10

Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-2288

Int J Biol Sci 2026; 22(1):280-307. doi:10.7150/ijbs.121356 This issue Cite

Review

Mechanical Microenvironment in Tumor Immune Evasion: Bidirectional Regulation Between Matrix Stiffness and Immune Cells and Its Therapeutic Implications

1. College of First Clinical Medicine, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan 250014, China.

2. College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shandong Second Medical University, Weifang, 261000, China.

3. Faculty of Chinese Medicine, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau 999078, China.

4. Department of Oncology, Weifang Traditional Chinese Hospital, Weifang 261000, China.

*Jing Ai and Huayao Li have contributed equally to this work and share the first authorship.

Received 2025-7-10; Accepted 2025-11-7; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Immune evasion remains a major obstacle to effective cancer immunotherapy. While the regulatory mechanisms of the tumor biochemical microenvironment are relatively well-characterized, the role of its mechanical microenvironment—particularly pathologically elevated matrix stiffness—in immune evasion remains to be fully elucidated. Immune cells, as dynamic responders within the tumor microenvironment, are not merely passive recipients of mechanical signals but also active participants in driving pathological matrix stiffening. This review focuses on the elevated matrix stiffness resulting from abnormal deposition and crosslinking of the tumor extracellular matrix, systematically elucidating how it impairs immune cell function and drives immune evasion through physical barriers and mechanotransduction. Additionally, we further propose an innovative concept: the "matrix stiffness-immune cell bidirectional regulatory axis." Dissecting this regulatory loop provides an essential mechanical perspective for understanding immune evasion and offers a conceptual framework for developing matrix-targeted strategies to enhance immunotherapy. By integrating current evidence, this review aims to clarify the role of this bidirectional axis and to identify novel therapeutic targets and strategies that may improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapies.

Keywords: Immune evasion, Matrix stiffness, Extracellular matrix, Immune cell function, Immunotherapy.

Introduction

Tumor cells evade immune surveillance and elimination by altering intrinsic properties or exploiting the host's immunosuppressive and dysregulated responses, ultimately forming clinically detectable tumors—a phenomenon termed immune evasion [1]. As a major challenge in current immunotherapy, one of the reasons for the progression of immune evasion and therapeutic resistance lies in the dynamic regulation by the functional plasticity of immune cells [2]. During early tumorogenesis, nascent tumor lesions can be recognized and eliminated by both adaptive and innate immune systems. As the disease progresses, however, tumor cells collaborate with the tumor microenvironment (TME) to reprogram infiltrating immune cells toward exhausted or suppressive states—characterized by an increase in dysfunctional CD8⁺ T cells, expanded regulatory T cells (Tregs) infiltration, and impaired maturation and function of dendritic cells (DCs). These changes collectively drive the transition toward an immunosuppressive TME [1, 3]. Notably, the biomechanical properties of the TME, an emerging dimension of tumor biology, have been identified as pivotal drivers of immune evasion: matrix stiffness, solid stress, interstitial fluid pressure, and topological structure collectively mediate immunosuppression by impeding immune cell migration to tumor-infiltrated regions and disrupting anti-tumor immune cascades [4, 5]. Among these factors, increased matrix stiffness is one of the most prominent mechanical abnormalities in malignant tumors [6]. Not only does it facilitate tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, but it also significantly contributes to immune evasion, thereby reducing tumor sensitivity to immunotherapeutic interventions [7-9].

Elevated matrix stiffness is a hallmark biomechanical alteration in various malignancies, including breast cancer (BC), pancreatic cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Quantitative assessments of the elastic modulus reveal that tumor tissues exhibit substantially higher stiffness compared to the soft microenvironment of normal or benign tissues [10-13]. For example, the average stiffness of malignant breast tumors reaches approximately 153 kPa, markedly exceeding the typical range of 40-64 kPa observed in benign lesions [10]. This abnormal stiffening primarily results from excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and enhanced crosslinking [6, 14], contractile tension generated by tumor cells, and compressive stress caused by uncontrolled tumor growth [6, 15, 16]. These factors act synergistically to remodel the ECM architecture, ultimately leading to increased matrix stiffness. Significantly, aberrant ECM accumulation and lysyl oxidase (LOX)-mediated crosslinking represent the principal driving forces behind matrix stiffening [17-19]. This process is dynamically orchestrated by the interplay between cellular components—including tumor cells, immune cells, and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)—and acellular factors such as the hypoxic microenvironment [18, 20]. Such pathologically elevated matrix stiffness also forms a physical barrier that impedes immune cell infiltration [21-23] and impairs tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS)-mediated antitumor immunity [24]. This phenomenon, in which CAFs play a central role, is closely associated with the development of a desmoplastic reaction [22, 25], in which CAFs play a central role. Upon activation, CAFs undergo extensive proliferation and secrete abundant ECM components, contributing to enhanced ECM synthesis and remodeling during desmoplasia [26]. Consequently, CAFs, stromal cells, and the ECM converge to form dense connective tissue that envelops tumor nests [27, 28]. This physical barrier compromises immune cell trafficking to the tumor site and disrupts the formation of TLSs [24]. TLSs are lymph node-like aggregates that serve as critical hubs for the initiation and maturation of antitumor immune responses and are generally associated with favorable prognosis in multiple cancers [29]. Nonetheless, excessively high intratumoral matrix stiffness may disrupt TLS-driven antitumor immunity by compressing the extracellular space and restricting immune cell motility, thereby ultimately promoting immune evasion [24].

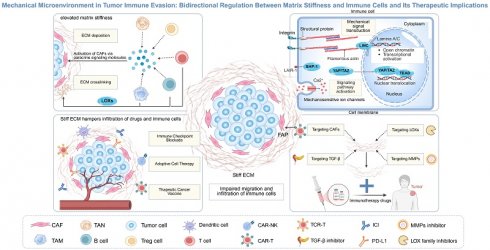

Importantly, as key executors of antitumor immunity, immune cells actively participate in ECM remodeling by dynamically sensing and responding to changes in tumor matrix stiffness through mechanotransduction signaling pathways [30]. Immune cells can directly or indirectly promote ECM deposition and crosslinking by secreting ECM-related proteins [31], collagen-modifying enzymes [12], and cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [32], thereby contributing to pathological matrix stiffening [33]. Beyond forming a physical barrier that impedes immune infiltration, current evidence indicates that mechanostimuli mediated by elevated matrix stiffness activate cell membrane receptors and mechanosensors—including integrins, mechanosensitive ion channels, and cytoskeletal components [34-37]. This biomechanical signaling cascade converts mechanical cues into biochemical responses, ultimately suppressing activation states, migratory capacities, and effector functions of key immune cells such as effector T cells, DCs, and Natural Killer (NK) cells, ultimately creating an immunosuppressive environment [38-40]. In summary, a bidirectional regulation is formed between matrix stiffness and immune cells, continuously exacerbating the immunosuppressive state and ultimately jointly promoting tumor immune evasion [4, 41, 42] (Fig. 1).

Although several existing reviews have addressed the regulatory effects of matrix stiffness on immune cells [43, 44], the specific mechanisms by which matrix stiffness modulates diverse immune cell functions—such as migration, proliferation, differentiation, and secretory activity—remain inadequately elucidated. In addition, given the dynamic nature of matrix stiffness evolution, immune cells can actively remodel matrix mechanical properties to establish bidirectional crosstalk. However, this critical mechanism has been insufficiently emphasized in current research efforts.

In this review, we systematically dissect the key roles of immune cells in the development of elevated matrix stiffness in tumors and explore the biomechanical mechanisms through which stiffness modulates immune cell functions to drive immune evasion. On this basis, we propose an innovative theoretical framework: the matrix stiffness-immune cell bidirectional regulation axis, offering a biomechanical perspective for understanding immune evasion. Although stiffness-based metrics hold great promise for tumor diagnosis, staging, and prognostic stratification [10, 38, 45], their translation into therapeutic strategies remains limited. Therefore, we further evaluate the impact of matrix stiffness on immunotherapy efficacy, review recent clinical advances in targeting stiffness to enhance therapeutic responsiveness, and propose a combinatorial strategy integrating stiffness-targeting agents with immunotherapy. This approach aims to open new avenues for overcoming immunotherapy resistance and to provide actionable targets for clinical intervention.

Main Text

1. Immune Cells Participate in Constructing the Hardened Fortress of the TME

The ECM constitutes a three-dimensional (3D) dynamic supramolecular network composed of collagen, elastin, proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and functional glycoproteins (e.g., fibronectin, laminins), exhibiting distinctive physical, chemical, and biomechanical properties [46, 47]. During tumor progression, aberrant deposition and excessive crosslinking of collagen and other ECM components serve as primary drivers of elevated matrix stiffness [17, 38, 48, 49]. This process does not occur in isolation but is co-regulated by cellular components—such as tumor cells, immune cells, and CAFs—as well as acellular factors including the hypoxic microenvironment, collectively driving alterations in the mechanical properties of the TME [18, 20]. Hypoxia, a hallmark of the TME, promotes excessive collagen synthesis and deposition by CAFs through hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-dependent mechanisms, while also inducing ECM-remodeling enzymes such as LOX to facilitate collagen cross-linking, ultimately leading to increased matrix stiffness [19, 50]. For instance, hypoxia upregulates LOX expression via the HIF-1α-miR-142-3p axis; LOX then catalyzes the formation of rigid collagen networks, further enhancing matrix stiffness [19]. This elevated stiffness, in turn, exacerbates intratumoral hypoxia [19, 50]. Beyond ECM modulation, the hypoxic microenvironment recruits immuno-suppressive cells—including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs)—thereby fostering an immune-evasive milieu [50].

Bidirectional regulation between matrix stiffness and immune cells. (A) Immune cells promote matrix stiffening by directly secreting extracellular matrix (ECM) components and cross-linking enzymes (e.g., lysyl oxidase (LOX)), or by activating cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) through paracrine signaling molecules such as transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). These actions lead to excessive ECM deposition and enhanced cross-linking, resulting in elevated matrix stiffness that forms a physical barrier, thereby impeding immune cell infiltration and migration. (B) Conversely, increased matrix stiffness modulates immune cell function through mechanosensors (e.g., integrins, mechanosensitive ion channels) and downstream effectors (e.g., YAP/TAZ, JAK/STAT), ultimately impairing the cytotoxicity of effector cells (e.g., CD8⁺ T cells and natural killer cells), disrupting antigen presentation by dendritic cells, and enhancing the immunosuppressive activity of regulatory T cells. This mechano-immunological crosstalk fosters an immunosuppressive niche that facilitates tumor immune evasion.

It is noteworthy that immune cells also play an important role in the dynamic regulation of the ECM [20, 31, 33, 51]. They can not only directly secrete ECM components but also activate CAFs by producing cytokines and chemokines, thereby indirectly promoting ECM deposition [17, 33]. Moreover, they can express collagen-modifying enzymes to regulate the spatial assembly process and stability of collagen [31], ultimately leading to an increase in matrix stiffness [33]. Intriguingly, immune cells exhibit a dual role in ECM remodeling: while they facilitate matrix stiffening via the above mechanisms, they also secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to degrade ECM components [31, 52-54]. This seemingly contradictory functionality underscores the dynamic nature of immune-stromal crosstalk [33]. Importantly, elevated matrix stiffness represents a dynamically regulated process throughout tumor progression and serves as a key biomechanical hallmark of aberrant ECM remodeling [18, 38] (Fig. 2).

1.1 Immune cell involvement in ECM deposition

In the pathological remodeling process of tumor ECM, abnormal deposition of matrix proteins occurs, leading to changes in the density, structural organization, and porosity of the matrix, with a significant increase in matrix stiffness [13]. Immune cells contribute to the elevated stiffness of the tumor matrix through two principal mechanisms that facilitate ECM deposition: firstly, via direct secretion of ECM components such as collagen, fibronectin, and osteopontin; and secondly, by indirectly promoting CAF-mediated matrix production through complex cytokine networks, including TGF-β and platelet-derived growth factor-B [31, 51, 55]. Significantly, TAMs play a critical role in this process by engaging in a positive feedback loop with the progressively stiffening matrix. This reciprocal interaction further drives sustained ECM hardening [56, 57].

The process of aberrantly increased tumor matrix stiffness. The tumor extracellular matrix (ECM) is structurally categorized into the basement membrane and the interstitial stroma. The basement membrane comprises components such as laminin, type Ⅳ collagen, and nidogen, whereas the interstitial stroma is enriched with type Ⅰ/Ⅲ collagen, proteoglycans, and diverse glycoproteins, critically contributing to the high stiffness characteristic of the tumor stroma. Tumor cells and infiltrating immune cells, including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), not only directly secrete matrix proteins but also activate cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) through the release of cytokines and chemokines. Activated CAFs, serving as the predominant source of interstitial ECM, extensively secrete and deposit ECM components. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) and lysyl oxidase-like (LOXL) family enzymes, secreted by TAMs, CAFs, and tumor cells, catalyze the crosslinking of ECM proteins. Concurrently, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) secreted by these same cell types degrade the ECM, thereby releasing latent transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Collectively, these processes drive the formation of a dense molecular network within the matrix, consequently elevating tumor matrix stiffness.

1.1.1 Direct secretion of ECM-associated factors by immune cells

Recent studies reveal TAMs as active ECM remodelers that directly synthesize and secrete osteopontin, fibronectin, proteoglycans, and various collagen types, thereby influencing the mechanical properties and structural integrity of tumor tissue [31, 55]. For instance, integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analyses in colorectal cancer models demonstrate that TAMs markedly upregulate gene expression and protein translation of type I (COL1A1/COL1A2), III (COL3A1), IV (COL6A1/COL6A3), and XIV (COL14A1) collagens. Depletion of TAMs results in widespread reduction of ECM proteins [55]. Similarly, Peng et al. confirmed the pivotal role of TAMs in ECM deposition through single-cell RNA sequencing [58], an effect amplified by mechanochemical coupling. In 3D models simulating the high-stiffness microenvironment of triple-negative BC, mechanically stressed M2-like TAMs exhibit upregulated expression positively correlating with aberrant deposition of basement membrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2 (Perlecan/HSPG2). This deposition further elevates matrix stiffness, which in turn promotes Perlecan/HSPG2 expression in M2-like TAMs via nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway activation, establishing a stiffness-amplifying feedback loop [56]. Thus, TAMs actively contribute to tumor matrix stiffening through direct collagen synthesis, with their secretory behavior mechanoregulated and engaged in reciprocal interactions with the mechanical microenvironment to perpetuate a vicious cycle.

Apart from TAMs, neutrophils have also been reported to actively contribute to ECM generation [59, 60]. For instance, a specific subset of neutrophils identified in skin tissue directly participates in the structural and mechanical regulation of barrier tissues through de novo synthesis of ECM components [59]. In models of myocardial infarction, neutrophils appear to promote ECM deposition in the ischemic heart via production of fibronectin and fibrinogen [60]. However, these findings have not yet been fully validated within the TME, highlighting a significant gap in current understanding. Nonetheless, whether other immune cells directly secrete ECM proteins remains largely unexplored, representing a novel avenue for future research.

1.1.2 Immune cell-mediated indirect promotion of ECM deposition via CAF activation

CAFs, the most abundant stromal cell population in the TME, serve as primary orchestrators of ECM remodeling and stiffness elevation. They achieve this through excessive production of structural ECM proteins (e.g., collagens type I, III, IV, V, laminin, fibronectin) and crosslinking enzymes such as LOXs [26, 61]. Immune cells—including TAMs, T cells, Tregs, TANs, and B cells—secrete cytokines such as CXC-motif chemokines, TGF-β, fibroblast growth factors, interleukins (ILs), and platelet-derived growth factors, which potently augment CAFs activity. Specifically, TGF-β activates CAFs via SMAD-dependent and -independent pathways, enhancing synthesis, secretion, and deposition of matrix proteins to promote matrix stiffening [20, 32, 51, 62, 63]. Acerbi et al. reported that in BC, TGF-β signaling intensity, matrix stiffness, and infiltrating activated TAMs exhibit positive mutual correlation [48]. High matrix stiffness potentiates SMAD signaling downstream of TGF-β and stimulates TAMs to produce elevated levels of active TGF-β1. TGF-β1 then induces CAFs to synthesize fibrillar collagens and collagen crosslinking enzymes, driving stiffness escalation [57]. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), TAM-derived C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 3 engages C-X-C chemokine receptor 2 on CAFs to induce myofibroblastic transdifferentiation, accelerating collagen type Ⅲ deposition [64].

In addition to TAMs, B cells derived from PDAC patients secrete the pro-fibrotic mediator platelet-derived growth factor-B, which directly stimulates collagen production by fibroblasts [51]. Additionally, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs)—web-like structures composed of DNA filaments decorated with histones and granule proteins released by TANs [65]—enhance the migratory capacity of hepatic stellate cells, promoting their recruitment to metastatic liver lesions and subsequent transformation into CAFs, thereby indirectly facilitating ECM synthesis and deposition [66]. This immune cell-initiated CAF activation, culminating in excessive ECM deposition and aberrant crosslinking, constitutes an important indirect mechanism of tumor matrix stiffening.

1.2 Immune cell involvement in ECM modification

The biomechanical properties of the ECM are governed by post-translational modifications—including hydroxylation, glycosylation, and crosslinking—which collectively contribute to its structural integrity, stability, and matrix stiffness [13, 17, 67]. Hydroxylation, catalyzed by prolyl 4-hydroxylases (P4Hs) and lysyl hydroxylases (PLODs) within the endoplasmic reticulum, represents an initial critical step that facilitates correct collagen folding into stable triple helices and serves as a key precursor for covalent cross-linking [68, 69]. P4H isoforms are frequently overexpressed in tumors and promote ECM remodeling, tumor cell invasion, and metastasis through HIF-1α-dependent expression [70]. Following hydroxylation, glycosylation of hydroxylysine residues further modulates collagen maturation and enhances its resistance to proteolytic degradation, thereby prolonging ECM persistence [17, 71]. After secretion and proteolytic processing, collagen fibers undergo cross-linking primarily mediated by LOXs, which oxidize lysine and hydroxylysine residues to generate reactive aldehydes that facilitate intermolecular covalent bond formation. In the tumor context, aberrant LOXs activity drives pathological stiffening through excessive cross-linking, severely compromising matrix deformability and serving as a major driver of stromal hardening [67, 72].

Beyond the roles of tumor cells and CAFs, immune cells also actively regulate post-translational modification of the ECM [31, 73]. TAMs directly overexpress collagen-modifying enzymes—including PLOD1/3, P4HA1, procollagen C-endopeptidase enhancer, and transglutaminase 1/2—to control collagen stability and spatial assembly, thereby enhancing crosslinking [55, 57, 73, 74]. Maller et al. demonstrated that TAMs directly drive fibrotic progression in invasive breast tumors by stimulating collagen crosslinking and matrix hardening [73]. Similarly, Xing et al. reported that high expression of collagen type I/LOX in HCC correlates positively with M2-like TAMs and lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2) levels. Their work further linked matrix stiffness to LOXL2 upregulation via the integrin β5-focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 and 2 (MEK1/2)-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling axis [12]. Other immune populations also contribute to ECM remodeling: B cells in PDAC express LOXL2 [51], while CD8⁺ T cells serve as a major source of LOX following chemotherapy in BC, mediating treatment-induced ECM remodeling in the lung [75]. These findings systematically illuminate how immune cells promote tumor stiffness through enzymatic ECM modification and cross-linking, providing a mechanistic rationale for therapeutic strategies targeting immune-stromal crosstalk.

1.3 Immune cells participate in ECM degradation

The ECM undergoes continuous remodeling through a dynamic process of constant synthesis and degradation, wherein the degradation of ECM components facilitates the replacement of the normal ECM architecture with a tumor-derived ECM matrix [17]. MMPs represent the principal enzyme family responsible for degrading collagen and other structural proteins within the ECM [76]. Based on substrate specificity and domain organization, MMPs are classified into several types, including collagenases (e.g., MMP-1, MMP-8, MMP-13), gelatinases (e.g., MMP-2, MMP-9), and membrane-type MMPs (MT-MMPs). Among these, MMP-2 and MMP-9 are the most extensively studied MMPs, as they facilitate tumor invasion and metastasis by degrading the ECM and basement membrane, thereby creating physical pathways for tumor dissemination [77]. Within the TME, both myeloid and lymphoid cells secrete MMPs; nonetheless, the types, levels, and functions of MMPs secreted exhibit cell-type specificity [31, 52-54]. Myeloid cells are significant contributors to MMP production. For instance, TANs secrete MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-8, whereas TAMs release MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-12, among others [31, 52, 53, 78]. Studies have demonstrated that MMPs secreted by these cells promote ECM degradation, angiogenesis, and tumor metastasis [31, 52, 53, 78]. In contrast, although T cells are capable of transcribing mRNAs for proteases such as MMP-9, MT1-MMP, and MT4-MMP, they exhibit markedly low cell surface protein expression [54]. Within the TME, MMP expression in T cells is primarily associated with facilitating migration and infiltration rather than broad ECM degradation [79]. These functional disparities underscore the diverse regulatory roles of immune cell-specific MMP expression in ECM remodeling and tumor progression.

MMP-mediated ECM degradation is a critical driver of tumor cell migration and invasion [17]. Although extensive proteolysis may transiently reduce local matrix stiffness [77] and could theoretically enhance immune cell infiltration, it concurrently liberates latent TGF-β and other bioactive fragments embedded within the matrix. The released TGF-β not only directly suppresses immune effector functions but also activates CAFs, prompting them to synthesize and deposit new matrix components [80-82]. This process ultimately leads to the progressive remodeling and replacement of the native ECM with a tumor-derived, pathologically altered stroma [42]. Interestingly, myeloid cells can also secrete tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1), which counteracts MMP activity [36, 83]. The dynamic balance between MMPs and TIMPs is regulated by tumor stage and microenvironmental signals [84]. Thus, the consequences of ECM degradation are highly context-dependent, shaped by the spatiotemporal patterns of protease activity, the composition of degradation products, and ongoing crosstalk with stromal cells.

2. The Tumor Immune Evasion Greenhouse Nurtured by Matrix Stiffness

Elevated matrix stiffness acts not only as a biomechanical driver of tumor malignancy but also as a key regulatory factor that induces an immunosuppressive TME and promotes immune evasion [7, 8]. Immune cells actively contribute to ECM deposition and cross-linking [55]. The resulting elevated matrix stiffness reciprocally modulates immune cell activation and effector functions through mechanotransduction pathways. This bidirectional "matrix stiffness-immune cell" crosstalk redefines the intrinsic logic of tumor stromal evolution and offers novel perspectives for understanding immune evasion and developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

First, densely crosslinked rigid matrices form physical barriers that impede the recruitment of effector immune cells, allowing tumor cells to escape immunosurveillance [23, 40]. Second, immune cells actively perceive and respond to stiffness variations through mechanotransduction [30], primarily mediated by membrane receptors and mechanosensors that globally activate immunosuppressive networks [35, 43]. For instance, mechanical stimuli induce conformational changes in adhesion complexes (e.g., integrin clusters), recruiting adaptor proteins to activate signaling cascades such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT) pathway. These forces propagate via the cytoskeleton to drive nuclear translocation of mechanosensitive transcription factors including Yes-associated protein (YAP)/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ). Meanwhile, mechanosensitive ion channels rapidly transduce physical cues into biochemical responses via secondary messengers (e.g., Ca²⁺ influx). Collectively, these mechanotransduction events orchestrate protein refolding, cytoskeletal reorganization, and nuclear shuttling of transcriptional regulators—ultimately modulating immune cell activation, differentiation, and effector functions [35, 85]. As a result, the cytotoxicity of T cells and NK cells is impaired, DCs exhibit impaired antigen presentation, and immunosuppressive cells such as TAMs and Tregs accumulate and activate [32, 43]. In summary, matrix stiffness impedes immune cell function via a dual mechanism involving physical barriers and mechanical signaling. This results in compromised antitumor immune responses and fosters an environment conducive to tumor immune evasion [4, 41]. Herein, we primarily focus on discussing the specific mechanisms through which matrix stiffness influences the function of immune cells.

2.1 Matrix stiffness modulates macrophage polarization and immunoregulatory functions

Macrophages exhibit high phenotypic and functional plasticity. Beyond presenting exogenous antigens, they secrete cytokines and growth factors to orchestrate immune responses. Within tumors, these cells are defined as TAMs. TME-derived signals drive TAM polarization toward classically activated (M1) or alternatively activated (M2) phenotypes, with M2-like TAMs exhibiting anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive functions [86, 87]. Accumulating evidence indicates that the biophysical properties of the ECM—notably matrix stiffness—exert significant regulatory effects on macrophage polarization and function [11]. Through multiple mechanotransduction signaling pathways, elevated matrix stiffness promotes M2-like polarization of macrophages and enhances their immunosuppressive activity. These alterations ultimately contribute to the impairment of CD8⁺ T cell function and foster tumor immune evasion [35, 42, 43, 57] (Fig. 3).

2.1.1 Matrix stiffness promotes M2 polarization

The process by which elevated tumor matrix stiffness drives macrophage polarization toward an M2 phenotype involves multiple interconnected layers, including mechanoreceptor activation, cytoskeletal-nuclear coupling, signaling cascades, and transcriptional reprogramming [11, 36, 56, 88, 89]. This regulation is initiated by mechanosensing and signal transduction. Integrins—core mediators of cell-ECM adhesion—play pivotal roles in stiffness-induced M2 polarization [11, 12, 36]. When macrophages adhere to high-stiffness polyacrylamide (PA) gels, conformational changes in integrin family receptors (e.g., integrin β5) lead to the recruitment of adaptor proteins such as talin and paxillin, followed by the assembly and activation of FAK, collectively forming focal adhesion complexes. This complex transmits mechanical signals to the cytoskeleton via myosin-assembled stress fibers [36, 85, 90]. The forces are subsequently relayed through the linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton complex into the nucleus, leading to nuclear flattening and upregulation of lamin A/C expression. This enhances chromatin accessibility at M2-associated gene promoters, facilitating binding of key transcription factors like signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) to activate pro-M2 transcriptional programs [36, 90]. Intriguingly, this mechanical-transcriptional regulation synergizes with biochemical signals such as IL-4/IL-13, and cooperatively drives the alternative M2 activation program [36, 90]. In HCC, elevated matrix stiffness activates the integrin β5-FAK-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 signaling axis, leading to upregulation of HIF-1α expression. This mechanotransduction pathway subsequently promotes the expression of M2 macrophage polarization markers and LOXL2, collectively enhancing M2-polarization of macrophages in the TME [12].

In addition to the integrin-cytoskeleton-nucleus axis, the activation of mechanosensitive ion channels provides another critical transduction pathway for matrix stiffness-mediated macrophage polarization [11, 89]. Studies using 3D stiffened hydrogel models have demonstrated that elevated matrix stiffness activates Piezo type mechanosensitive ion channel component 1 (Piezo1) and transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) mechanosensitive channels in macrophages, inducing extracellular Ca²⁺ influx [34, 89, 91]. Notably, Piezo1 responds to high-intensity mechanical stimuli by generating transient yet high-amplitude Ca²⁺ signals, whereas TRPV4 is sensitive to low-intensity, sustained mechanical cues and produces prolonged Ca²⁺ oscillations. TRPV4 often acts downstream of upstream mechanosensors such as Piezo1, primarily functioning as a Ca²⁺ signal amplifier [11, 92]. The resulting elevation in intracellular Ca²⁺ concentrations further activates calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2 (CaMKK2) [93]. CaMKK2 phosphorylates downstream effectors including AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and AKT, ultimately promoting STAT6 nuclear translocation and M2-associated gene transcription [89]. Intriguingly, Xie et al. revealed in a PDAC model that elevated matrix stiffness cooperatively activates both Piezo1-mediated Ca²⁺ influx and the integrin β1-filamentous actin signaling axis, which together induce phosphorylation of the proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2) in the cytoplasm. Activated PYK2 not only amplifies mechanical signals by modulating cytoskeletal reorganization but also translocates into the nucleus, where it directly binds to the promoter regions of genes such as v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A and subunits of the Arp2/3 complex, driving their transcription and thereby promoting monocyte differentiation into M2-like macrophages [11].

Mechanisms by which elevated matrix stiffness modulates macrophage polarization and immunoregulatory functions. Increased stiffness transmits signals via the integrin β5-cytoskeleton axis to enhance chromatin accessibility at M2 gene promoter regions, initiating M2-polarizing transcriptional programs. In hepatocellular carcinoma, stiffness promotes M2 polarization through the integrin β5-focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 and 2 (MEK1/2)-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2)-hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α (HIF-1α)-lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2) signaling cascade. Concurrently, activation of mechanosensitive channels Piezo1 and TRPV4 induces Ca²⁺ influx, leading to Ca²⁺/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 2 (CaMKK2) activation and subsequent STAT6 nuclear translocation. In a complementary pathway, Piezo1-mediated Ca²⁺ signaling synergizes with the integrin β1-F-actin axis to activate proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2), which translocates to the nucleus and binds promoters of RELA and Arp2/3 complex subunits (e.g., ACTR3), further promoting M2 differentiation. Furthermore, stiffness-induced M2-like TAMs upregulate heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2 (HSPG2), whose aberrant deposition creates a positive feedback loop that further elevates matrix stiffness. Additionally, high stiffness stimulates TAMs to secrete pro-tumor factors (e.g., TIMP-1, CCL7), induces autocrine transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-SMAD signaling to promote collagen synthesis, and drives metabolic reprogramming via the TGF-β-arginase-1 axis, resulting in arginine depletion and ornithine accumulation that collectively impair CD8⁺ T cell function.

However, current research findings regarding the relationship between matrix stiffness and macrophage polarization remain conflicting [94, 95], primarily due to technical variations in experimental systems and the inherent biological complexity of the TME. Specifically, many investigations rely on 2D substrates, which fail to recapitulate the architectural and mechanical complexity of native tumor ECM. Furthermore, the definition of "stiffness" varies considerably across studies, lacking standardized quantitative ranges. Substantial differences in cellular models—ranging from transformed cell lines such as THP-1 human monocytes to primary bone marrow-derived macrophages—also contribute to divergent mechanoresponsive behaviors and polarization outcomes [89].

Taken together, matrix stiffness biases macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype through multiple mechanosignaling pathways and synergistic interactions with biochemical signals. The polarized M2 macrophages subsequently establish an immunosuppressive microenvironment by secreting inhibitory cytokines, impairing the function of effector T cells and NK cells, and recruiting immunosuppressive cells such as Tregs. Collectively, these mechanisms promote immune evasion and tumor growth [86].

2.1.2 Matrix stiffness promotes the migration and infiltration of M2-like TAMs

The spatial distribution of macrophage subsets within the TME is influenced by their phenotype-specific migratory and adhesive behaviors. Elevated matrix stiffness modulates the expression of adhesion- and migration-related molecules in TAMs, potentially favoring the infiltration of M2-like TAMs into stiffer matrix regions [12, 42, 96, 97]. This provides a plausible mechanistic explanation for the positive correlation between increased matrix stiffness and a higher proportion of M2-like TAMs observed in solid tumors such as head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [36, 88]. Such stiffness-guided migration enables M2-like TAMs to penetrate deeply into tumor parenchyma, engage in close interactions with cancer cells, and amplify their immunosuppressive functions [42].

Integrin-mediated adhesion represents a core mechanism governing the 3D migration of macrophages, a process highly dependent on integrin expression levels [97]. Within the TME, elevated matrix stiffness acts as a critical biomechanical cue that coordinates integrin-dependent migration by regulating integrin activation, adhesion complex dynamics, cytoskeletal reorganization, and downstream signaling pathways, thereby determining migratory mode and efficiency [96]. Compared to M1-like TAMs, M2-like TAMs exhibit higher expression of integrin β5 [12] and β3 [98]. Both integrins recognize the RGD motif and synergy sites within fibronectin—a component enriched in stiffened tumor stroma [6, 14]—and couple extracellular adhesion to intracellular mechanical functions via linkage to the actin cytoskeleton through cytoplasmic adaptor proteins [99]. Increased matrix stiffness facilitates force transmission, promoting the maturation of nascent adhesions into focal adhesions and fibrillar adhesions. Integrins, particularly αvβ3, exhibit enhanced activation in stiffer regions, leading to recruitment of talin and paxillin, which stabilize adhesion complexes and direct durotactic migration [96]. Notably, high stiffness upregulates integrin β5 expression in M2-like TAMs [12], further promoting their mechanotactic migration [96]. Concurrently, elevated tumor stiffness enhances the secretion of MMPs in M2-like TAMs [100]. MMPs not only degrade ECM components [31] but also cleave fibronectin to expose cryptic RGD sites, thereby amplifying matrix remodeling and invasive capacity [96]. Together, these mechanisms drive the preferential accumulation of M2-like TAMs in stiffened areas of the tumor ECM, where their abundance correlates positively with matrix stiffness [42], thereby facilitating immunosuppression and promoting tumor immune evasion.

2.1.3 Matrix stiffness enhances TAM-mediated immunosuppression

Matrix stiffness not only directly polarizes macrophages toward the immunosuppressive M2 phenotype but also augments their protumor factor secretion and exacerbates metabolic dysregulation in the TME, collectively impairing antitumor T cell responses [57, 101]. Clinical analyses reveal that elevated matrix stiffness in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma correlates with upregulated secretion of pro-tumor factors (e.g., TIMP-1, C-C motif chemokine ligand 7, and angiopoietinrelated protein 3) by M2-like TAMs [36, 88]. What's more, in metastatic ovarian cancer, elastic moduli can be 100-fold higher than in healthy omentum; such stiff matrices induce M2-like TAMs to overexpress TGFBI, suppressing CD8+ T cell function [101].

Macrophages infiltrating the high-stiffness TME exhibit enhanced immunosuppressive activity. Their conditioned medium directly suppresses T-cell proliferation and impairs the secretion of effector molecules such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) [36, 102], while autocrine activation of the TGF-β signaling pathway exacerbates metabolic dysregulation in the BC TME [57]. For example, in BC models, matrix stiffness remodels TAM function through a dual mechanism: on one hand, it induces autocrine TGF-β release from TAMs, activating the TGF-β/SMAD pathway to promote collagen synthesis; on the other hand, it drives metabolic reprogramming via the TGF-β-arginase-1 axis, enhancing arginine uptake and proline synthesis. This leads to excessive ornithine production and release into the TME, resulting in arginine depletion and ornithine accumulation [57]. Arginine depletion impairs adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis and effector molecule production in T cells [103], while ornithine competitively inhibits solute carrier family 7 member A transporter-mediated arginine uptake, disrupting metabolic homeostasis in T cells—manifested as elevated oxidized glutathione and reduced ATP levels. These changes collectively inhibit CD8⁺ T-cell proliferation, activation, and tumor-killing capacity, and diminish their response to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy [57].

In aggregate, these findings elucidate the mechanobiological mechanisms by which stiffness amplifies TAM-driven immunosuppression to facilitate immune evasion. The following section details stiffness-mediated biomechanical regulation of T cell function.

2.2 Matrix stiffness suppresses T cell activation, migration, and cytotoxic function

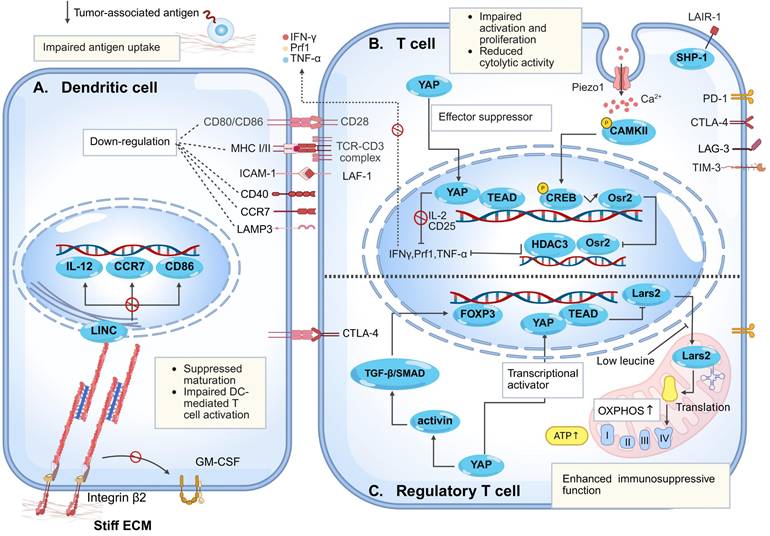

An effective anti-tumor immune response relies on the complete activation and cascade amplification of the "cancer-immunity cycle." During this process, DCs initiate T cell responses by presenting tumor antigens via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Ⅰ/Ⅱ, followed by activated effector T cells migration to tumor sites for recognition and killing of tumor cells [104]. Nonetheless, abnormally elevated matrix stiffness in tumor tissues prevents effective activation of this cycle. Acting as a regulator of adaptive immune cell behavior, high matrix stiffness suppresses T cells activation and proliferation, impairs their migratory capacity, and reduces tumor infiltration efficiency. More importantly, high matrix stiffness induces T cell exhaustion, significantly impairs their effector functions [35, 37, 105], and ultimately leads to tumor immune evasion and triggers clinical treatment resistance (Fig. 4).

2.2.1 Matrix stiffness inhibits T cell activation and proliferation

Elevated matrix stiffness suppresses T cell activation and proliferation through multiple mechanisms, including disruption of immune synapse (IS) formation and regulation of the YAP signaling pathway [105, 106]. IS formation represents a critical step in T cell activation, with its structure centered on the T cell receptor (TCR)-MHC-peptide complex, surrounded by adhesion molecules to form a "bullseye" architecture [107]. Within the physiological stiffness range (approximately 5-20 kPa), the counterforce provided by the matrix enables TCR-pMHC bonds to sustain and maintain appropriate levels of tension, thereby stabilizing microclusters, prolonging their lifetime, and amplifying downstream signaling. Conversely, excessively high matrix stiffness may impose supraphysiological tension, leading to premature bond dissociation and disruption of microcluster stability—unless compensatory mechanical support is provided by integrins such as lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 to preserve synaptic structure and function [108, 109]. Consistent with this, Jin et al. utilized elastic micropillar arrays to demonstrate that elevated substrate stiffness delays the translocation of the microtubule-organizing center to the IS, ultimately impairing synapse formation and T-cell activation [106].

In addition to synaptic regulation, studies utilizing 3D collagen-based matrices that mimic the features of solid tumor ECM have revealed that high matrix stiffness activates mechanosensing pathways, leading to YAP nuclear translocation and complex formation with TEA domain transcription factor (TEAD). This suppresses the expression of T-cell activation-related genes (e.g., IL-2, CD25) and impairs their proliferative capacity [105]. Furthermore, investigations based on 3D in vitro models have shown that under high-stiffness conditions, CD8⁺ T-cell viability is more susceptible to impairment than that of CD4⁺ T cells, resulting in an altered CD4⁺/CD8⁺ ratio and reduced cytotoxic output [39]. Importantly, T-cell proliferation exhibits a biphasic response to substrate stiffness, with the highest fold increase in cell numbers observed on 25 kPa PA gels [110]. This may be attributed to the release of YAP from the cytoplasm and its subsequent nuclear import, which prevents its binding to IQ motif-containing GTPase-activating protein 1, thereby permitting nuclear translocation of nuclear factor of activated T-cells 1 and enhancing glycolytic and amino acid metabolic pathways in T cells to support proliferation [111]. However, as stiffness increases beyond this point, T-cell proliferation demonstrates a declining trend [110].

Mechanism of high matrix stiffness in regulating dendritic cells, T cells, and regulatory T cells. (A) Elevated matrix stiffness impairs DCs antigen capture capacity by reducing tumor immunogenicity and creating a physical barrier. Simultaneously, increased stiffness reinforces integrin β2-cytoskeleton linkage, leading to negative regulation of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) signaling and triggering Lamin A/C-mediated chromatin condensation. This directly suppresses the transcription of maturation-related genes, including CD86, interleukin-12 (IL-12), and CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7), resulting in arrested DC maturation. Furthermore, via β2 integrin signaling, high stiffness downregulates the expression of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80/CD86) and CCR7 on mature DCs, thereby further inhibiting T cell activation. (B) Within T cell-related regulatory mechanisms, elevated matrix stiffness promotes nuclear translocation of Yes-associated protein (YAP), which forms a complex with TEA domain transcription factor (TEAD) to suppress the expression of T cell activation-related genes (e.g., IL-2, CD25) and impair proliferative capacity. Concurrently, it downregulates the expression of effector molecules such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), thereby inhibiting CD8⁺ T cell cytotoxicity. On the other hand, high stiffness upregulates the expression of leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor 1 (LAIR1), which recruits Src homology 2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) and contributes to T cell exhaustion. Additionally, Piezo1 activation via the Ca²⁺-calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase Ⅱ (CaMKⅡ)-cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) axis upregulates odd-skipped related transcription factor 2 (Osr2), which recruits histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) to reduce cytotoxic gene histone acetylation, suppressing T cell function. (C) Elevated stiffness drives regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation/maintenance via dual YAP mechanisms: enhancing mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and activating transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/SMAD-forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) signaling. These processes reinforce Treg immunosuppression, facilitating tumor immune evasion.

It should be noted that most current studies are conducted on planar surfaces, whereas cell-matrix interfaces exhibit more complex spatial topologies; thus, some conclusions may differ from those derived from planar gel systems [106]. Collectively, elevated matrix stiffness disrupts immune synapse formation, inhibits YAP/TEAD-dependent transcriptional activation, and ultimately causes defects in T-cell activation and proliferation. These effects compromise both the initial recognition of tumor antigens and the expansion of immune responses, thereby collectively impairing the anti-tumor functionality of T cells.

2.2.2 Matrix stiffness restricts T cell infiltration and migration

Effective immune surveillance requires the precise localization and motility of T cells within tumors. For cytotoxic function, infiltrating T cells must navigate between and interact with tumor cells [112].

Nonetheless, in many tumor types, the desmoplastic reaction occurring in the TME is directly associated with increased matrix stiffness [22] and leads to the formation of dense connective tissue that encapsulates tumor nests [21, 27, 113]. The infiltration and migratory capacity of T cells are severely impaired due to physical confinement [21, 114]. Consequently, T cells are sparsely distributed within tumor nests and are instead predominantly enriched in the surrounding stromal regions [115]. This restricted spatial distribution and heterogeneous clustering represent a key mechanism of immune evasion. Significantly, reducing matrix stiffness through collagenase treatment has been shown to enhance T cell-tumor cell contact and thereby improve anti-tumor immune responses [114-116].

Unlike adherent cells, T lymphocytes do not form substantial attachments to the ECM, instead transmitting frictional forces through retrograde flow of the actin cytoskeleton. This enables them to employ conserved migratory strategies across tissues with vastly different compositions [117]. Consequently, matrix barriers exhibit comparable inhibitory effects on T cell migration across diverse tumor types. In ovarian and lung cancer tissues, T cells primarily accumulate in stromal regions and display marked migratory slowness [114, 115]. In PADC, collagen-rich stroma traps infiltrating T cells, with activated T cells migrating efficiently in low-density collagen but suppressed in high-density environments [118]. Mechanistic studies reveal that in loose fibronectin/collagen regions, T cells undergo rapid β1/β2-integrin-independent migration via chemokine receptor-mediated chemotaxis. Conversely, in dense matrices, single-cell migration capacity inversely correlates with collagen density and stiffness, culminating in peripheral trapping and failed infiltration [23].

Intriguingly, studies utilizing polyethylene glycol-fibrinogen hydrogels to mimic the stiffness of breast tumors have demonstrated that elevated matrix stiffness can also induce nuclear enlargement in T cells through membrane mechanocompression, thereby impairing their infiltrative capacity [39]. This multifactorial regulatory network ultimately dictates T-cell distribution and functional states within tumors, thereby determining overall antitumor immune efficacy [116].

2.2.3 Matrix stiffness suppresses T cell-mediated immune killing

Besides acting as a physical barrier, elevated matrix stiffness reshapes T cell function across multiple dimensions—including receptor signaling [119], ion channels [120], and transcriptional regulation [121, 122]—through activation of multiple mechanosensitive pathways. This process induces T cell exhaustion, suppresses cytotoxic activity, and ultimately constitutes the core mechanical regulatory network driving tumor immune evasion [39, 40]. In tumors with abundant collagen deposition (e.g., lung cancer), expression of the collagen receptor leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1 (LAIR1) is significantly upregulated. LAIR1 recruits Src homology 2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) via its intracellular domain, directly inducing T cell exhaustion and rendering programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade therapy ineffective [119].

Concomitantly, activation of the Piezo1 in T cells represents another critical regulatory axis. Specifically, Piezo1 is highly expressed in activated CD8⁺ T cells and functions as a negative regulator of cytotoxicity. Inhibition of Piezo1 activity enhances T-cell traction forces and augments their tumor-killing capacity [120]. Nonetheless, under conditions of high tumor matrix stiffness, Piezo1 activation upregulates odd-skipped related transcription factor 2 (Osr2) through the Ca²⁺-Ca²⁺/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase Ⅱ-cAMP response element-binding protein axis. Osr2 recruits histone deacetylase 3 to suppress cytotoxic gene transcription, impairing T cells function. Osr2 deletion reduces exhaustion, enhances antitumor responses, and improves chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy (CAR-T) efficacy in solid tumors [37]. Furthermore, in vitro models have confirmed that elevated matrix stiffness promotes nuclear translocation of YAP in effector T cells [111, 123]. As a suppressor of T cells effector responses, enhanced YAP transcriptional activity directly impairs the cytotoxic function of CD8⁺ T cells, manifesting as downregulated expression of effector molecules such as IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [105, 121].

Significantly, in many cancers, tumor-intrinsic alterations preferentially recruit and activate Tregs rather than effector T cells [124, 125]. Accumulation of immunosuppressive Tregs is a key immune evasion strategy [126]. Unlike immune effector cells, elevated matrix stiffness within tumors promotes cancer immune evasion by activating the mechanosensitive protein YAP, which induces the differentiation of Tregs, enhances their oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) metabolism, and strengthens their immunosuppressive functions [122, 127, 128].

A 2D study utilizing PA hydrogels demonstrated that the differentiation efficiency of human CD4⁺CD25⁺ T cells into Tregs correlates positively with matrix Young's modulus, and Tregs display significant upregulation of mitochondrial genes associated with OXPHOS [127]. Elevated OXPHOS rates not only facilitate Tregs induction but also sustain their anti-inflammatory phenotype and suppressive function [129]. Mechanistically, employing both in vivo and in vitro tumor models, Ni et al. demonstrated that matrix stiffness-activated YAP plays a central regulatory role in the differentiation and functional maintenance of tumor-infiltrating Tregs (TI-Tregs) [122]. On one hand, YAP enhances mitochondrial OXPHOS efficiency by upregulating mitochondrial leucyl-tRNA synthetase 2, providing metabolic support for TI-Tregs function maintenance [122]; on the other hand, YAP amplifies TGF-β/SMAD activation in TI-Tregs by activating key signaling components of the activin receptor complex, inducing forkhead box protein P3 (FOXP3) expression and reinforcing TI-Tregs immunosuppressive function [122, 130]. Clinical analyses confirm that infiltration of YAP-high TI-Tregs correlates significantly with poor prognosis in gastric cancer patients [122]. In colorectal cancer and melanoma models, elevated matrix stiffness regulates the differentiation and functional maintenance of Tregs through mechanosensitive signaling axes [122]. Conversely, reduced YAP activity results in a decreased proportion of FOXP3⁺ Tregs, diminished expression of immunosuppressive molecules, and impaired Treg-mediated immunosuppression, indicating that targeting YAP may overcome Treg-mediated immunotherapy resistance [122, 130].

2.3 Matrix stiffness impairs dendritic cell antigen presentation

DCs play a critical role in antigen presentation and triggering in vivo immune responses [131]. Immature DCs (iDCs) efficiently recognize and internalize tumor-associated antigens. Upon antigen stimulation, iDCs differentiate into mature DCs (mDCs), characterized by actin cytoskeleton remodeling [132], enhanced migratory capacity, and upregulated expression of MHC molecules and costimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD86 and CD83. These features facilitate antigen presentation and T cells activation, thereby potentiating local anti-tumor immunity [131, 133]. However, as a key environmental factor regulating DCs maturation and anti-tumor function, pathologically elevated matrix stiffness not only reduces the number of intratumoral mDCs and impairs their migratory capacity but also disrupts antigen processing and presentation cascades, systematically undermining DCs immunosurveillance. This ultimately attenuates T cell responses and promotes immune evasion [9, 40, 133].

2.3.1 Matrix stiffness suppresses DC antigen uptake and maturation

Matrix stiffness plays a pivotal role in tumor immune evasion by disrupting the initiation of subsequent anti-tumor immune responses through its effects on DC antigen uptake and maturation processes [9, 40, 133]. During the antigen recognition and uptake phase, iDCs rely on integrin-mediated dynamic assembly of focal adhesions and podosome extension to monitor the immunogenic microenvironment [134]. Elevated stiffness, nevertheless, suppresses tumor immunogenicity by activating the Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase-non-muscle myosin heavy chain ⅡA-filamentous actin pathway in tumor cells, which inhibits cGAS-STING pathway activation and consequently reduces DC differentiation [9]. Simultaneously, the physical barrier imposed by stiff matrices limits spatial encounters between iDCs and antigens [40, 135], fundamentally impairing the transition from iDCs to immunocompetent mDCs [9, 40].

Additionally, DCs maturation involves cytoskeletal remodeling and increased cortical stiffness [132], enabling the transition from podosome-rich to amoeboid-like high-velocity migratory phenotypes via podosome disassembly [134], which facilitates lymph node homing. Notably, Morrison et al. identified β2 integrin as a negative regulator of DCs maturation, suppressing the mature phenotype by maintaining cytoskeletal linkages and restricting granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimula-ting factor receptor signaling [136]. In integrin ligand-coated hydrogel models, elevated matrix stiffness enhances integrin β2-actin mechanical coupling and triggers Lamin A/C-mediated chromatin condensation, which directly suppresses the transcriptional activation of maturation-related genes such as CD86, IL-12, and CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7). Consistent with this, DCs with impaired β2 integrin function exhibit a markedly enhanced maturation profile in melanoma models [133]. Consequently, DCs retained within stiff microenvironments undergo maturation arrest, characterized by persistent podosomes that impede the acquisition of an amoeboid migratory phenotype and full immune response activation [134]. Jointly, high matrix stiffness-induced dysfunction of DCs facilitates the evasion of immune recognition by tumor cells, thereby promoting tumor immune evasion.

2.3.2 Matrix stiffness impairs DC-mediated T cell activation

Matrix stiffness impairs DC-mediated T cell activation by downregulating surface costimulatory molecules and CCR7 expression on mDCs [133, 137]. β2-integrins play a critical role in restricting DC-dependent T cell activation—a perspective inversely validated in studies by Guenther et al. [136]. Soft substrates (0.87 kPa PA gels), by reducing integrin-mediated mechanical stress, mimic integrin inactivation. Inactive β2 integrins enhance DCs migratory capacity and IL-12 secretion, specifically upregulating expression of costimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80, CD86) and chemokine receptor CCR7 on bone marrow-derived DCs, thereby significantly promoting CD8⁺ T cell infiltration and melanoma suppression [133]. Furthermore, in lung adenocarcinoma, the transcription factor SRY-box transcription factor 9 exacerbates tumor matrix stiffening by promoting collagen synthesis, inducing functional impairment of DCs. This manifests as aberrant expression of surface markers including CD103, CD80, CD86, and lysosome-associated membrane protein 3. Such functionally compromised DCs trigger exhausted differentiation of CD8⁺ T cells in the TME, characterized by upregulated lymphocyte activation gene 3 and downregulated Ki67 [40], ultimately impairing anti-tumor responses.

Collectively, as a key regulator of DC-mediated immunosuppression, matrix stiffness drives pathological immune evasion through synergistic integrin-dependent mechanosensing defects and transcriptional dysregulation.

2.4 Matrix stiffness suppresses NK cell migration and cytotoxic function

As key effectors of innate immunity, NK cells can detect and destroy cancer cells without the need for tumor-specific recognition or MHC restriction. This mechanism contrasts with that of T cells and endows NK cells with broader antitumor potential [138]. This unique biology establishes NK cells as vital components of tumor immunosurveillance [139].

Nevertheless, pathologically elevated matrix stiffness in the TME significantly impairs NK cells cytotoxic activity through synergistic physical constraints and molecular signaling, promoting tumor immune evasion [4, 40]. In lung adenocarcinoma, SRY-box transcription factor 9-mediated matrix stiffening correlates significantly with downregulated expression of NK cells functional markers (e.g., granulysin, killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily D member 1), indicating compromised cytotoxic function [40]. This observation is further corroborated in luminal BC: upregulated signal peptide-CUB-EGF domain-containing protein 2 promotes collagen deposition through osteoblast-like differentiation. Collagen fibers—structural determinants of stiffness—are specifically recognized by LAIR1, an inhibitory receptor highly expressed on NK cells. LAIR1-collagen binding triggers SHP-1 phosphorylation cascades that suppress transcriptional expression of effector molecules (IFN-γ, TNF-α) [140].

Furthermore, the activation and effector functions of NK cells require substantial metabolic support from glucose and amino acids such as glutamine and arginine [141]. However, in BC, elevated matrix stiffness reprograms the metabolism of TAMs, leading to arginine depletion in the TME [57]. This metabolic alteration disrupts glycolytic flux and may induce mitochondrial dysfunction in NK cells, ultimately impairing their cytotoxic activity [141]. Through these mechanisms, high tumor matrix stiffness significantly dampens NK cells cytotoxicity and immune reactivity, thereby reducing the efficiency of immune surveillance.

2.5 Matrix stiffness promotes neutrophil N2 polarization and NETs formation

Neutrophils and their NETs are key players in tumor immune regulation [65]. Analogous to macrophage plasticity, TANs exhibit environment-dependent phenotypic differentiation: anti-tumor N1-TANs are characterized by high expression of interferon-γ-inducible protein 10/TNF-α and production of reactive oxygen species, whereas pro-tumor N2-TANs upregulate CD206 and CXCL12, secrete higher levels of IL-10, and drive immunosuppression by inhibiting T cell activation and upregulating immune checkpoint molecules [142]. Moreover, NETs can form a physical barrier that isolates tumor cells from immune attack and captures circulating tumor cells, thereby promoting immune evasion and diminishing the efficacy of immunotherapy [65, 143]. In vitro hydrogel models have demonstrated that increased matrix stiffness drives neutrophil N2 polarization and NET formation [144, 145].

Jiang et al. demonstrated, using methacrylated gelatin hydrogels that partially recapitulate TME stiffness, that increased matrix stiffness drives neutrophil polarization toward an N2 phenotype via activation of the JAK1/STAT3 mechanotransduction pathway [144]. Supporting the relevance of this pathway in tumors, Ozel et al. identified STAT3 signaling as a critical regulator of TANs N2 polarization in tumor models, observing that STAT3 knockout significantly suppresses NETs formation while enhancing cytotoxic CD8⁺ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity [146]. These findings suggest that elevated tumor matrix stiffness may promote immune evasion by regulating N2 polarization and NETosis in neutrophils. Furthermore, Abaricia et al. revealed, using polydimethylsiloxane substrates of varying stiffness, that matrix hardness enhances NET formation in a stiffness-dependent manner through integrin/FAK signaling. Although not yet validated in tumor models, this mechanism implies that high stiffness in the tumor stroma may similarly activate neutrophils via the integrin/FAK axis to induce NET formation [145]. Collectively, while current evidence—primarily derived from non-tumor models—indicates that matrix stiffness likely influences neutrophil polarization and NET release through multiple mechanisms, further validation in tumor-specific contexts remains essential for future research.

2.6 Matrix stiffness modulates other immune cell populations

Beyond the immune cells previously discussed, the influence of matrix stiffness on other immune populations—such as monocytes and B cells—should not be overlooked. Within the TME, monocytes exhibit dual roles, exerting both anti-tumor effects through the production of anti-tumor effector molecules and activation of antigen-presenting cells [147], as well as pro-tumor functions. Elevated matrix stiffness can skew monocyte function toward a pro-tumor phenotype. For instance, in PDAC, increased matrix stiffness promotes the differentiation of monocytes into M2-like TAMs [11]. Furthermore, under 3D high-stiffness conditions, co-culture of estrogen receptor-positive BC cells with monocytes resulted in enhanced monocyte-tumor cell adhesion and increased secretion of pro-tumor proteins, collectively driving the TME toward a tumor-promoting state [148].

B cells enhance anti-tumor immune responses through the production of tumor-specific antibodies, antigen presentation to T cells, and secretion of immunomodulatory molecules. TLS serve as critical hubs within the TME for B cell activation, class switching, and maturation, which are essential for their anti-tumor functions [149]. Within TLS, B cells undergo clonal expansion and antibody class switching, leading to the production of high-affinity immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA antibodies [150]. These antibodies not only directly mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and phagocytosis via Fc receptors on macrophages and NK cells but also form immune complexes that enhance antigen presentation by DCs, thereby amplifying T cell responses and promoting epitope spreading. Additionally, TLS facilitates bidirectional crosstalk between B and T cells, which is critical for sustaining germinal center reactions and plasma cell differentiation [149].

Research indicates that changes in matrix stiffness may have a significant impact on B cell function within the TME. Elevated stiffness has been shown not only to suppress the formation of TLS [24] but also to exert differential regulation on B-cell activation, proliferation, and class-switch recombination [151, 152]. Studies by Zeng et al. revealed that rigid polydimethylsiloxane substrates enhance the initial phase of B-cell activation by promoting B-cell receptor microcluster formation and recruitment of phosphorylated spleen tyrosine kinase to the immunological synapse, whereas softer substrates preferentially support subsequent clonal expansion, IgM-to-IgG1 class switching, and potent antibody responses in vivo [151]. Observations in patient-derived breast tumor explant cultures further support the stiffness-dependent promotion of B-cell activation, as soft matrix conditions resulted in a significant reduction in B-cell abundance within the TME [152]. We propose that this "double-edged sword" effect reflects an adaptive physiological mechanism, enabling B cells to fine-tune their functional output in response to biomechanical cues to balance rapid infection control against the establishment of antibody diversity and immunological memory [151]. During tumor progression, however, persistently elevated stiffness may disrupt this homeostatic balance—not only by impairing TLS assembly [24] but also by skewing B-cell differentiation toward abortive activation, thereby compromising sustained antibody production, inhibiting B-cell recruitment into TLS, and ultimately undermining antitumor immunity.

To summarize, while the role of elevated tumor matrix stiffness in promoting immune evasion through the regulation of immune cells—such as macrophages, T cells, and DCs—has been increasingly elucidated, its specific effects on fundamental cellular behaviors, including activation, proliferation, migration, and secretion, remain highly context-dependent. Owing to substantial variations in substrate materials and culture conditions used across experimental systems, stiffness-induced immunomodulation exhibits considerable heterogeneity, underscoring the complexity of mechanical regulation within the TME. Therefore, there is an urgent need to investigate the spatiotemporal dynamics of matrix stiffness and its regulatory impact on anti-tumor immunity using in vivo models and clinical samples.

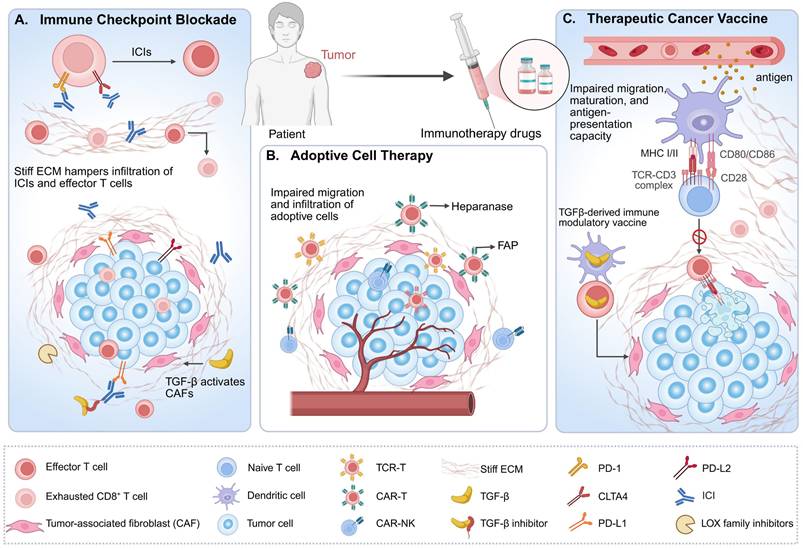

3. Matrix Stiffness Creates a Therapeutic Desert for Immunotherapy

Differing from conventional chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapies, immunotherapy operates by "awakening" or "arming" the host immune system to specifically recognize and eliminate tumor cells [153]. Despite its substantial therapeutic potential, however, immunotherapy continues to confront significant challenges. Emerging evidence increasingly underscores the critical role of biophysical factors within the TME [4, 154]. Among these, elevated matrix stiffness not only establishes physical barriers that hinder the infiltration of immune cells such as T cells, NK cells, and DCs, but also, through modulation of immune cell activation and function, concurrently restricts the transport and penetration of immunotherapeutic agents [7, 155]. In aggregate, these effects compromise the efficacy of diverse immunotherapeutic modalities—including ICB, adoptive cell therapy (ACT), and therapeutic cancer vaccines—ultimately impacting clinical treatment outcomes [41, 43].

Significantly, research combining matrix-targeting strategies with immunotherapy is rapidly emerging. Accumulating preclinical evidence consistently indicates that such combinatorial approaches hold promise for enhancing therapeutic efficacy [156-158]. However, despite the considerable promise shown by stroma-directed strategies in preclinical models, their clinical translation is complicated by the inherent heterogeneity of ECM components and the critical role of physiological matrix remodeling in normal tissue repair. These factors pose significant challenges to the specificity and safety profiles of such interventions, increasing the risks of off-target effects and unintended toxicity [116]. Therefore, there is a pressing need for more rigorously designed studies to evaluate these combination therapies in physiologically and clinically relevant contexts (Fig. 5).

3.1 Immune checkpoint blockade therapy

As a cornerstone of cancer immunotherapy, ICB reactivates the anti-tumor immune function of T cells by blocking immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1/PD-L1, and has emerged as a landmark breakthrough in cancer immunotherapy. Nonetheless, clinical data indicate that only a subset of patients derive benefit from this approach. The mechanisms underlying ICB resistance are multifaceted, with therapeutic responses closely associated with the phenotype of CD8+ effector T cells [2]. Recent studies have revealed that elevated tumor matrix stiffness not only amplifies cancer immune evasion by upregulating the expression of immune checkpoint molecules PD-L1, PD-1, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) [43, 159], but also forms physical barriers that impede T cell migration and infiltration [21, 114], while limiting the delivery and penetration of immune checkpoint inhibitors [155]. Additionally, it directly exacerbates CD8+ T cells exhaustion and downregulates their cytotoxicity via mechanotransduction pathways [37], synergistically contributing to ICB treatment failure. For instance, partial non-response to anti-CTLA-4 therapy stems from collagen deposition-induced reductions in T cells tumor infiltration [160]. Recent investigations have further demonstrated that matrix stiffness can induce PD-L2 expression and impair the efficacy of sorafenib combined with anti-PD-1 therapy in treating HCC in vivo [161].

In response, a growing body of preclinical evidence supports the combination of matrix stiffness-targeting agents with ICB [156, 162]. For example, a nanoscale remodeler (SPNcb) that integrates photodynamic therapy with tumor-specific LOX inhibition enables activatable cancer photoimmunotherapy. By reducing matrix stiffness, it enhances drug penetration and immune cell infiltration, and when combined with anti-PD-L1 checkpoint blockade, significantly improves antitumor efficacy [155]. Similarly, TGF-β targeting suppresses TGF-β signaling in CAFs and reduces ECM deposition, thereby alleviating both physical and immunosuppressive barriers to T-cell infiltration in the TME. This approach synergizes with PD-L1 inhibition to enhance antitumor immune responses in BC models [162].

These findings suggest that targeted modulation of matrix stiffness to improve T cells function may emerge as a novel strategy to overcome ICB resistance, underscoring the critical clinical translational value of elucidating the interplay between matrix mechanical properties and immunotherapy.

3.2 Adoptive cell therapy

ACT represents a primary modality of cancer cell-based treatment. Its core mechanism involves extracting immune cells from patients, enhancing their anti-cancer capabilities through genetic modification or ex vivo expansion, and re-infusing them into the patient. Major ACT subtypes include CAR-T therapy, T cell receptor-engineered T-cell therapy, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes therapy, and NK cell therapy [163]. Nonetheless, the efficacy of ACT is highly dependent on the infiltration capacity, persistence, and functional maintenance of immune effector cells within the TME—key processes that are significantly regulated by matrix stiffness [41, 157].

Studies have demonstrated that increased matrix stiffness not only impedes tumor penetration by T cells and NK cells while dampening their anti-tumor responses [39, 40], but also severely restricts the migration and infiltration efficiency of adoptively transferred cells within the TME, emerging as a primary bottleneck in ACT for solid tumor treatment [157, 164]. For instance, physical barriers formed by the tumor ECM hinder the migration of CAR-T cells to target sites, thereby reducing their clinical efficacy [157, 164].

To address this challenge, modulating TME mechanical properties to enhance adoptive cell infiltration and anti-tumor immune function has emerged as a breakthrough strategy [164, 165]. Recent studies, using a human BC MDA-MB-231 xenograft model, have demonstrated that intratumoral pretreatment with nattokinase effectively reduces matrix stiffness, significantly enhances CAR-T cells tumor infiltration, and potentiates their tumor-suppressive effects—offering novel insights for improving the clinical efficacy of ACT [165]. In addition to enzymatic approaches, alternative strategies—such as engineering CAR-T cells to express heparanase—enhance their capacity to degrade the ECM, thereby facilitating T-cell infiltration and augmenting anti-tumor activity [164]. Furthermore, combining thermally inducible CAR-T cells with hyperthermia regimens mitigates the desmoplastic characteristics of stiff TMEs and improves T-cell penetration through the ECM, ultimately enhancing the efficacy of CAR-T cell therapy in glioblastoma [157].

These ongoing explorations provide valuable insights into targeting the tumor ECM to optimize ACT, highlighting a dynamic and rapidly evolving research landscape with significant implications for developing more effective cancer immunotherapies.

3.3 Therapeutic cancer vaccines

Fundamental principles governing successful therapeutic cancer vaccination encompass the delivery of high-quality antigens to DCs in substantial quantities, optimal DCs activation, induction of robust and sustained CD4+ T helper cell and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses, as well as the persistence of TME infiltration and reactivity [166]. Nevertheless, elevated matrix stiffness disrupts this immunological cascade through multifaceted mechanisms: it not only impedes DCs tumor infiltration and maturation processes but also significantly impairs their antigen presentation capacity, ultimately resulting in inadequate T cells activation and defective anti-tumor immune responses [137, 167]. These effects severely limit the efficacy of therapeutic cancer vaccines.

Elevated matrix stiffness impairs cancer immunotherapy efficacy. (A) Elevated matrix stiffness not only physically impedes the delivery of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) to exhausted CD8⁺ T cells and deep tumor nests, but may also directly impair the cytotoxic capacity of reinvigorated T cells and promote their re-exhaustion through mechanotransduction signaling. Combining ICIs with inhibitors targeting TGF-β and lysyl oxidase (LOX) family enzymes has emerged as an effective strategy to restore anti-tumor responses. (B) This physical barrier similarly hinders the infiltration of adoptive cell therapies (ACTs)—including chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T), T cell receptor-engineered T cells (TCR-T), and CAR-natural killer (NK) cells—compromising their therapeutic efficacy. Engineering approaches, such as CAR-T cells expressing heparanase or targeting fibroblast activation protein (FAP), have shown promising results in preclinical models by enhancing stromal penetration and specifically targeting stromal cells. (C) Elevated matrix stiffness critically impairs the efficacy of therapeutic cancer vaccines by disrupting dendritic cell infiltration, compromising their maturation, and ultimately attenuating their antigen-presenting capacity. Although vaccines can activate and expand antigen-specific T cells capable of recognizing MHC-presented antigens and infiltrating tumors, impaired antigen presentation ultimately attenuates vaccine efficacy. Innovative strategies such as TGF-β vaccines, which enable T cells to directly target cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), offer a novel immunotherapeutic approach.

To overcome these barriers, innovative strategies continue to emerge. Hu et al. combined a tumor nanovaccine with a sperm adhesion molecule 1-mediated ECM-clearing agent, which promoted immune cell infiltration and achieved potent antitumor efficacy in B16-OVA tumor-bearing mice [158]. Similarly, Perez-Penco et al. developed a TGF-β vaccine that reduces immunosuppressive M2-like TAMs and myofibroblastic CAFs, thereby alleviating immune exclusion and matrix stiffness in the pancreatic cancer TME. This approach has shown promise in preclinical models and is currently under evaluation in a Phase Ⅰ clinical trial (EudraCT No. 2022-002734-13) [168]. These advances underscore the promising potential of targeting stromal biomechanics to enhance the efficacy of tumor vaccines and restore antitumor immunity.

4. Matrix Stiffness-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies