clinicians are also more likely to provide clinical service to patients with severe psychiatric symptoms due to their clinical expertise [40]. Their multi-functional role and extensive scope of service provision alongside with preceptorship and research responsibilities may trigger higher levels of stress among senior clinicians, resulting in a higher risk of depression.

As expected, clinicians who lived in greatly affected areas by COVID-19 (e.g., with ≥ 500 COVID-19 patients), had family, friends or colleagues who were infected, and direct care of infected patients had higher likelihood of depression due to fear of infection, stress, and anxiety. All clinicians underwent a minimum of two-week's quarantine following their care for infected patients, which could further increase psychological distress due to fear of contagion and infect others. Clinicians living with families usually had better social support, and this could effectively lower the likelihood of depression and improve wellbeing [41]. We also found that smoking behavior was related to higher risk of depression, confirming previous findings [42, 43].

Clinicians with depression reported lower QOL, which supports previous findings in other populations [44, 45]. According to the distress/protection QOL model [46], QOL was determined by distressing (e.g., physical and mental distress) and protective factors (e.g., better health status). Due to the somatic and psychiatric symptoms associated with depression and their impact on daily life and functional outcomes, it was unsurprising that depressed clinicians had lower QOL.

Several limitations should be noted. First, causality between demographic and clinical variables and depression cannot be examined because of the cross-sectional design. Second, data were collected via an online self-reported survey; therefore, participants may have misunderstood some survey questions. Third, some factors related to depression in frontline clinicians, such as history of psychiatric illness, social support, negative life events, and type of clinical training, were not examined. Fourth, the classification of frontline clinicians working in psychiatric hospitals such as psychiatric nurses, nursing assistants and psychiatrists was not made as this could not be verified in an online survey. Therefore, direct comparisons of depression between different subpopulations could not be performed.

In conclusion, depression was prevalent in Chinese psychiatric clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Routine assessment and effective treatment of depression for frontline clinicians is warranted. To reduce the risk of mental health problems among psychiatric clinicians in future public health crises, health authorities could develop guidelines and expert consensus to address occupational health and safety conditions, and crisis psychological intervention and counseling for frontline health professionals [47]. In addition, it would be helpful to assist their families to handle daily life requirements and securing their financial status. The establishment of timely psychological services and the provision of on-site mental health services for frontline health professionals should also be considered.

Abbreviations

QOL: quality of life; PHQ-9: patient health questionnaire nine items; WHOQOL-BREF: world health organization quality of life questionnaire-brief version; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; DSI: depression status inventory; SDS: self-rating depression scale; CES-D: center for epidemiologic studies for depression scale.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The study was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project for investigational new drug (2018ZX09201-014), the Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (No. Z181100001518005) and the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00066-FHS).

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Deng CX. The global battle against SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1676-7

2. Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T. et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:228-9

3. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33:e100213

4. Kılınçel Ş, Kılınçel O, Muratdağı G, Aydın A, Usta MB. Factors affecting the anxiety levels of adolescents in home-quarantine during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2020: e12406.

5. Venugopal VC, Mohan A, Chennabasappa LK. Status of mental health and its associated factors among the general populace of India during COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2020: e12412.

6. Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS. et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 17

7. Pan X, Xiao Y, Ren D, Xu ZM, Zhang Q, Yang LY. et al. Prevalence of mental health problems and associated risk factors among military healthcare workers in specialized COVID-19 hospitals in Wuhan, China: A cross-sectional survey. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2020: e12427.

8. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N. et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976

9. Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Zhao WF, Xue Q, Peng M. et al. Mental Health and Psychosocial Problems of Medical Health Workers during the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020 p: 1-9

10. Lu Q, Zhong G. Depression in Psychiatric Nurses (in Chinese). China Journal of Health Psychology. 2015:204-6

11. Liu J, Bao L. Investigation and analysis of depression in psychiatric nurses and countermeasures (in Chinese). Hebei Medical Journal. 2006 p: 778-9

12. Tuna O, Enez Darcin A, Tarakcioglu MC, Aksoy UM. COVID-19 Positive Psychiatry Inpatient Unit: A unique experience. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2020;12:e12410

13. Shim E, Tariq A, Choi W, Lee Y, Chowell G. Transmission potential and severity of COVID-19 in South Korea. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;93:339-44

14. China News Weekly. About 80 doctors and patients at the Wuhan Mental Health Center were diagnosed with novel coronavirus pneumonia (in Chinese). 2020. Accessed 19 February. 2020

15. IESE Insight. Quality Of Life: Everyone Wants It, But What Is It? 2013. Accessed 4 September. 2013

16. Angermeyer MC, Holzinger A, Matschinger H, Stengler-Wenzke K. Depression and quality of life: results of a follow-up study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2002;48:189-99

17. Brenes GA. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in primary care patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:437-43

18. Sivertsen H, Bjorklof GH, Engedal K, Selbaek G, Helvik AS. Depression and Quality of Life in Older Persons: A Review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2015;40:311-39

19. Li F, Wu JF, Mai XH, Ning K, Chen KY, Chao L. et al. Internalized homophobia and depression in homosexuals: the role of self-concept clarity (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2016;24:475-9

20. Xi X, Liu YF. The appliation of Wechat platform and Wenjuanxing in cognitive training among psychiatric nurse, cleaning staff and patients (in Chinese). Nursing Practice and Research. 2017;14:114-7

21. Chen M, Sheng L, Qu S. Diagnostic test of screening depressive disorder in general hospital with the Patient Health Questionnaire (in Chinese). Chinese Mental Health. 2015;29:241-5

22. Cameron IM, Crawford JR, Lawton K, Reid IC. Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58:32-6

23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345-59

24. Harper A, Power M, Grp W. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551-8

25. Hao Y, Fang J, Power MJ, Wu S, Zhu S. The Equivalence of WHOQOL-BREF among 13 Culture Versions (in Chinese). Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2006: p:71-5.

26. Skevington SM, Tucker C. Designing response scales for cross-cultural use in health care: data from the development of the UK WHOQOL. Br J Med Psychol. 1999;72( Pt 1):51-61

27. Chen R, Meng H. An investigation on depression and anxiety emotion and characters of psychiatric nurses (in Chinese). Medical Information. 2011;05:261-2

28. Xiang L, He C, Fu L. The correlation between acquired wisdom level and anxiety, depression in psychiatric nurse (in Chinese). Henan Medical Research. 2016 p: 987-8

29. Zhou C, Wang Z, Li X, Han Q, Wang B. Investigation and analysis of depression in clinical and psychiatric nurses (in Chinese). Medical Journal of Chinese People's Health. 2004;16:588-9

30. Yoshizawa K, Sugawara N, Yasui-Furukori N, Danjo K, Furukori H, Sato Y. et al. Relationship between occupational stress and depression among psychiatric nurses in Japan. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2016;71:10-5

31. DeLucia PR, Ott TE, Palmieri PA. Performance in Nursing. Reviews of Human Factors & Ergonomics. 2009;5:1-40

32. He Z, Chen J, Pan K, Yue Y, Cheung T, Yuan Y. et al. The development of the 'COVID-19 Psychological Resilience Model' and its efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:2828-34

33. Xiang YT, Jin Y, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Cheung T. Tribute to health workers in China: A group of respectable population during the outbreak of the COVID-19. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1739-40

34. Zeng JY, An FR, Xiang YT, Qi YK, Ungvari GS, Newhouse R. et al. Frequency and risk factors of workplace violence on psychiatric nurses and its impact on their quality of life in China. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210:510-4

35. Li W, Yang Y, Liu ZH, Zhao YJ, Zhang Q, Zhang L. et al. Progression of Mental Health Services during the COVID-19 Outbreak in China. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1732-8

36. Li P, Liu Y, Cao X. Investigation on the correlation between current status of professional identity and job involvement in psychiatric nurses (in Chinese). Shanghai Nursing Journal. 2019;019:57-9

37. Xiang YT, Zhao YJ, Liu ZH, Li XH, Zhao N, Cheung T. et al. The COVID-19 outbreak and psychiatric hospitals in China: managing challenges through mental health service reform. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2020;16:1741-4

38. China National Radio. The 16th batch of Chongqing medical team supporting Wuhan is composed of psychologists (in Chinese). 2020. Accessed 24 February. 2020

39. Sina Guangdong. The first batch of 30 psychologists from Guangdong supporting hubei have joined "the epidemic war" (in Chinese). 2020. Accessed 27 February. 2020

40. Su Y. Investigation and analysis of anxiety and depression in psychiatric nurses (in Chinese). Clinical Journal of Chinese Medicine. 2017;9:8-9

41. Lei H, Zhang W. The relationship between life quality and social support of the nurse in psychiatric hospital (in Chinese). Chinese Journal of Coal Industry Medicine. 2016 19

42. Wang J, Okoli CTC, He H, Feng F, Li J, Zhuang L. et al. Factors associated with compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020;102:103472

43. Li XH, An FR, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Chiu HFK, Wu PP. et al. Prevalence of smoking in patients with bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and schizophrenia and their relationships with quality of life. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8430

44. Gao T, Xiang YT, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Mei S. Neuroticism and quality of life: Multiple mediating effects of smartphone addiction and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2017;258:457-61

45. Teles F, Amorim de Albuquerque AL, Freitas Guedes Lins IK, Carvalho Medrado P, Falcao Pedrosa Costa A. Quality of life and depression in haemodialysis patients. Psychol Health Med. 2018;23:1069-78

46. Voruganti L, Heslegrave R, Awad AG, Seeman MV. Quality of life measurement in schizophrenia: reconciling the quest for subjectivity with the question of reliability. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:165-72

47. Xiang YT, Zhao N, Zhao YJ, Liu Z, Zhang Q, Feng Y. et al. An overview of the expert consensus on the mental health treatment and services for major psychiatric disorders during COVID-19 outbreak: China's experiences. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:2265-70

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Dr. Yu-Tao Xiang, 3/F, Building E12, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Avenida da Universidade, Taipa, Macau SAR, China. Fax: +853-2288-2314; Phone: +853-8822-4223; E-mail: xyutlycom; or Dr. Feng-Rong An, Beijing Anding Hospital, China; E-mail: afrylmcom.

Corresponding authors: Dr. Yu-Tao Xiang, 3/F, Building E12, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Avenida da Universidade, Taipa, Macau SAR, China. Fax: +853-2288-2314; Phone: +853-8822-4223; E-mail: xyutlycom; or Dr. Feng-Rong An, Beijing Anding Hospital, China; E-mail: afrylmcom.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact